Готовая программа не всегда работает как надо. Бывает, возникают баги, предупреждения, исключения. В итоге программа зависает, дает сбой или вылетает. Но это не конец света. Любую ошибку в коде можно исправить, если знать, почему она возникла.

Программная ошибка: что это и почему возникает

Программная ошибка — это дефект в коде. Из-за него программа сбоит или выдает неверные результаты. Некоторые ошибки серьезные — например, блокируют логин и пароль, из-за чего пользователь не может попасть в личный кабинет. А другие незаметны. Некоторое время программа работает как будто бы исправно — и только потом начинает глючить.

Ошибка в программировании — это зачастую ошибки разработчиков, которые находят тестировщики. Запускают разные тесты и отладку, чтобы определить источники проблемы.

Научитесь находить ошибки в приложениях и на сайтах до того, как ими начнут пользоваться клиенты. Для этого освойте профессию «Инженер по тестированию». Изучать язык программирования необязательно. Тестировщик работает с готовыми сайтами, приложениями, сервисами, а не с кодом. В программе от Skypro: четыре проекта для портфолио, практика с обратной связью, все основные инструменты тестировщика.

Ошибки часто называют багами, но подразумевают под ними разное, например:

❗ Ворнинги, или предупреждения. Возникают, когда программа начинает вести себя не так, как задумывалось. Не являются критичными ошибками. Программа с ворнингами работает, но с аномалиями.

❗ Исключения. Это не ошибки, а особые ситуации, которые нужно обработать.

❗ Синтаксические ошибки. Это ошибка в программе, связанная с написанием кода. Пример: программист забыл поставить точку или неверно написал название оператора. Если не исправить, код программы не запустится, а останется просто текстом.

Классификация багов

У багов есть два атрибута — серьезности (Severity) и приоритета (Priority). Серьезность касается технической стороны, а приоритет — организационной.

🚨 По серьезности. Атрибут показывает, как сильно ошибка влияет на общую функциональность программы. Чем выше значение атрибута, тем хуже.

По серьезности баги классифицируют так:

- Blocker — блокирующий баг. Программа запускается, но спустя время баг останавливает ее выполнение. Чтобы снова пользоваться программой, блокирующую ошибку в коде устраняют.

- Critical — критический баг. Нарушает функциональность программы. Появляется в разных частях кода, из-за этого основные функции не выполняются.

- Major — существенный баг. Не нарушает, но затрудняет работу основного функционала программы либо не дает функциям выполняться так, как задумано.

- Minor — незначительный баг. Слабо влияет на функционал программы, но может нарушать работу некоторых дополнительных функций.

- Trivial — тривиальный баг. На работу программы не влияет, но ухудшает общее впечатление. Например, на экране появляются посторонние символы или всё рябит.

🚦 По приоритету. Атрибут показывает, как быстро баг необходимо исправить, пока он не нанес программе приличный ущерб. Бывает таким:

- Top — наивысший. Такой баг — суперсерьезный, потому что может обвалить всю программу. Его устраняют в первую очередь.

- High — высокий. Может затруднить работу программы или ее функций, устраняют как можно скорее.

- Normal — обычный. Баг программу не ломает, просто где-то что-то будет работать не совсем верно. Устраняют в штатном порядке.

- Low — низкий. Баг не влияет на программу. Исправляют, только если у команды есть на это время.

Типы ошибок в программе

🧨 Логические. Приводят к тому, что программа зависает, работает не так, как надо, или выдает неожиданные результаты — например, не записывает файл, а стирает.

Логические ошибки коварны: их трудно обнаружить. Программа выглядит так, будто в ней всё правильно, но при этом работает некорректно. Чтобы победить логические ошибки, специалист должен хорошо ориентироваться в коде программы.

🧨 Синтаксические. Это опечатки в названиях операторов, пропущенные запятые или кавычки. Безобидные ошибки: их обнаруживают и подсвечивают в коде компиляторы, а программисту остается исправить.

🧨 Взаимодействия. Это ошибка в участке кода, который отвечает за взаимодействие с аппаратным или программным окружением. Такая ошибка возникает, например, если неправильно использовать веб-протоколы. Исправляется элементарно: разработчик переписывает нужный кусок кода.

🧨 Компиляционные. Любая программа — это текст. Чтобы он заработал как программа, используют компилятор. Он преобразует программный код в машинный, но одновременно может вызывать ошибки.

Компиляционные баги появляются, если что-то не так с компилятором или в коде есть синтаксические ошибки. Компилятор будто ругается: «Не понимаю, что тут написано. Не знаю, как обработать».

🧨 Ошибки среды выполнения. Возникают, когда программа скомпилирована и уже выглядит как файл — жми и работай. Юзер запускает файл, а программа тормозит и виснет. Причина — нехватка ресурсов, например памяти или буфера.

Такой баг — ошибка разработчика. Он не предвидел реальные условия развертывания программы. Теперь ему надо вернуться в исходный код и поправить фрагмент.

🧨 Арифметические. Бывает, в коде есть числовые переменные и математические формулы. Если где-то проблема — не указаны константы или округление сработало не так, возникает баг. Надо лезть в код и проверять математику.

Инженер-тестировщик: новая работа через 9 месяцев

Получится, даже если у вас нет опыта в IT

Узнать больше

Что такое исключения в программах

Это механизм, который помогает программе обрабатывать нестандартную ситуацию и при этом не вылетать. Идеально, если программист предусмотрел все возможные ситуации. Но так бывает редко, поэтому лучше использовать специальный обработчик. Он обработает исключения так, что программа продолжит работать.

Как это происходит:

- Когда программист кодит, то продумывает, в какой части программы может вылезти ошибка.

- В этой части пишет специальный фрагмент, который предупредит компьютер, что ошибка — вполне ожидаемое явление и резко обрывать программу не нужно.

- Когда юзер запустит программу и появится ошибка, компьютер увидит заранее подготовленное предупреждение программиста. Продолжит выполнять алгоритм так, словно никакого бага и не было.

Исключения бывают программными и аппаратными:

- Аппаратные создает процессор. К ним относят деление на ноль, выход за границы массива, обращение к невыделенной памяти.

- Программные создает операционка и приложения. Возникают, когда программа их инициирует: аномальная ситуация возникла — программа создала исключение.

Как контролировать баги в программе

🔧 Следите за компилятором. Когда компилятор преобразует текст программы в машинный код, то подсвечивает в нём сомнительные участки, которые способны вызывать баги. Некоторые предупреждения не обозначают баг как таковой, а только говорят: «Тут что-то подозрительное». Всё подозрительное надо изучать и прорабатывать, чтобы не было проблемы в будущем.

🔧 Используйте отладчик. Это программа, которая без участия айтишника проверяет, исправно ли работает алгоритм. В случае чего сообщает об ошибках. Например, отладчик используют для построчного выполнения программы. Вместе с тем проверяют значения переменных: фактические сравнивают с ожидаемыми. Если что-то не сходится, ищут баги и исправляют.

🔧 Проводите юнит-тесты. Это когда разработчик или тестировщик описывает ситуации для каждого компонента и указывает, к какому результату должна привести программа. Потом запускает проверку. Если результат не совпадает с ожидаемым, появляется предупреждение. Дальше программисты находят и устраняют проблему.

Ключевое: что такое ошибки в программировании

- Ошибка в программировании — это дефект кода, баг, который может вызывать в программе сбои и неожиданное поведение.

- По серьезности баги делятся на блокирующие, критические, существенные, незначительные, тривиальные. По приоритету — на наивысший, высокий, обычный, низкий.

- Ошибки в коде могут быть разными, например связанные с логикой программы. Или с математическими вычислениями — логические. Еще бывают синтаксические, ошибки взаимодействия, компиляционные и ошибки среды выполнения.

- Некоторые ошибки помогают ловить обработчики исключений.

- Чтобы находить ошибки в коде, тестировщики используют компиляторы, отладчики и пишут юнит-тесты.

A software bug is an error, flaw or fault in the design, development, or operation of computer software that causes it to produce an incorrect or unexpected result, or to behave in unintended ways. The process of finding and correcting bugs is termed «debugging» and often uses formal techniques or tools to pinpoint bugs. Since the 1950s, some computer systems have been designed to deter, detect or auto-correct various computer bugs during operations.

Bugs in software can arise from mistakes and errors made in interpreting and extracting users’ requirements, planning a program’s design, writing its source code, and from interaction with humans, hardware and programs, such as operating systems or libraries. A program with many, or serious, bugs is often described as buggy. Bugs can trigger errors that may have ripple effects. The effects of bugs may be subtle, such as unintended text formatting, through to more obvious effects such as causing a program to crash, freezing the computer, or causing damage to hardware. Other bugs qualify as security bugs and might, for example, enable a malicious user to bypass access controls in order to obtain unauthorized privileges.[1]

Some software bugs have been linked to disasters. Bugs in code that controlled the Therac-25 radiation therapy machine were directly responsible for patient deaths in the 1980s. In 1996, the European Space Agency’s US$1 billion prototype Ariane 5 rocket was destroyed less than a minute after launch due to a bug in the on-board guidance computer program.[2] In 1994, an RAF Chinook helicopter crashed, killing 29; this was initially blamed on pilot error, but was later thought to have been caused by a software bug in the engine-control computer.[3] Buggy software caused the early 21st century British Post Office scandal, the most widespread miscarriage of justice in British legal history.[4]

In 2002, a study commissioned by the US Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology concluded that «software bugs, or errors, are so prevalent and so detrimental that they cost the US economy an estimated $59 billion annually, or about 0.6 percent of the gross domestic product».[5]

History[edit]

The Middle English word bugge is the basis for the terms «bugbear» and «bugaboo» as terms used for a monster.[6]

The term «bug» to describe defects has been a part of engineering jargon since the 1870s[7] and predates electronics and computers; it may have originally been used in hardware engineering to describe mechanical malfunctions. For instance, Thomas Edison wrote in a letter to an associate in 1878:[8]

… difficulties arise—this thing gives out and [it is] then that «Bugs»—as such little faults and difficulties are called—show themselves[9]

Baffle Ball, the first mechanical pinball game, was advertised as being «free of bugs» in 1931.[10] Problems with military gear during World War II were referred to as bugs (or glitches).[11] In a book published in 1942, Louise Dickinson Rich, speaking of a powered ice cutting machine, said, «Ice sawing was suspended until the creator could be brought in to take the bugs out of his darling.»[12]

Isaac Asimov used the term «bug» to relate to issues with a robot in his short story «Catch That Rabbit», published in 1944.

A page from the Harvard Mark II electromechanical computer’s log, featuring a dead moth that was removed from the device

The term «bug» was used in an account by computer pioneer Grace Hopper, who publicized the cause of a malfunction in an early electromechanical computer.[13] A typical version of the story is:

In 1946, when Hopper was released from active duty, she joined the Harvard Faculty at the Computation Laboratory where she continued her work on the Mark II and Mark III. Operators traced an error in the Mark II to a moth trapped in a relay, coining the term bug. This bug was carefully removed and taped to the log book. Stemming from the first bug, today we call errors or glitches in a program a bug.[14]

Hopper was not present when the bug was found, but it became one of her favorite stories.[15] The date in the log book was September 9, 1947.[16][17][18] The operators who found it, including William «Bill» Burke, later of the Naval Weapons Laboratory, Dahlgren, Virginia,[19] were familiar with the engineering term and amusedly kept the insect with the notation «First actual case of bug being found.» This log book, complete with attached moth, is part of the collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.[17]

The related term «debug» also appears to predate its usage in computing: the Oxford English Dictionary‘s etymology of the word contains an attestation from 1945, in the context of aircraft engines.[20]

The concept that software might contain errors dates back to Ada Lovelace’s 1843 notes on the analytical engine, in which she speaks of the possibility of program «cards» for Charles Babbage’s analytical engine being erroneous:

… an analysing process must equally have been performed in order to furnish the Analytical Engine with the necessary operative data; and that herein may also lie a possible source of error. Granted that the actual mechanism is unerring in its processes, the cards may give it wrong orders.

«Bugs in the System» report[edit]

The Open Technology Institute, run by the group, New America,[21] released a report «Bugs in the System» in August 2016 stating that U.S. policymakers should make reforms to help researchers identify and address software bugs. The report «highlights the need for reform in the field of software vulnerability discovery and disclosure.»[22] One of the report’s authors said that Congress has not done enough to address cyber software vulnerability, even though Congress has passed a number of bills to combat the larger issue of cyber security.[22]

Government researchers, companies, and cyber security experts are the people who typically discover software flaws. The report calls for reforming computer crime and copyright laws.[22]

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act and the Electronic Communications Privacy Act criminalize and create civil penalties for actions that security researchers routinely engage in while conducting legitimate security research, the report said.[22]

Terminology[edit]

While the use of the term «bug» to describe software errors is common, many have suggested that it should be abandoned. One argument is that the word «bug» is divorced from a sense that a human being caused the problem, and instead implies that the defect arose on its own, leading to a push to abandon the term «bug» in favor of terms such as «defect», with limited success.[23] Since the 1970s Gary Kildall somewhat humorously suggested to use the term «blunder».[24][25]

In software engineering, mistake metamorphism (from Greek meta = «change», morph = «form») refers to the evolution of a defect in the final stage of software deployment. Transformation of a «mistake» committed by an analyst in the early stages of the software development lifecycle, which leads to a «defect» in the final stage of the cycle has been called ‘mistake metamorphism’.[26]

Different stages of a «mistake» in the entire cycle may be described as «mistakes», «anomalies», «faults», «failures», «errors», «exceptions», «crashes», «glitches», «bugs», «defects», «incidents», or «side effects».[26]

Prevention[edit]

The software industry has put much effort into reducing bug counts.[27][28] These include:

Typographical errors[edit]

Bugs usually appear when the programmer makes a logic error. Various innovations in programming style and defensive programming are designed to make these bugs less likely, or easier to spot. Some typos, especially of symbols or logical/mathematical operators, allow the program to operate incorrectly, while others such as a missing symbol or misspelled name may prevent the program from operating. Compiled languages can reveal some typos when the source code is compiled.

Development methodologies[edit]

Several schemes assist managing programmer activity so that fewer bugs are produced. Software engineering (which addresses software design issues as well) applies many techniques to prevent defects. For example, formal program specifications state the exact behavior of programs so that design bugs may be eliminated. Unfortunately, formal specifications are impractical for anything but the shortest programs, because of problems of combinatorial explosion and indeterminacy.

Unit testing involves writing a test for every function (unit) that a program is to perform.

In test-driven development unit tests are written before the code and the code is not considered complete until all tests complete successfully.

Agile software development involves frequent software releases with relatively small changes. Defects are revealed by user feedback.

Open source development allows anyone to examine source code. A school of thought popularized by Eric S. Raymond as Linus’s law says that popular open-source software has more chance of having few or no bugs than other software, because «given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow».[29] This assertion has been disputed, however: computer security specialist Elias Levy wrote that «it is easy to hide vulnerabilities in complex, little understood and undocumented source code,» because, «even if people are reviewing the code, that doesn’t mean they’re qualified to do so.»[30] An example of an open-source software bug was the 2008 OpenSSL vulnerability in Debian.

Programming language support[edit]

Programming languages include features to help prevent bugs, such as static type systems, restricted namespaces and modular programming. For example, when a programmer writes (pseudocode) LET REAL_VALUE PI = "THREE AND A BIT", although this may be syntactically correct, the code fails a type check. Compiled languages catch this without having to run the program. Interpreted languages catch such errors at runtime. Some languages deliberately exclude features that easily lead to bugs, at the expense of slower performance: the general principle being that, it is almost always better to write simpler, slower code than inscrutable code that runs slightly faster, especially considering that maintenance cost is substantial. For example, the Java programming language does not support pointer arithmetic; implementations of some languages such as Pascal and scripting languages often have runtime bounds checking of arrays, at least in a debugging build.

Code analysis[edit]

Tools for code analysis help developers by inspecting the program text beyond the compiler’s capabilities to spot potential problems. Although in general the problem of finding all programming errors given a specification is not solvable (see halting problem), these tools exploit the fact that human programmers tend to make certain kinds of simple mistakes often when writing software.

Instrumentation[edit]

Tools to monitor the performance of the software as it is running, either specifically to find problems such as bottlenecks or to give assurance as to correct working, may be embedded in the code explicitly (perhaps as simple as a statement saying PRINT "I AM HERE"), or provided as tools. It is often a surprise to find where most of the time is taken by a piece of code, and this removal of assumptions might cause the code to be rewritten.

Testing[edit]

Software testers are people whose primary task is to find bugs, or write code to support testing. On some efforts, more resources may be spent on testing than in developing the program.

Measurements during testing can provide an estimate of the number of likely bugs remaining; this becomes more reliable the longer a product is tested and developed.[citation needed]

Debugging[edit]

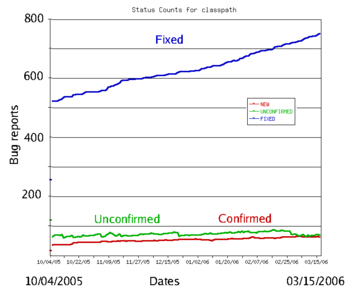

The typical bug history (GNU Classpath project data). A new bug submitted by the user is unconfirmed. Once it has been reproduced by a developer, it is a confirmed bug. The confirmed bugs are later fixed. Bugs belonging to other categories (unreproducible, will not be fixed, etc.) are usually in the minority.

Finding and fixing bugs, or debugging, is a major part of computer programming. Maurice Wilkes, an early computing pioneer, described his realization in the late 1940s that much of the rest of his life would be spent finding mistakes in his own programs.[31]

Usually, the most difficult part of debugging is finding the bug. Once it is found, correcting it is usually relatively easy. Programs known as debuggers help programmers locate bugs by executing code line by line, watching variable values, and other features to observe program behavior. Without a debugger, code may be added so that messages or values may be written to a console or to a window or log file to trace program execution or show values.

However, even with the aid of a debugger, locating bugs is something of an art. It is not uncommon for a bug in one section of a program to cause failures in a completely different section,[citation needed] thus making it especially difficult to track (for example, an error in a graphics rendering routine causing a file I/O routine to fail), in an apparently unrelated part of the system.

Sometimes, a bug is not an isolated flaw, but represents an error of thinking or planning on the part of the programmer. Such logic errors require a section of the program to be overhauled or rewritten. As a part of code review, stepping through the code and imagining or transcribing the execution process may often find errors without ever reproducing the bug as such.

More typically, the first step in locating a bug is to reproduce it reliably. Once the bug is reproducible, the programmer may use a debugger or other tool while reproducing the error to find the point at which the program went astray.

Some bugs are revealed by inputs that may be difficult for the programmer to re-create. One cause of the Therac-25 radiation machine deaths was a bug (specifically, a race condition) that occurred only when the machine operator very rapidly entered a treatment plan; it took days of practice to become able to do this, so the bug did not manifest in testing or when the manufacturer attempted to duplicate it. Other bugs may stop occurring whenever the setup is augmented to help find the bug, such as running the program with a debugger; these are called heisenbugs (humorously named after the Heisenberg uncertainty principle).

Since the 1990s, particularly following the Ariane 5 Flight 501 disaster, interest in automated aids to debugging rose, such as static code analysis by abstract interpretation.[32]

Some classes of bugs have nothing to do with the code. Faulty documentation or hardware may lead to problems in system use, even though the code matches the documentation. In some cases, changes to the code eliminate the problem even though the code then no longer matches the documentation. Embedded systems frequently work around hardware bugs, since to make a new version of a ROM is much cheaper than remanufacturing the hardware, especially if they are commodity items.

Benchmark of bugs[edit]

To facilitate reproducible research on testing and debugging, researchers use curated benchmarks of bugs:

- the Siemens benchmark

- ManyBugs[33] is a benchmark of 185 C bugs in nine open-source programs.

- Defects4J[34] is a benchmark of 341 Java bugs from 5 open-source projects. It contains the corresponding patches, which cover a variety of patch type.

Bug management[edit]

Bug management includes the process of documenting, categorizing, assigning, reproducing, correcting and releasing the corrected code. Proposed changes to software – bugs as well as enhancement requests and even entire releases – are commonly tracked and managed using bug tracking systems or issue tracking systems.[35] The items added may be called defects, tickets, issues, or, following the agile development paradigm, stories and epics. Categories may be objective, subjective or a combination, such as version number, area of the software, severity and priority, as well as what type of issue it is, such as a feature request or a bug.

A bug triage reviews bugs and decides whether and when to fix them. The decision is based on the bug’s priority, and factors such as development schedules. The triage is not meant to investigate the cause of bugs, but rather the cost of fixing them. The triage happens regularly, and goes through bugs opened or reopened since the previous meeting. The attendees of the triage process typically are the project manager, development manager, test manager, build manager, and technical experts.[36][37]

Severity[edit]

Severity is the intensity of the impact the bug has on system operation.[38] This impact may be data loss, financial, loss of goodwill and wasted effort. Severity levels are not standardized. Impacts differ across industry. A crash in a video game has a totally different impact than a crash in a web browser, or real time monitoring system. For example, bug severity levels might be «crash or hang», «no workaround» (meaning there is no way the customer can accomplish a given task), «has workaround» (meaning the user can still accomplish the task), «visual defect» (for example, a missing image or displaced button or form element), or «documentation error». Some software publishers use more qualified severities such as «critical», «high», «low», «blocker» or «trivial».[39] The severity of a bug may be a separate category to its priority for fixing, and the two may be quantified and managed separately.

Priority[edit]

Priority controls where a bug falls on the list of planned changes. The priority is decided by each software producer. Priorities may be numerical, such as 1 through 5, or named, such as «critical», «high», «low», or «deferred». These rating scales may be similar or even identical to severity ratings, but are evaluated as a combination of the bug’s severity with its estimated effort to fix; a bug with low severity but easy to fix may get a higher priority than a bug with moderate severity that requires excessive effort to fix. Priority ratings may be aligned with product releases, such as «critical» priority indicating all the bugs that must be fixed before the next software release.

A bug severe enough to delay or halt the release of the product is called a «show stopper»[40] or «showstopper bug».[41] It is named so because it «stops the show» – causes unacceptable product failure.[41]

Software releases[edit]

It is common practice to release software with known, low-priority bugs. Bugs of sufficiently high priority may warrant a special release of part of the code containing only modules with those fixes. These are known as patches. Most releases include a mixture of behavior changes and multiple bug fixes. Releases that emphasize bug fixes are known as maintenance releases, to differentiate it from major releases that emphasize feature additions or changes.

Reasons that a software publisher opts not to patch or even fix a particular bug include:

- A deadline must be met and resources are insufficient to fix all bugs by the deadline.[42]

- The bug is already fixed in an upcoming release, and it is not of high priority.

- The changes required to fix the bug are too costly or affect too many other components, requiring a major testing activity.

- It may be suspected, or known, that some users are relying on the existing buggy behavior; a proposed fix may introduce a breaking change.

- The problem is in an area that will be obsolete with an upcoming release; fixing it is unnecessary.

- «It’s not a bug, it’s a feature».[43] A misunderstanding has arisen between expected and perceived behavior or undocumented feature.

Types[edit]

In software development, a mistake or error may be introduced at any stage. Bugs arise from oversight or misunderstanding by a software team during specification, design, coding, configuration, data entry or documentation. For example, a relatively simple program to alphabetize a list of words, the design might fail to consider what should happen when a word contains a hyphen. Or when converting an abstract design into code, the coder might inadvertently create an off-by-one error which can be a «<» where «<=» was intended, and fail to sort the last word in a list.

Another category of bug is called a race condition that may occur when programs have multiple components executing at the same time. If the components interact in a different order than the developer intended, they could interfere with each other and stop the program from completing its tasks. These bugs may be difficult to detect or anticipate, since they may not occur during every execution of a program.

Conceptual errors are a developer’s misunderstanding of what the software must do. The resulting software may perform according to the developer’s understanding, but not what is really needed. Other types:

Arithmetic[edit]

In operations on numerical values, problems can arise that result in unexpected output, slowing of a process, or crashing.[44] These can be from a lack of awareness of the qualities of the data storage such as a loss of precision due to rounding, numerically unstable algorithms, arithmetic overflow and underflow, or from lack of awareness of how calculations are handled by different software coding languages such as division by zero which in some languages may throw an exception, and in others may return a special value such as NaN or infinity.

Control flow[edit]

Control flow bugs are those found in processes with valid logic, but that lead to unintended results, such as infinite loops and infinite recursion, incorrect comparisons for conditional statements such as using the incorrect comparison operator, and off-by-one errors (counting one too many or one too few iterations when looping).

Interfacing[edit]

- Incorrect API usage.

- Incorrect protocol implementation.

- Incorrect hardware handling.

- Incorrect assumptions of a particular platform.

- Incompatible systems. A new API or communications protocol may seem to work when two systems use different versions, but errors may occur when a function or feature implemented in one version is changed or missing in another. In production systems which must run continually, shutting down the entire system for a major update may not be possible, such as in the telecommunication industry[45] or the internet.[46][47][48] In this case, smaller segments of a large system are upgraded individually, to minimize disruption to a large network. However, some sections could be overlooked and not upgraded, and cause compatibility errors which may be difficult to find and repair.

- Incorrect code annotations.

Concurrency[edit]

- Deadlock, where task A cannot continue until task B finishes, but at the same time, task B cannot continue until task A finishes.

- Race condition, where the computer does not perform tasks in the order the programmer intended.

- Concurrency errors in critical sections, mutual exclusions and other features of concurrent processing. Time-of-check-to-time-of-use (TOCTOU) is a form of unprotected critical section.

Resourcing[edit]

- Null pointer dereference.

- Using an uninitialized variable.

- Using an otherwise valid instruction on the wrong data type (see packed decimal/binary-coded decimal).

- Access violations.

- Resource leaks, where a finite system resource (such as memory or file handles) become exhausted by repeated allocation without release.

- Buffer overflow, in which a program tries to store data past the end of allocated storage. This may or may not lead to an access violation or storage violation. These are frequently security bugs.

- Excessive recursion which—though logically valid—causes stack overflow.

- Use-after-free error, where a pointer is used after the system has freed the memory it references.

- Double free error.

Syntax[edit]

- Use of the wrong token, such as performing assignment instead of equality test. For example, in some languages x=5 will set the value of x to 5 while x==5 will check whether x is currently 5 or some other number. Interpreted languages allow such code to fail. Compiled languages can catch such errors before testing begins.

Teamwork[edit]

- Unpropagated updates; e.g. programmer changes «myAdd» but forgets to change «mySubtract», which uses the same algorithm. These errors are mitigated by the Don’t Repeat Yourself philosophy.

- Comments out of date or incorrect: many programmers assume the comments accurately describe the code.

- Differences between documentation and product.

Implications[edit]

The amount and type of damage a software bug may cause naturally affects decision-making, processes and policy regarding software quality. In applications such as human spaceflight, aviation, nuclear power, health care, public transport or automotive safety, since software flaws have the potential to cause human injury or even death, such software will have far more scrutiny and quality control than, for example, an online shopping website. In applications such as banking, where software flaws have the potential to cause serious financial damage to a bank or its customers, quality control is also more important than, say, a photo editing application.

Other than the damage caused by bugs, some of their cost is due to the effort invested in fixing them. In 1978, Lientz et al. showed that the median of projects invest 17 percent of the development effort in bug fixing.[49] In 2020, research on GitHub repositories showed the median is 20%.[50]

Residual bugs in delivered product[edit]

In 1994, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center managed to reduce their average number of errors from 4.5 per 1000 lines of code (SLOC) down to 1 per 1000 SLOC.[51]

Another study in 1990 reported that exceptionally good software development processes can achieve deployment failure rates as low as 0.1 per 1000 SLOC.[52] This figure is iterated in literature such as Code Complete by Steve McConnell,[53] and the NASA study on Flight Software Complexity.[54] Some projects even attained zero defects: the firmware in the IBM Wheelwriter typewriter which consists of 63,000 SLOC, and the Space Shuttle software with 500,000 SLOC.[52]

Well-known bugs[edit]

A number of software bugs have become well-known, usually due to their severity: examples include various space and military aircraft crashes. Possibly the most famous bug is the Year 2000 problem or Y2K bug, which caused many programs written long before the transition from 19xx to 20xx dates to malfunction, for example treating a date such as «25 Dec 04» as being in 1904, displaying «19100» instead of «2000», and so on. A huge effort at the end of the 20th century resolved the most severe problems, and there were no major consequences.

The 2012 stock trading disruption involved one such incompatibility between the old API and a new API.

In popular culture[edit]

- In both the 1968 novel 2001: A Space Odyssey and the corresponding 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey, a spaceship’s onboard computer, HAL 9000, attempts to kill all its crew members. In the follow-up 1982 novel, 2010: Odyssey Two, and the accompanying 1984 film, 2010, it is revealed that this action was caused by the computer having been programmed with two conflicting objectives: to fully disclose all its information, and to keep the true purpose of the flight secret from the crew; this conflict caused HAL to become paranoid and eventually homicidal.

- In the English version of the Nena 1983 song 99 Luftballons (99 Red Balloons) as a result of «bugs in the software», a release of a group of 99 red balloons are mistaken for an enemy nuclear missile launch, requiring an equivalent launch response, resulting in catastrophe.

- In the 1999 American comedy Office Space, three employees attempt (unsuccessfully) to exploit their company’s preoccupation with the Y2K computer bug using a computer virus that sends rounded-off fractions of a penny to their bank account—a long-known technique described as salami slicing.

- The 2004 novel The Bug, by Ellen Ullman, is about a programmer’s attempt to find an elusive bug in a database application.[55]

- The 2008 Canadian film Control Alt Delete is about a computer programmer at the end of 1999 struggling to fix bugs at his company related to the year 2000 problem.

See also[edit]

- Anti-pattern

- Bug bounty program

- Glitch removal

- Hardware bug

- ISO/IEC 9126, which classifies a bug as either a defect or a nonconformity

- Orthogonal Defect Classification

- Racetrack problem

- RISKS Digest

- Software defect indicator

- Software regression

- Software rot

- Automatic bug fixing

References[edit]

- ^ Mittal, Varun; Aditya, Shivam (January 1, 2015). «Recent Developments in the Field of Bug Fixing». Procedia Computer Science. International Conference on Computer, Communication and Convergence (ICCC 2015). 48: 288–297. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2015.04.184. ISSN 1877-0509.

- ^ «Ariane 501 — Presentation of Inquiry Board report». www.esa.int. Retrieved January 29, 2022.

- ^ Prof. Simon Rogerson. «The Chinook Helicopter Disaster». Ccsr.cse.dmu.ac.uk. Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ «Post Office scandal ruined lives, inquiry hears». BBC News. February 14, 2022.

- ^ «Software bugs cost US economy dear». June 10, 2009. Archived from the original on June 10, 2009. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Computerworld staff (September 3, 2011). «Moth in the machine: Debugging the origins of ‘bug’«. Computerworld. Archived from the original on August 25, 2015.

- ^ «bug». Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) 5a

- ^ «Did You Know? Edison Coined the Term «Bug»«. August 1, 2013. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- ^ Edison to Puskas, 13 November 1878, Edison papers, Edison National Laboratory, U.S. National Park Service, West Orange, N.J., cited in Hughes, Thomas Parke (1989). American Genesis: A Century of Invention and Technological Enthusiasm, 1870-1970. Penguin Books. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-14-009741-2.

- ^ «Baffle Ball». Internet Pinball Database.

(See image of advertisement in reference entry)

- ^ «Modern Aircraft Carriers are Result of 20 Years of Smart Experimentation». Life. June 29, 1942. p. 25. Archived from the original on June 4, 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2011.

- ^ Dickinson Rich, Louise (1942), We Took to the Woods, JB Lippincott Co, p. 93, LCCN 42024308, OCLC 405243, archived from the original on March 16, 2017.

- ^ FCAT NRT Test, Harcourt, March 18, 2008

- ^ «Danis, Sharron Ann: «Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper»«. ei.cs.vt.edu. February 16, 1997. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ^ James S. Huggins. «First Computer Bug». Jamesshuggins.com. Archived from the original on August 16, 2000. Retrieved September 24, 2012.

- ^ «Bug Archived March 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine», The Jargon File, ver. 4.4.7. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

- ^ a b «Log Book With Computer Bug Archived March 23, 2017, at the Wayback Machine», National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ «The First «Computer Bug», Naval Historical Center. But note the Harvard Mark II computer was not complete until the summer of 1947.

- ^ IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol 22 Issue 1, 2000

- ^ Journal of the Royal Aeronautical Society. 49, 183/2, 1945 «It ranged … through the stage of type test and flight test and ‘debugging’ …»

- ^ Wilson, Andi; Schulman, Ross; Bankston, Kevin; Herr, Trey. «Bugs in the System» (PDF). Open Policy Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Rozens, Tracy (August 12, 2016). «Cyber reforms needed to strengthen software bug discovery and disclosure: New America report – Homeland Preparedness News». Retrieved August 23, 2016.

- ^ «News at SEI 1999 Archive». cmu.edu. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013.

- ^ Shustek, Len (August 2, 2016). «In His Own Words: Gary Kildall». Remarkable People. Computer History Museum. Archived from the original on December 17, 2016.

- ^ Kildall, Gary Arlen (August 2, 2016) [1993]. Kildall, Scott; Kildall, Kristin (eds.). «Computer Connections: People, Places, and Events in the Evolution of the Personal Computer Industry» (Manuscript, part 1). Kildall Family: 14–15. Archived from the original on November 17, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ^ a b «Testing experience : te : the magazine for professional testers». Testing Experience. Germany: testingexperience: 42. March 2012. ISSN 1866-5705. (subscription required)

- ^ Huizinga, Dorota; Kolawa, Adam (2007). Automated Defect Prevention: Best Practices in Software Management. Wiley-IEEE Computer Society Press. p. 426. ISBN 978-0-470-04212-0. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012.

- ^ McDonald, Marc; Musson, Robert; Smith, Ross (2007). The Practical Guide to Defect Prevention. Microsoft Press. p. 480. ISBN 978-0-7356-2253-1.

- ^ «Release Early, Release Often» Archived May 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Eric S. Raymond, The Cathedral and the Bazaar

- ^ «Wide Open Source» Archived September 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Elias Levy, SecurityFocus, April 17, 2000

- ^ Maurice Wilkes Quotes

- ^ «PolySpace Technologies history». christele.faure.pagesperso-orange.fr. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- ^ Le Goues, Claire; Holtschulte, Neal; Smith, Edward K.; Brun, Yuriy; Devanbu, Premkumar; Forrest, Stephanie; Weimer, Westley (2015). «The ManyBugs and IntroClass Benchmarks for Automated Repair of C Programs». IEEE Transactions on Software Engineering. 41 (12): 1236–1256. doi:10.1109/TSE.2015.2454513. ISSN 0098-5589.

- ^ Just, René; Jalali, Darioush; Ernst, Michael D. (2014). «Defects4J: a database of existing faults to enable controlled testing studies for Java programs». Proceedings of the 2014 International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis — ISSTA 2014. pp. 437–440. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.646.3086. doi:10.1145/2610384.2628055. ISBN 9781450326452. S2CID 12796895.

- ^ Allen, Mitch (May–June 2002). «Bug Tracking Basics: A beginner’s guide to reporting and tracking defects». Software Testing & Quality Engineering Magazine. Vol. 4, no. 3. pp. 20–24. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Rex Black (2002). Managing The Testing Process (2Nd Ed.). Wiley India Pvt. Limited. p. 139. ISBN 9788126503131. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ Chris Vander Mey (August 24, 2012). Shipping Greatness — Practical Lessons on Building and Launching Outstanding Software, Learned on the Job at Google and Amazon. O’Reilly Media. pp. 79–81. ISBN 9781449336608.

- ^ Soleimani Neysiani, Behzad; Babamir, Seyed Morteza; Aritsugi, Masayoshi (October 1, 2020). «Efficient feature extraction model for validation performance improvement of duplicate bug report detection in software bug triage systems». Information and Software Technology. 126: 106344. doi:10.1016/j.infsof.2020.106344. S2CID 219733047.

- ^ «5.3. Anatomy of a Bug». bugzilla.org. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013.

- ^ Jones, Wilbur D. Jr., ed. (1989). «Show stopper». Glossary: defense acquisition acronyms and terms (4 ed.). Fort Belvoir, Virginia, USA: Department of Defense, Defense Systems Management College. p. 123. hdl:2027/mdp.39015061290758 – via Hathitrust.

- ^ a b Zachary, G. Pascal (1994). Show-stopper!: the breakneck race to create Windows NT and the next generation at Microsoft. New York: The Free Press. p. 158. ISBN 0029356717 – via archive.org.

- ^ «The Next Generation 1996 Lexicon A to Z: Slipstream Release». Next Generation. No. 15. March 1996. p. 41.

- ^ Carr, Nicholas (2018). «‘It’s Not a Bug, It’s a Feature.’ Trite—or Just Right?». wired.com.

- ^ Di Franco, Anthony; Guo, Hui; Cindy, Rubio-González. «A Comprehensive Study of Real-World Numerical Bug Characteristics» (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- ^ Kimbler, K. (1998). Feature Interactions in Telecommunications and Software Systems V. IOS Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-90-5199-431-5.

- ^ Syed, Mahbubur Rahman (July 1, 2001). Multimedia Networking: Technology, Management and Applications: Technology, Management and Applications. Idea Group Inc (IGI). p. 398. ISBN 978-1-59140-005-9.

- ^ Wu, Chwan-Hwa (John); Irwin, J. David (April 19, 2016). Introduction to Computer Networks and Cybersecurity. CRC Press. p. 500. ISBN 978-1-4665-7214-0.

- ^ RFC 1263: «TCP Extensions Considered Harmful» quote: «the time to distribute the new version of the protocol to all hosts can be quite long (forever in fact). … If there is the slightest incompatibly between old and new versions, chaos can result.»

- ^ Lientz, B. P.; Swanson, E. B.; Tompkins, G. E. (1978). «Characteristics of Application Software Maintenance». Communications of the ACM. 21 (6): 466–471. doi:10.1145/359511.359522. S2CID 14950091.

- ^ Amit, Idan; Feitelson, Dror G. (2020). «The Corrective Commit Probability Code Quality Metric». arXiv:2007.10912 [cs.SE].

- ^ An overview of the Software Engineering Laboratory (PDF) (Report). Maryland, USA: Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA. December 1, 1994. pp41–42 Figure 18; pp43–44 Figure 21. CR-189410; SEL-94-005. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 22, 2022. Retrieved November 22, 2022. (bibliography: An overview of the Software Engineering Laboratory)

- ^ a b Cobb, Richard H.; Mills, Harlan D. (1990). «Engineering software under statistical quality control». IEEE Software. 7 (6): 46. doi:10.1109/52.60601. ISSN 1937-4194. S2CID 538311 – via University of Tennessee – Harlan D. Mills Collection.

- ^ McConnell, Steven C. (1993). Code Complete. Redmond, Washington, USA: Microsoft Press. p. 611. ISBN 9781556154843 – via archive.org.

(Cobb and Mills 1990)

- ^ Holzmann, Gerard (March 6, 2009). «Appendix D – Software Complexity» (PDF). In Dvorak, Daniel L. (ed.). NASA Study on Flight Software Complexity (Report). NASA. pdf frame 109/264. Appendix D p.2. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 8, 2022. Retrieved November 22, 2022. (under NASA Office of the Chief Engineer Technical Excellence Initiative)

- ^ Ullman, Ellen (2004). The Bug. Picador. ISBN 978-1-250-00249-5.

External links[edit]

- «Common Weakness Enumeration» – an expert webpage focus on bugs, at NIST.gov

- BUG type of Jim Gray – another Bug type

- Picture of the «first computer bug» at the Wayback Machine (archived January 12, 2015)

- «The First Computer Bug!» – an email from 1981 about Adm. Hopper’s bug

- «Toward Understanding Compiler Bugs in GCC and LLVM». A 2016 study of bugs in compilers

Ошибки в программировании – дело обычное, хоть и неприятное. В данной статье будет рассказано о том, какими бывают ошибки (баги), а также что собой представляют исключения.

Определение

Ошибка в программировании (или так называемый баг) – это ситуация у разработчиков, при которой определенный код вследствие обработки выдает неверный результат. Причин данному явлению множество: неисправность компилятора, сбои интерфейса, неточности и нарушения в программном коде.

Баги обнаруживаются чаще всего в момент отладки или бета-тестирования. Реже – после итогового релиза готовой программы. Вот несколько вариантов багов:

- Появляется сообщение об ошибке, но приложение продолжает функционировать.

- ПО вылетает или зависает. Никаких предупреждений или предпосылок этому не было. Процедура осуществляется неожиданно для пользователя. Возможен вариант, при котором контент перезапускается самостоятельно и непредсказуемо.

- Одно из событий, описанных ранее, сопровождается отправкой отчетов разработчикам.

Ошибки в программах могут привести соответствующее приложение в негодность, а также к непредсказуемым алгоритмам функционирования. Желательно обнаруживать баги на этапе ранней разработки или тестирования. Лишь в этом случае программист сможет оперативно и относительно недорого внести необходимые изменения в код для отладки ПО.

История происхождения термина

Баг – слово, которое используется разработчиками в качестве сленга. Оно произошло от слова «bug» – «жук». Точно неизвестно, откуда в программировании и IT возник соответствующий термин. Существуют две теории:

- 9 сентября 1945 года ученые из Гарварда тестировали очередную вычислительную машину. Она называлась Mark II Aiken Relay Calculator. Устройство начало работать с ошибками. Когда его разобрали, то ученые заметили мотылька, застрявшего между реле. Тогда некая Грейс Хоппер назвала произошедший сбой упомянутым термином.

- Слово «баг» появилось задолго до появления Mark II. Термин использовался Томасом Эдисоном и указывал на мелкие недочеты и трудности. Во время Второй Мировой войны «bugs» называли проблемы с радарной электроникой.

Второй вариант кажется более реалистичным. Это факт, который подтвержден документально. Со временем научились различать различные типы багов в IT. Далее они будут рассмотрены более подробно.

Как классифицируют

Ошибки работы программ разделяются по разным факторам. Классификация у рядовых пользователей и разработчиков различается. То, что для первых – «просто программа вылетела» или «глючит», для вторых – огромная головная боль. Но существует и общепринятая классификация ошибок. Пример – по критичности:

- Серьезные неполадки. Это нарушения работоспособности приложения, которые могут приводить к непредвиденным крупным изменениям.

- Незначительные ошибки в программах. Чаще всего не оказывают серьезного воздействия на функциональность ПО.

- Showstopper. Критические проблемы в приложении или аппаратном обеспечении. Приводят к выходу программы из строя почти всегда. Для примера можно взять любое клиент-серверное приложение, в котором не получается авторизоваться через логин и пароль.

Последний вариант требует особого внимания со стороны программистов. Их стараются обнаружить и устранить в первую очередь. Критические ошибки могут отложить релиз исходной программы на неопределенный срок.

Также существуют различные виды сбоев в плане частоты проявления: постоянные и «разовые». Вторые встречаются редко, чаще – при определенных настройках и действиях со стороны пользователя. Первые появляются независимо от используемой платформы и выполненных клиентом манипуляций.

Иногда может получиться так, что ошибка возникает только на устройстве конкретного пользователя. В данном случае устранение неполадки требует индивидуального подхода. Иногда – полной замены компьютера. Связано это с тем, что никто не будет редактировать исходный код, когда он «глючит» только у одного пользователя.

Виды

Существуют различные типы ошибок в программах в зависимости от типовых условий использования приложений. Пример – сбои, которые возникают при возрастании нагрузки на оперативную память или центральный процессор устройства. Есть баги граничных условий, сбоя идентификаторов, несовместимости с архитектурой процессора (наиболее распространенная проблема на мобильных устройствах).

Разработчики выделяют следующие типы ошибок по уровню сложности:

- «Борбаг» – «стабильная» неполадка. Она легко обнаруживается на этапе разработки и компилирования. Иногда – во время тестирования наработкой исходной программы.

- «Гейзенбаг» – баги с поддержкой изменения свойств, включая зависимость от среды, в которой было запущено приложение. Сюда относят периодические неполадки в программах. Они могут исчезать на некоторое время, но через какой-то промежуток вновь дают о себе знать.

- «Мандельбаг» – непредвиденные ошибки. Обладают энтропийным поведением. Предсказать, к чему они приведут, практически невозможно.

- «Шрединбаг» – критические неполадки. Приводят к тому, что злоумышленники могут взломать программу. Данный тип ошибок обнаружить достаточно трудно, потому что они никак себя не проявляют.

Также есть классификация «по критичности». Тут всего два варианта – warning («варнинги») и критические весомые сбои. Первые сопровождаются характерными сообщениями и отчетами для разработчиков. Они не представляют серьезной опасности для работоспособности приложения. При компилировании такие сбои легко исправляются. В отдельных случаях компилятор справляется с этой задачей самостоятельно. А вот критические весомые сбои говорят сами за себя. Они приводят к серьезным нарушениям ПО. Исправляются обычно путем проработки логики и значительных изменений программного кода.

Типы багов

Ошибки в программах бывают:

- логическими;

- синтаксическими;

- взаимодействия;

- компиляционные;

- ресурсные;

- арифметические;

- среды выполнения.

Это – основная классификация сбоев в приложениях и операционных системах. Логические, синтаксические и «среды выполнения» встречаются в разработке чаще остальных. На них будет сделан основной акцент.

Ошибки синтаксиса

Синтаксические баги распространены среди новичков. Они относятся к категории «самых безобидных». С данной категорией ошибок способны справиться компиляторы тех или иных языков. Соответствующие инструменты показывают, где допущена неточность. Остается лишь понять, как исправить ее.

Синтаксические ошибки – ошибки синтаксиса, правил языка. Вот пример в Паскале:

Код написан неверно. Согласно действующим синтаксическим нормам, в Pascal в первой строчке нужно в конце поставить точку с запятой.

Логические

Тут стоит выделить обычные и арифметические типы. Вторые возникают, когда программе при работе необходимо вычислить много переменных, но на каком-то этапе расчетов возникают неполадки или нечто непредвиденное. Пример – получение в результатах «бесконечности».

Логические сбои обычного типа – самые сложные и неприятные. Их тяжелее всего обнаружить и исправить. С точки зрения языка программа может быть написана идеально, но работать неправильно. Подобное явление – следствие логической ошибки. Компиляторы их не обнаруживают.

Выше – пример логической ошибки в программе. Тут:

- Происходит сравнение значения i с 15.

- На экран выводится сообщение, если I = 15.

- В заданном цикле i не будет равно 15. Связано это с диапазоном значений – от 1 до 10.

Может показаться, что ошибка безобидная. В приведенном примере так и есть, но в более крупных программах такое явление приводит к серьезным последствиям.

Время выполнения

Run-time сбои – это ошибка времени выполнения программы. Встречается даже когда исходный код лишен логических и синтаксических ошибок. Связаны такие неполадки с ходом выполнения программного продукта. Пример – в процессе функционирования ПО был удален файл, считываемый программой. Если игнорировать подобные неполадки, можно столкнуться с аварийным завершением работы контента.

Самый распространенный пример в данной категории – это неожиданное деление на ноль. Предложенный фрагмент кода с точки зрения синтаксиса и логики написан грамотно. Но, если клиент наберет 0, произойдет сбой системы.

Компиляционный тип

Встречается при разработке на языках высокого уровня. Во время преобразований в машинный тип «что-то идет не так». Причиной служат синтаксические ошибки или сбои непосредственно в компиляторе.

Наличие подобных неполадок делает бета-тестирование невозможным. Компиляционные ошибки устраняются при разработке-отладке.

Ресурсные

Ресурсный тип ошибок – это сбои вроде «переполнение буфера» или «нехватка памяти». Тесно связаны с «железом» устройства. Могут быть вызваны действиями пользователя. Пример – запуск «свежих» игр на стареньких компьютерах.

Исправить ситуацию помогают основательные работы над исходным кодом. А именно – полное переписывание программы или «проблемного» фрагмента.

Взаимодействие

Подразумевается взаимодействие с аппаратным или программным окружением. Пример – ошибка при использовании веб-протоколов. Это приведет к тому, что облачный сервис не будет нормально функционировать. При постоянном возникновении соответствующей неполадки остается один путь – полностью переписывать «проблемный» участок кода, ответственный за соответствующий баг.

Исключения и как избежать багов

Исключение – событие, при возникновении которых начинается «неправильное» поведение программы. Механизм, необходимый для стабилизации обработки неполадок независимо от типа ПО, платформ и иных условий. Помогают разрабатывать единые концепции ответа на баги со стороны операционной системы или контента.

Исключения бывают:

- Программными. Они генерируются приложением или ОС.

- Аппаратными. Создаются процессором. Пример – обращение к невыделенной памяти.

Исключения нужны для охвата критических багов. Избежать неполадок помогут отладчики на этапе разработки. А еще – своевременное поэтапное тестирование программы.

P. S. Большой выбор курсов по тестированию есть и в Otus. Присутствуют варианты как для продвинутых, так и для начинающих пользователей.

Программная

ошибка

– это расхождение между программой и

её спецификацией, причём тогда и только

тогда, когда спецификация существует

и она правильная.

Программная

ошибка

– это ситуация, когда программа не

делает того, чего пользователь от неё

вполне обоснованно ожидает.

Ошибки

пользовательского интерфейса.

С программой может быть трудно (или даже

невозможно) работать по множеству

причин. Их все можно объединить под

названием “ошибки пользовательского

интерфейса”. Вот несколько разновидностей

таких ошибок.

Функциональность.

Функциональные недостатки имеют место,

если программа не делает того, что

должна, выполняет одну из своих функций

плохо или не полностью. Хотя функции

программы достаточно подробно описываются

в ее спецификации, окончательное

представление о том, что программа

должна делать, существует только в умах

ее пользователей.

Функциональные

недостатки есть абсолютно у всех

программ, поскольку ожидания пользователей

— вещь субъективная: у разных пользователей

они различны. Оправдать их все просто

невозможно, а попытка этого добиться

может привести лишь к усложнению и

потере концептуальной целостности

программного продукта.

Однако

во многих случаях функциональный

недостаток вполне очевиден. Если

предусмотренную программой задачу

трудно выполнить, если она решается

неуклюже или при определенных

обстоятельствах вообще не может быть

решена — проблема налицо. И когда ожидания

пользователей вполне разумны и

обоснованны, эту проблему без колебаний

можно назвать ошибкой.

Взаимодействие

программы с пользователем. Насколько

сложно пользователю разобраться в том,

как работать с программой? Откуда вообще

он об этом узнает? Как обстоит дело с

экранными инструкциями и подсказками?

Достаточно ли их? Понятны ли они? Имеется

ли в программе интерактивная справка

и может ли пользователь в случае

затруднений найти в ней реальную помощь?

Насколько корректно программа сообщает

пользователю о его ошибках и объясняет,

как их исправить? Нет ли в программе

элементов, которые могут раздражать

пользователя, сбивать его с толку или

просто выглядеть неуклюже?

Организация

программы.

Насколько легко потеряться в вашей

программе? Нет ли в ней непонятных команд

или таких, которые легко спутать между

собой? Какие ошибки чаще всего делает

пользователь, на что он тратит больше

всего времени и почему?

Пропущенные

команды.

Чего в программе не хватает? Не заставляет

ли программа выполнять некоторые

действия странным, неестественным или

крайне неэффективным способом? Нельзя

ли привести ее в соответствие с привычным

стилем пользователя? Допускает ли она

хотя бы некоторую степень настройки?

Производительность.

В интерактивном программном обеспечении

очень важна скорость. Плохо, если у

пользователя создается впечатление,

что программа работает медленно, если

он чувствует задержки в ее реакции

(особенно если конкурирующие программы

работают ощутимо быстрее).

Выходные

данные.

Большинство программ так или иначе

формируют выходные данные: отображают

информацию на экране, печатают ее или

сохраняют в файлах. Получаете ли вы то,

что хотите? Правильно ли формируются

отчеты, наглядны ли диаграммы и достаточно

ли отчетливо они выглядят на бумаге?

Сохраняются ли данные в формате, доступном

и для других аналогичных программ?

Обладает ли программа достаточной

гибкостью, чтобы можно было подстраивать

ее под нужды конкретного пользователя?

Обработка

ошибок. Процедуры

обработки ошибок — это очень важная

часть программы. Но, к сожалению, в них

тоже очень часто встречаются ошибки.

Кроме того, правильно определив ошибку,

программа не всегда выдает о ней

достаточно информативное сообщение.

Ошибки,

связанные с обработкой граничных

условий.

Простейшими граничными условиями

являются числовые. Но существует и много

других граничных ситуаций. Любой аспект

работы программы к которому применимы

понятия больше или меньше, раньше или

позже, первый или последний, короче или

длиннее, обязательно должен быть проверен

на границах диапазона. Внутри диапазонов

программа обычно работает прекрасно,

а вот на их границах случаются самые

неожиданные отклонения.

Ошибки

вычислений.

Программирование даже самых простых

арифметических операций чревато

ошибками. Нечего и говорить о сложных

формулах и расчетах. Одними из самых

распространенных среди математических

ошибок являются ошибки округления.

После нескольких промежуточных вычислений

может оказаться, что 2 + 2 = -1, даже если

на промежуточных этапах не было логических

ошибок.

Ошибки

начального и последующих состояний.

Бывает, что при выполнении какой-либо

функции программы сбой происходит

только однажды — при самом первом

обращении к этой функции. Причиной

такого поведения программы может быть

отсутствие файла с инициализационной

информацией. После первого же запуска

программа создаст такой файл, и дальше

все будет в порядке. Получается, что

такую ошибку невозможно повторить

(точнее, для ее повторения нужно установить

новую копию программы). Но не стоит

думать, что ошибка, проявляющаяся только

при первом запуске программы, безвредна:

ведь это будет первое, с чем столкнется

каждый новый пользователь. Иногда,

программируя процесс, связанный с

последовательными преобразованиями

информации, разработчики забывают о

том, что пользователю может понадобиться

вернуться к исходным данным и изменить

их. Насколько корректно поведет себя

программа в такой ситуации? Позволит

ли она внести нужные изменения и не

будет ли из-за этого потеряна вся

выполненная пользователем работа? Что

увидит пользователь при возвращении к

исходному состоянию программы: свои

данные или стандартные значения, которыми

программа инициализирует переменные

при запуске?

Ошибки

передачи или интерпретации данных.

Один модуль может передавать данные

другому или даже другой программе.

Некоторые данные могут передаваться

между модулями множество раз, и на

каком-то этапе они могут быть разрушены

или неверно интерпретированы. Изменения,

внесенные одной из частей программы,

могут потеряться или достичь не всех

частей системы, где они важны.

Ситуация

гонок. Классическая

ситуация гонок описывается так.

Предположим, в системе ожидаются два

события, А и Б. Первым может произойти

любое из них. Но если первым произойдет

событие А, выполнение программы

продолжится, а если первым наступит

событие Б, то в работе программы произойдет

сбой. Программист полагал, что первым

всегда должно быть событие А, и не ожидал,

что Б может выиграть гонки. Тестировать

ситуации гонок довольно сложно. Наиболее

типичны они для систем, где параллельно

выполняются взаимодействующие процессы

и потоки, а также для многопользовательских

систем реального времени. Ошибки в таких

системах трудно воспроизвести, и на их

выявление обычно требуется очень много

времени.

Перегрузки.

Программа может не справляться с

повышенными нагрузками. Например, она

может не выдерживать интенсивной и

длительной эксплуатации или не справляться

со слишком большими объемами данных.

Кроме того, сбои могут происходить из-за

нехватки памяти или отсутствия других

необходимых ресурсов. У каждой программы

свои пределы. Вопрос в том, соответствуют

ли реальные возможности и требования

программы к ресурсам спецификации, и

как программа себя поведет при перегрузках.

Некорректная

работа с аппаратным обеспечением.

Программы могут посылать устройствам

неверные данные, игнорировать сообщения

об ошибках, пытаться использовать

устройства, которые заняты или вообще

отсутствуют. Даже если нужное устройство

просто сломано, программа должна понять

это, а не сбоить при попытке к нему

обратится.

Ошибки

документации.

Сама по себе документация не является

программным обеспечением, но все же это

часть программного продукта. И если она

плохо написана, пользователь может

подумать, что и сама программа не намного

лучше.

Ошибки

тестирования.

Обнаружение ошибок, допущенных

тестировщиками, — дело обычное. Конечно,

если таких ошибок будет слишком много,

вы быстро потеряете доверие остальных

членов команды. Но нужно иметь в виду,

что иногда ошибки тестировщика отражают

проблемы пользовательского интерфейса:

если программа заставляет пользователя

делать ошибки, значит, с ней что-то не

так. Конечно, многие ошибки тестирования

вызваны просто неверными тестовыми

данными.

Характерные

ошибки программирования:

-

Вид

ошибкиПример

Неправильная

постановка задачиПравильное

решение неверно сформулированной

задачиНеверный

метод (алгоритм)Выбор

метода (алгоритма) приводящего к

неточному

или не эффективному решению

задачЛогические

ошибкиНеполный

учет ситуаций, которые могут

возникнутьНапример,

-

неверное

указание ветви алгоритма после

проверки некоторого условия, -

неверное

условие выполнения или окончания

цикла, -

неполный

учет возможных условий, -

пропуск

в программе одного или более блоков

алгоритма.

Семантические

ошибкиНепонимание

работы оператораСинтаксические

ошибкиНарушение

правил установленных в

данном языке программированияНапример,

-

неправильная

запись формата оператора, -

повторное

использование имени переменной для

обозначения другой, -

ошибочное

использование одной переменной

вместо другой, -

несогласованность

скобок, -

пропуск

разделителей.

Ошибки

времени выполненияНапример,

в Delphi, они называются исключениями

(exception), как правило, легко устранимы.

Они обычно проявляются уже при первых

запусках программы и во время

тестирования. При возникновении

ошибки в программе, запущенной из

Delphi, среда разработки прерывает работу

программы, и на экране появляется

диалоговое окно, которое содержит

сообщение об ошибке и информацию о

типе (классе) ошибки. -

Вопросы

для самопроверки:

-

Дайте

определение понятия «программная

ошибка». -

Перечислите

источники ошибок

программного обеспечения. -

Классифицируйте

ошибки программного обеспечения.

Соседние файлы в предмете [НЕСОРТИРОВАННОЕ]

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

- #

Программная

ошибка

– это расхождение между программой и

её спецификацией, причём тогда и только

тогда, когда спецификация существует

и она правильная.

Программная

ошибка

– это ситуация, когда программа не

делает того, чего пользователь от неё

вполне обоснованно ожидает.

Ошибки

пользовательского интерфейса.

С программой может быть трудно (или даже

невозможно) работать по множеству

причин. Их все можно объединить под

названием “ошибки пользовательского

интерфейса”. Вот несколько разновидностей

таких ошибок.

Функциональность.

Функциональные недостатки имеют место,

если программа не делает того, что

должна, выполняет одну из своих функций

плохо или не полностью. Хотя функции

программы достаточно подробно описываются

в ее спецификации, окончательное

представление о том, что программа

должна делать, существует только в умах

ее пользователей.

Функциональные

недостатки есть абсолютно у всех

программ, поскольку ожидания пользователей

— вещь субъективная: у разных пользователей

они различны. Оправдать их все просто

невозможно, а попытка этого добиться

может привести лишь к усложнению и

потере концептуальной целостности

программного продукта.

Однако

во многих случаях функциональный

недостаток вполне очевиден. Если

предусмотренную программой задачу

трудно выполнить, если она решается

неуклюже или при определенных

обстоятельствах вообще не может быть

решена — проблема налицо. И когда ожидания

пользователей вполне разумны и

обоснованны, эту проблему без колебаний

можно назвать ошибкой.

Взаимодействие

программы с пользователем. Насколько

сложно пользователю разобраться в том,

как работать с программой? Откуда вообще

он об этом узнает? Как обстоит дело с

экранными инструкциями и подсказками?

Достаточно ли их? Понятны ли они? Имеется

ли в программе интерактивная справка

и может ли пользователь в случае

затруднений найти в ней реальную помощь?

Насколько корректно программа сообщает

пользователю о его ошибках и объясняет,

как их исправить? Нет ли в программе

элементов, которые могут раздражать

пользователя, сбивать его с толку или

просто выглядеть неуклюже?

Организация

программы.

Насколько легко потеряться в вашей

программе? Нет ли в ней непонятных команд

или таких, которые легко спутать между

собой? Какие ошибки чаще всего делает

пользователь, на что он тратит больше

всего времени и почему?

Пропущенные

команды.

Чего в программе не хватает? Не заставляет

ли программа выполнять некоторые

действия странным, неестественным или

крайне неэффективным способом? Нельзя

ли привести ее в соответствие с привычным

стилем пользователя? Допускает ли она

хотя бы некоторую степень настройки?

Производительность.

В интерактивном программном обеспечении

очень важна скорость. Плохо, если у

пользователя создается впечатление,

что программа работает медленно, если

он чувствует задержки в ее реакции

(особенно если конкурирующие программы

работают ощутимо быстрее).

Выходные

данные.

Большинство программ так или иначе

формируют выходные данные: отображают

информацию на экране, печатают ее или

сохраняют в файлах. Получаете ли вы то,

что хотите? Правильно ли формируются

отчеты, наглядны ли диаграммы и достаточно

ли отчетливо они выглядят на бумаге?

Сохраняются ли данные в формате, доступном

и для других аналогичных программ?

Обладает ли программа достаточной

гибкостью, чтобы можно было подстраивать

ее под нужды конкретного пользователя?

Обработка

ошибок. Процедуры

обработки ошибок — это очень важная

часть программы. Но, к сожалению, в них

тоже очень часто встречаются ошибки.

Кроме того, правильно определив ошибку,

программа не всегда выдает о ней

достаточно информативное сообщение.

Ошибки,

связанные с обработкой граничных

условий.

Простейшими граничными условиями

являются числовые. Но существует и много

других граничных ситуаций. Любой аспект

работы программы к которому применимы

понятия больше или меньше, раньше или

позже, первый или последний, короче или

длиннее, обязательно должен быть проверен

на границах диапазона. Внутри диапазонов

программа обычно работает прекрасно,

а вот на их границах случаются самые

неожиданные отклонения.

Ошибки

вычислений.

Программирование даже самых простых

арифметических операций чревато

ошибками. Нечего и говорить о сложных

формулах и расчетах. Одними из самых

распространенных среди математических

ошибок являются ошибки округления.

После нескольких промежуточных вычислений

может оказаться, что 2 + 2 = -1, даже если

на промежуточных этапах не было логических

ошибок.

Ошибки

начального и последующих состояний.

Бывает, что при выполнении какой-либо

функции программы сбой происходит

только однажды — при самом первом

обращении к этой функции. Причиной

такого поведения программы может быть

отсутствие файла с инициализационной

информацией. После первого же запуска

программа создаст такой файл, и дальше

все будет в порядке. Получается, что

такую ошибку невозможно повторить

(точнее, для ее повторения нужно установить

новую копию программы). Но не стоит

думать, что ошибка, проявляющаяся только

при первом запуске программы, безвредна:

ведь это будет первое, с чем столкнется

каждый новый пользователь. Иногда,

программируя процесс, связанный с

последовательными преобразованиями

информации, разработчики забывают о

том, что пользователю может понадобиться

вернуться к исходным данным и изменить

их. Насколько корректно поведет себя

программа в такой ситуации? Позволит

ли она внести нужные изменения и не

будет ли из-за этого потеряна вся

выполненная пользователем работа? Что

увидит пользователь при возвращении к

исходному состоянию программы: свои

данные или стандартные значения, которыми

программа инициализирует переменные

при запуске?

Ошибки

передачи или интерпретации данных.

Один модуль может передавать данные

другому или даже другой программе.

Некоторые данные могут передаваться

между модулями множество раз, и на

каком-то этапе они могут быть разрушены

или неверно интерпретированы. Изменения,

внесенные одной из частей программы,

могут потеряться или достичь не всех

частей системы, где они важны.

Ситуация

гонок. Классическая

ситуация гонок описывается так.

Предположим, в системе ожидаются два

события, А и Б. Первым может произойти

любое из них. Но если первым произойдет

событие А, выполнение программы

продолжится, а если первым наступит

событие Б, то в работе программы произойдет

сбой. Программист полагал, что первым

всегда должно быть событие А, и не ожидал,

что Б может выиграть гонки. Тестировать

ситуации гонок довольно сложно. Наиболее

типичны они для систем, где параллельно

выполняются взаимодействующие процессы

и потоки, а также для многопользовательских

систем реального времени. Ошибки в таких

системах трудно воспроизвести, и на их

выявление обычно требуется очень много

времени.

Перегрузки.

Программа может не справляться с

повышенными нагрузками. Например, она

может не выдерживать интенсивной и

длительной эксплуатации или не справляться

со слишком большими объемами данных.

Кроме того, сбои могут происходить из-за

нехватки памяти или отсутствия других

необходимых ресурсов. У каждой программы

свои пределы. Вопрос в том, соответствуют

ли реальные возможности и требования

программы к ресурсам спецификации, и

как программа себя поведет при перегрузках.

Некорректная

работа с аппаратным обеспечением.

Программы могут посылать устройствам

неверные данные, игнорировать сообщения

об ошибках, пытаться использовать

устройства, которые заняты или вообще

отсутствуют. Даже если нужное устройство

просто сломано, программа должна понять

это, а не сбоить при попытке к нему

обратится.

Ошибки

документации.

Сама по себе документация не является

программным обеспечением, но все же это

часть программного продукта. И если она

плохо написана, пользователь может

подумать, что и сама программа не намного

лучше.

Ошибки

тестирования.

Обнаружение ошибок, допущенных

тестировщиками, — дело обычное. Конечно,

если таких ошибок будет слишком много,

вы быстро потеряете доверие остальных

членов команды. Но нужно иметь в виду,

что иногда ошибки тестировщика отражают

проблемы пользовательского интерфейса:

если программа заставляет пользователя

делать ошибки, значит, с ней что-то не

так. Конечно, многие ошибки тестирования

вызваны просто неверными тестовыми

данными.

Характерные

ошибки программирования: