2 solutions to fix the SQL Server error : violation of unique key constraint cannot insert duplicate key.

How to avoid and fix the Violation of unique key constraint, cannot insert duplicate key error during SQL Server development? Insert or update data in an SQL Server table with a simple query? Here are two simple solutions to execute an update or insert and avoid errors. The SQL Server error message is : Violation of UNIQUE KEY constraint . Cannot insert duplicate key in object . The duplicate key value is… The error appears because the line you are inserting already exists in the target table.

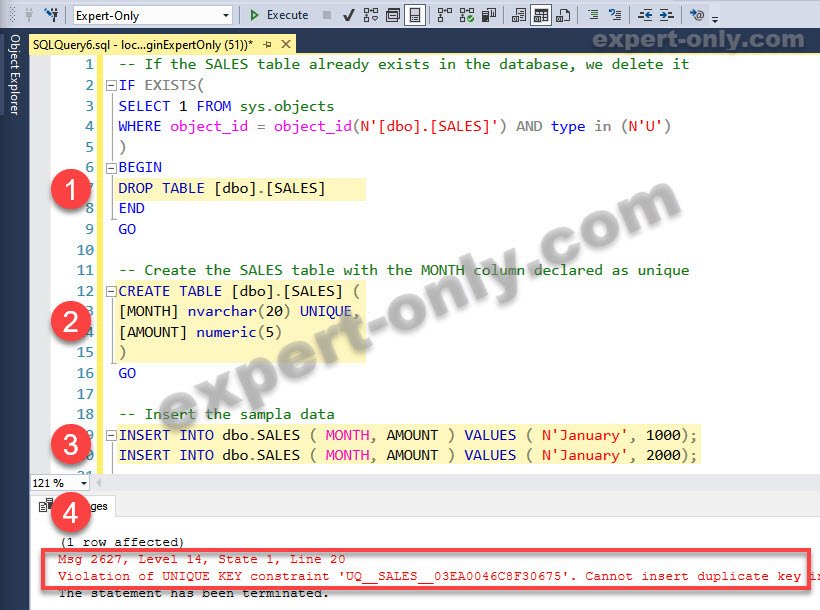

1. Create the sample SQL Server table with a constraint

Indeed, this SQL Server script creates a table with two columns: [Month] and [Amount]. In other words the month and the number of sales realized. Please note that the [Month] column as the UNIQUE keyword, so the table cannot store two lines for the same month. Please execute this query first before using the solution queries. It’s creating a Sales sample table through these steps and results:

- Drop the table if it already in the database

- Create the sales sample table with a unicity constraint on the Month column

- Insert 2 lines with the same month, i.e. January

- Once the script is executed, it trigger the unique constraint error.

-- If the SALES table already exists in the database, we delete it IF EXISTS( SELECT 1 FROM sys.objects WHERE object_id = object_id(N'[dbo].[SALES]') AND type in (N'U') ) BEGIN DROP TABLE [dbo].[SALES] END GO -- Create the SALES table with the MONTH column declared as unique CREATE TABLE [dbo].[SALES] ( [MONTH] nvarchar(20) UNIQUE, [AMOUNT] numeric(5) ) GO -- Insert the sampla data INSERT INTO dbo.SALES ( MONTH, AMOUNT ) VALUES ( N'January', 1000); INSERT INTO dbo.SALES ( MONTH, AMOUNT ) VALUES ( N'January', 2000);

The error message displayed:

(1 row affected)

Msg 2627, Level 14, State 1, Line 20

Violation of UNIQUE KEY constraint ‘UQ__SALES__03EA0046C8F30675’. Cannot insert duplicate key in object ‘dbo.SALES’. The duplicate key value is (January).

The statement has been terminated.

To avoid the SQL Server violation of unique key error, 2 different but very similar solutions exists:

- Do a simple INSERT or UPDATE : check if the line is in the table, and do an INSERT or an UPDATE.

- Do an UPDATE on the table and count the lines updated, if it is 0 then perform the INSERT.

2. Avoid the violation of unique key constraint error using insert or update

Firstly, one solution is to use the EXISTS() function to check if a line with ‘January’ Month value already exists in the table. If no line exists then we insert the sale for 2000$ instead of 1000$.

IF NOT EXISTS(SELECT * FROM dbo.SALES WHERE MONTH = 'January')

BEGIN

INSERT INTO dbo.SALES ( MONTH, AMOUNT )

VALUES ( N'January', 2000)

END

ELSE

BEGIN

UPDATE dbo.SALES

SET AMOUNT = 2000

WHERE MONTH = 'January'

END

3. Fix the insertion of duplicate key error with an update or insert

Secondly, the other solution is to update the table, then check the number of lines updated. If the number equals zero, then no line exists in the table. And we can insert our line with 2000$ as sales amount using a classical INSERT statement.

UPDATE dbo.SALES SET AMOUNT = 2000 WHERE MONTH = 'January' IF @@ROWCOUNT = 0 BEGIN INSERT INTO dbo.SALES ( MONTH, AMOUNT ) VALUES ( N'January', 2000) END

4. Conclusion on T-SQL unique key constraint error

In conclusion, we have explored two distinct solutions to avoid the Violation of unique key constraint cannot insert duplicate key error in SQL Server. Both methods utilize INSERT and UPDATE statements to handle this issue effectively. The first approach checks if the record exists and performs either an INSERT or an UPDATE, while the second method uses an UPDATE followed by an INSERT if no rows were affected by the UPDATE.

By employing these strategies, you can prevent the violation of unique key constraints and ensure data integrity within your database. Additionally, understanding these techniques will help you to address other related errors, such as the Arithmetic overflow error, and improve your overall SQL Server expertise.

The database developer can, of course, throw all errors back to the application developer to deal with, but this is neither kind nor necessary. How errors are dealt with is very dependent on the application, but the process itself isn’t entirely obvious. Phil became gripped with a mission to explain…

In this article, we’re going to take a problem and use it to explore transactions, and constraint violations, before suggesting a solution to the problem.

The problem is this: we have a database which uses constraints; lots of them. It does a very solid job of checking the complex rules and relationships governing the data. We wish to import a batch of potentially incorrect data into the database, checking for constraint violations without throwing errors back at any client application, reporting what data caused the errors, and either rolling back the import or just the offending rows. This would then allow the administrator to manually correct the records and re-apply them.

Just to illustrate various points, we’ll take the smallest possible unit of this problem, and provide simple code that you can use to experiment with. We’ll be exploring transactions and constraint violations

Transactions

Transactions enable you to keep a database consistent, even after an error. They underlie every SQL data manipulation in order to enforce atomicity and consistency. They also enforce isolation, in that they also provide the way of temporarily isolating a connection from others that are accessing the database at the same time whilst a single unit of work is done as one or more SQL Statements. Any temporary inconsistency of the data is visible only to the connection. A transaction is both a unit of work and a unit of recovery. Together with constraints, transactions are the best way of ensuring that the data stored within the database is consistent and error-free.

Each insert, update, and delete statement is considered a single transaction (Autocommit, in SQL Server jargon). However, only you can define what you consider a ‘unit of work’ which is why we have explicit transactions. Using explicit transactions in SQL Server isn’t like sprinkling magic dust, because of the way that error-handling and constraint-checking is done. You need to be aware how this rather complex system works in order to avoid some of the pitfalls when you are planning on how to recover from errors.

Any good SQL Server database will use constraints and other DRI in order to maintain integrity and increase performance. The violation of any constraints leads to an error, and it is rare to see this handled well.

Autocommit transaction mode

Let’s create a table that allows us to be able to make a couple of different constraint violations. You’ll have to imagine that this is a part of a contact database that is full of constraints and triggers that will defend against bad data ever reaching the database. Naturally, there will be more in this table. It might contain the actual address that relates to the PostCode(in reality, it isn’t a one-to-one correspondence).

|

CREATE TABLE PostCode ( Code VARCHAR(10) PRIMARY KEY CHECK ( Code LIKE ‘[A-Z][A-Z0-9] [0-9][ABD-HJLNP-UW-Z][ABD-HJLNP-UW-Z]’ OR Code LIKE ‘[A-Z][A-Z0-9]_ [0-9][ABD-HJLNP-UW-Z][ABD-HJLNP-UW-Z]’ OR Code LIKE ‘[A-Z][A-Z0-9]__ [0-9][ABD-HJLNP-UW-Z][ABD-HJLNP-UW-Z]’ ) ); |

Listing 1: Creating the PostCodetable

This means that PostCodes in this table must be unique and they must conform to a specific pattern. Since SQL Databases are intrinsically transactional, those DML (Data Manipulation Language) statements that trigger an error will be rolled back. Assuming our table is empty, try this…

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 |

Delete from PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’ AS PostCode UNION ALL SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘CR AZY’ —this is an invalid PostCode UNION ALL SELECT ‘G2 9AG’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; —a duplicate SELECT * FROM PostCode—none there Msg 547, Level 16, State 0, Line 3 The INSERT statement conflicted with the CHECK constraint «CK__PostCode__Code__4AB81AF0«. The conflict occurred in database «contacts«, table «dbo.PostCode«, column ‘Code’. The statement has been terminated. Code ———- (0 row(s) affected) |

Listing 2: Inserting rows in a single statement (XACT_ABORT OFF)

Nothing there, is there? It found the bad PostCodebut never got to find the duplicate, did it? So, this single statement was rolled back, because the CHECK constraint found the invalid PostCode. Would this rollback the entire batch? Let’s try doing some insertions as separate statements to check this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

SET XACT_ABORT OFF — confirm that XACT_ABORT is OFF (the default) DELETE FROM PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’ AS PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR AZY’ —this is an invalid PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; —a duplicate. Not allowed SELECT * FROM PostCode Msg 547, Level 16, State 0, Line 5 The INSERT statement conflicted with the CHECK constraint «CK__PostCode__Code__4AB81AF0«. The conflict occurred in database «contacts«, table «dbo.PostCode«, column ‘Code’. The statement has been terminated. Msg 2627, Level 14, State 1, Line 7 Violation of PRIMARY KEY constraint ‘PK__PostCode__A25C5AA648CFD27E’. Cannot insert duplicate key in object ‘dbo.PostCode’. The statement has been terminated. Code ———- CM8 3BY G2 9AG W6 8JB |

Listing 3: Single batch using separate INSERT statements (XACT_ABORT OFF)

Not only doesn’t it roll back the batch when it hits a constraint violation, but just the statement. It then powers on and finds the UNIQUE constraint violation. As it wasn’t judged as a severe ‘batch-aborting’ error, SQL Server only rolled back the two offending inserts. If, however, we substitute SET XACT_ABORT ON then the entire batch is aborted at the first error, leaving the two first insertions in place. The rest of the batch isn’t even executed. Try it.

By setting XACT_ABORT ON, we are telling SQL Server to react to any error by rolling back the entire transaction and aborting the batch. By default, the session setting is OFF. In this case, SQL Server merely rolls back the Transact-SQL statement that raised the error and the batch continues. Even with SET XACT_ABORT set to OFF, SQL Server will choose to roll back a whole batch if it hits more severe errors.

If we want to clean up specific things after an error, or if we want processing to continue in the face of moderate errors, then we need to use SET XACT_ABORT OFF, but there is a down-side: It is our responsibility now to make sure we can return the database to a consistent state on error…and use appropriate error handling to deal with even the trickier errors such as those caused by a cancel/timeout of the session in the middle of a transaction.

Just by changing the setting of XACT_ABORT, we can rerun the example and end up with different data in the database. This is because, with XACT_ABORT ON, the behavior is consistent regardless of the type of error. It simply assumes the transaction just can’t be committed, stops processing, and aborts the batch.

With XACT_ABORT OFF, the behavior depends on the type of error. If it’s a constraint violation, permission-denial, or a divide-by-zero, it will plough on. If the error dooms the transaction, such as when there is a conversion error or deadlock, it won’t. Let’s illustrate this draconian batch-abortion.

|

DELETE FROM PostCode GO SET XACT_ABORT ON—or off. Try it both ways INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’ AS PostCode UNION ALL SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘CR AZY’ —this is an invalid PostCode UNION ALL SELECT ‘G2 9AG’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; —a duplicate INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ GO |

Listing 4: Inserting rows in a batch using separate INSERT statements (XACT_ABORT ON)

If you’ve got the XACT_ABORT ON then you’ll get…

|

Msg 2627, Level 14, State 1, Line 4 Violation of PRIMARY KEY constraint ‘PK__PostCode__A25C5AA648CFD27E’. Cannot insert duplicate key in object ‘dbo.PostCode’. Code ———- CM8 3BY |

You’ll see that, in the second batch, the PostCode ‘G2 9AG’ never gets inserted because the batch is aborted after the first constraint violation.

If you set XACT_ABORT OFF, then you’ll get …

|

Msg 2627, Level 14, State 1, Line 4 Violation of PRIMARY KEY constraint ‘PK__PostCode__A25C5AA648CFD27E’. Cannot insert duplicate key in object ‘dbo.PostCode’. The statement has been terminated. (1 row(s) affected) Code ———- CM8 3BY G2 9AG |

And to our surprise, we can see that we get a different result depending on the setting of XACT_ABORT. (Remember that GO is a client-side batch separator!) You’ll see that, if we insert a GO after the multi-row insert, we get the same two PostCodes in . Yes, With XACT_ABORT ON the behavior is consistent regardless of the type of error. With XACT_ABORT OFF, behavior depends on the type of error

There is a great difference in the ‘abortion’ of a batch, and a ‘rollback’. With an ‘abortion’, any further execution of the batch is always abandoned. This will happen whatever you specified for XACT_ABORT. If a type of error occurs that SQL Server considers too severe to allow you to ever commit the transaction, it is ‘doomed’. This happens whether you like it or not. The offending statement is rolled back and the batch is aborted.

Let’s ‘doom’ the batch by putting in a conversion error.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

SET XACT_ABORT OFF — confirm that XACT_ABORT is OFF (the default) DELETE FROM PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’ AS PostCode; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR AZY’+1; —this is an invalid PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; —a duplicate. Not allowed PRINT ‘that went well!’ GO SELECT * FROM PostCode Msg 245, Level 16, State 1, Line 7 Conversion failed when converting the varchar value ‘CR AZY’ to data type int. Code ———- CM8 3BY G2 9AG W6 8JB |

Listing 5: Single batch using separate INSERT statements with a type conversion error (XACT_ABORT OFF)

You’ll probably notice that execution of the first batch stopped when the conversion error was detected, and just that statement was rolled back. It never found the Unique Constraint error. Then the following batch…select * from PostCode…was executed.

You can combine several statements into a unit of work using wither explicit transactions or by setting implicit transactions on. The latter requires fewer statements but is less versatile and doesn’t provide anything new, so we’ll just stick to explicit transactions

So let’s introduce an explicit transaction that encompasses several statements. We can then see what difference this makes to the behavior we’ve seen with autoCommit.

Explicit Transactions

When we explicitly declare the start of a transaction in SQL by using the BEGIN TRANSACTION statement, we are defining a point at which the data referenced by a particular connection is logically and physically consistent. If errors are encountered, all data modifications made after the BEGIN TRANSACTION can be rolled back to return the data to this known state of consistency. While it’s possible to get SQL Server to roll back in this fashion, it doesn’t do it without additional logic. We either have to specify this behavior by setting XACT_ABORT to ON, so that the explicit transaction is rolled back automatically, or by using a ROLLBACK.

Many developers believe that the mere fact of having declared the start of a transaction is enough to trigger an automatic rollback of the entire transaction if we hit an error during that transaction. Let’s try it.

|

SET XACT_ABORT OFF DELETE FROM PostCode BEGIN TRANSACTION INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR AZY’; —invalid PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; —a duplicate. Not allowed COMMIT TRANSACTION go SELECT * FROM PostCode; |

Listing 6: Multi-statement INSERT (single batch) using an explicit transaction

No dice. The result is exactly the same as when we tried it without the explicit transaction (see Listing 3). If we again use SET XACT_ABORT ON then the batch is again aborted at the first error, but this time, the whole unit of work is rolled back.

By using SET XACT_ABORT ON, you make SQL Server do what most programmers think happens anyway. Since it is unusual not to want to rollback a transaction following an error, it is normally safer to explicitly set it ON. However, there are times when you’d want it OFF. You might, for example, wish to know about every constraint violation in the rows being imported into a table, and then do a complete rollback if any errors happened.

Most SQL Server clients set it to OFF by default, though OLEDB sets it to ON.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

SET XACT_ABORT OFF DELETE FROM PostCode DECLARE @Error INT SELECT @Error = 0 BEGIN TRANSACTION INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’; SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’; SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR AZY’; —invalid PostCode SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; —a duplicate. Not allowed SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; IF @error > 0 ROLLBACK TRANSACTION else COMMIT TRANSACTION go SELECT * FROM PostCode; SELECT @@Trancount —to check that the transaction is done Msg 547, Level 16, State 0, Line 11 The INSERT statement conflicted with the CHECK constraint «CK__PostCode__Code__4AB81AF0«. The conflict occurred in database «contacts«, table «dbo.PostCode«, column ‘Code’. The statement has been terminated. (1 row(s) affected) Msg 2627, Level 14, State 1, Line 15 Violation of PRIMARY KEY constraint ‘PK__PostCode__A25C5AA648CFD27E’. Cannot insert duplicate key in object ‘dbo.PostCode’. The statement has been terminated. Code ———- |

Listing 7: Multi-statement INSERT (single batch) using an explicit transaction

In this batch, we execute all the insertions in separate statements, checking the volatile @@Error value. Then, we check to see whether the batch hit errors or it was successful. If it completes without any errors, we issue a COMMIT TRANSACTION to make the modification a permanent part of the database. If one or more errors are encountered, then all modifications are undone with a ROLLBACK TRANSACTION statement that rolls back to the start of the transaction.

The use of @@Error isn’t entirely pain-free, since it only records the last error, and so, if a trigger has fired after the statement you’re checking, then the @@Error value will be that corresponding to the last statement executed in the trigger, rather than your statement.

If the transaction becomes doomed, all that happens is that the transaction is rolled back without the rest of the transaction being executed, just as would happen anyway if XACT_ABORT is set to ON.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

SET XACT_ABORT OFF DELETE FROM PostCode DECLARE @Error INT SELECT @Error = 0 BEGIN TRANSACTION INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’; SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’; SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR AZY’; —invalid PostCode SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’+1; —a duplicate. Not allowed SELECT @Error = @error + @@error; IF @error > 0 ROLLBACK TRANSACTION else COMMIT TRANSACTION go SELECT * FROM PostCode; SELECT @@Trancount; —to check that the transaction is complete Msg 245, Level 16, State 1, Line 6 Conversion failed when converting the varchar value ‘W6 8JB’ to data type int. Code ———- |

Listing 8: Multi-statement INSERT (single batch) with a doomed explicit transaction

There is a problem with this code, because I’ve issued the rollback without any qualification. If this code is called from within another transaction is will roll back to the start of the outer transaction. Often this is not what you want. I should really have declared a SavePoint to specify where to rollback to. I must explain.

Nested transactions and Savepoints

Transactions can be misleading because programmers equate them to program blocks, and assume that they can somehow be ‘nested’. All manner of routines can be called during a transaction, and some of them could, in turn, specify a transaction, but a rollback will always go to the base transaction.

Support for nested transactions in SQL Server (or other RDBMSs) simply means that it will tolerate us embedding a transaction within one or more other transactions. Most developers will assume that such ‘nesting’ will ensure that SQL Server handles each sub-transaction in an atomic way, as a logical unit of work that can commit independently of other child transactions. However, such behavior is not possible with nested transactions in SQL Server, or other RDMBSs; if the outer transaction was to allow such a thing it would be subverting the all-or-nothing rule of atomicity. SQL Server allows transactions within transactions purely so that a process can call transactions within a routine, such as a stored procedure, regardless of whether that process is within a transaction.

The use of a SavePoint can, however, allow you to rollback a series of statements within a transaction.

Without a Savepoint, a ROLLBACK of a nested transaction can affect more than just the unit of work we’ve defined . If we rollback a transaction and it is ‘nested’ within one or more other transactions, it doesn’t just roll back to the last, or innermost BEGIN TRANSACTION, but rolls all the way back in time to the start of the base transaction. This may not be what we want or expect, and could turn a minor inconvenience into a major muddle.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

SET XACT_ABORT OFF DELETE FROM PostCode DECLARE @Error INT SELECT @Error = 0 BEGIN TRANSACTION INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’; BEGIN TRANSACTION —‘nested’ transaction INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘BY 5JR’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘PH2 0QA’; ROLLBACK—end of ‘nesting’ INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR 4ZY’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; COMMIT TRANSACTION go SELECT * FROM PostCode; SELECT @@Trancount; —to check that the transaction is complete Msg 3902, Level 16, State 1, Line 15 The COMMIT TRANSACTION request has no corresponding BEGIN TRANSACTION. Code ———- CR 4ZY G2 9AG |

Listing 9: Rolling back a nested transaction without a Savepoint

As you can see, SQL Server hasn’t just rolled back the inner transaction but all the work done since the outer BEGIN TRANSACTION. You have a warning as well, 'The COMMIT TRANSACTION request has no corresponding BEGIN TRANSACTION‘ because the transaction count became zero after the rollback, it successfully inserted two rows and came to the COMMIT TRANSACTION statement.

Similarly, SQL Server simply ignores all commands to COMMIT the transaction within ‘nested’ transactions until the batch issues the COMMIT that matches the outermost BEGIN TRANSCATION.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

SET XACT_ABORT OFF DELETE FROM PostCode DECLARE @Error INT SELECT @Error = 0 BEGIN TRANSACTION INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’; BEGIN TRANSACTION —‘nested’ transaction INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘BY 5JR’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘PH2 0QA’; COMMIT TRANSACTION—end of ‘nesting’ INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR 4ZY’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; Rollback go SELECT * FROM PostCode; SELECT @@Trancount; —to check that the transaction is complete Code ———- |

Listing 10: Attempting to COMMIT a nested transaction without a Savepoint

The evident desire was to commit the nested transaction, because we explicitly requested that the changes in the transaction be made permanent, and so we might expect at least something to happen, but what does? Nothing; if we have executed a COMMIT TRANSACTION in a nested transaction that is contained a parent transaction that is then rolled back, the nested transaction will also be rolled back. SQL Server ignores the nested COMMIT command and, whatever we do, nothing is committed until the base transaction is committed. In other words, the COMMIT of the nested transaction is actually conditional on the COMMIT of the parent.

One might think that it is possible to use the NAME parameter of the ROLLBACK TRANSACTION statement to refer to the inner transactions of a set of named ‘nested’ transactions. Nice try, but the only name allowed, other than a Savepoint, is the transaction name of the outermost transaction. By adding the name, we can specify that all of the nested transactions are rolled back leaving the outermost, or ‘base’, one, whereas if we leave it out then the rollback includes the outermost transaction. The NAME parameter is only useful in that we’ll get an error if someone inadvertently wraps what was the base transaction in a new base transaction, By giving the base transaction a name, it makes it easier to identify when we want to monitor the progress of long-running queries.

We can sort this problem out by using a SavePoint. This will allow us to do quite a bit of what we might have thought was happening anyway by nesting transactions! Savepoints are handy for marking a point in your transaction. We then have the option, later, of rolling back work performed before the current point in the transaction but after a declared savepoint within the same transaction.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 |

SET XACT_ABORT OFF DELETE FROM PostCode DECLARE @Error INT SELECT @Error = 0 BEGIN TRANSACTION INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’; SAVE TRANSACTION here —create a savepoint called ‘here’ INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘BY 5JR’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘PH2 0QA’; ROLLBACK TRANSACTION here —rollback to the savepoint INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR 4ZY’; INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; COMMIT TRANSACTION go SELECT * FROM PostCode; SELECT @@Trancount; —to check that the transaction is complete Code ———- CM8 3BY CR 4ZY G2 9AG W6 8JB |

Listing 11: Using Savepoints to roll back to a ‘known’ point

When we roll backto a save point, only those statements that ran after the savepoint are rolled back. All savepoints that were established later are, of course, lost.

So, if we actually want rollback within a nested transaction , then we can create a savepoint at the start. Then, if a statement within the transaction fails, it is easy to return the data to its state before the transaction began and re-run it. Even better, we can create a transaction and call a series of stored procedures which do DML stuff. Before each stored procedure, we can create a savepoint. Then, if the procedure fails, it is easy to return the data to its state before it began and re-run the function with revised parameters or set to perform a recovery action. The downside would be holding a transaction open for too long.

The Consequences of Errors.

In our example, we’re dealing mainly with constraint violations which lead to statement termination, and we’ve contrasted them to errors that lead to batch abortion, and demonstrated that by setting XACT_ABORT ON, statement termination starts to behave more like batch-abortion errors. (‘scope-abortion’ happens when there is a compile error, ‘connection-termination’ only happens when something horrible happens, and ‘batch-cancellation’ only when the client of a session cancels it, or there is a time-out ) All this can be determined from the @@Error variable but there is nothing one can do to prevent errors from being passed back to the application. Nothing, that is, unless you use TRY...CATCH

TRY CATCH Behavior

It is easy to think that all one’s troubles are over with TRY..CATCH, but in fact one still needs to be aware of other errors

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 |

set XACT_ABORT on DELETE FROM PostCode BEGIN TRY INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’ AS PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR AZY’ —‘CR1 4ZY’ for a valid one INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’ INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; END TRY BEGIN CATCH PRINT ‘ERROR ‘ + CONVERT(VARCHAR(8), @@error) + ‘, ‘ + ERROR_MESSAGE() END CATCH; SELECT * FROM PostCode ERROR 547 The INSERT statement conflicted with the CHECK constraint «CK__PostCode__Code__44FF419A«. The conflict occurred in database «contacts«, table «dbo.PostCode«, column ‘Code’. (1 row(s) affected) ERROR Code ———- CM8 3BY W6 8JB (2 row(s) affected) |

Listing 12: TRY…CATCH without a transaction

This behaves the same way whether XACT_ABORT is on or off. This catches the first execution error that has a severity higher than 10 that does not close the database connection. This means that execution ends after the first error, but there is no automatic rollback of the unit of work defined by the TRY block: No, we must still define a transaction. This works fine for most purposes though one must beware of the fact that certain errors such as killed connections or timeouts don’t get caught.

Try-Catch behavior deals with statement termination but needs extra logic to deal well with batch-abortion. In other words, we need to deal with un-committable and doomed transactions. Here is what happens if we don’t do it properly.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 |

set XACT_ABORT on DELETE FROM PostCode BEGIN TRANSACTION SAVE TRANSACTION here —only if SET XACT_ABORT OFF BEGIN TRY INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’ AS PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR AZY’ —‘CR1 4ZY’ for a valid one INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’ INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; END TRY BEGIN CATCH ROLLBACK TRANSACTION here PRINT ‘ERROR ‘ + CONVERT(VARCHAR(8), @@error) + ‘, ‘ + ERROR_MESSAGE()END CATCH; SELECT * FROM PostCode) Msg 3931, Level 16, State 1, Line 16 The current transaction cannot be committed and cannot be rolled back to a savepoint. Roll back the entire transaction. |

Listing 13: Mishandled Batch-abort

This error will immediately abort and roll back the batch whatever you do, but the TRY-CATCH seems to handle the problem awkwardly if you set XACT_ABORT ON, and it passes back a warning instead of reporting the error. Any error causes the transaction to be classified as an un-committable or ‘doomed’ transaction. The request cannot be committed, or rolled back to a savepoint. Only a full rollback to the start of the base transaction will do. No write operations can happen until it rolls back the transaction, only reads.

If you set XACT_ABORT off, then it behaves gracefully, but terminates after the first error it comes across, executing the code in the CATCH block.

To get around this, we can use the XACT_STATE() function. This will tell you whether SQL Server has determined that the transaction is doomed. Whilst we can use the @@TRANCOUNT variable to detect whether the current request has an active user transaction, we cannot use it to determine whether that transaction has been classified as an uncommitable transaction. Only XACT_STATE() will tell us if the transaction is doomed, and only only @@TRANCOUNT can be used to determine whether there are nested transactions.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

set XACT_ABORT off Declare @xact_state int DELETE FROM PostCode BEGIN TRANSACTION SAVE TRANSACTION here —only if SET XACT_ABORT OFF BEGIN TRY INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘W6 8JB’ AS PostCode INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ INSERT INTO PostCode (code) SELECT ‘CR 4ZY’ —‘CR1 4ZY’ for a valid one INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’ INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT ‘G2 9AG’; END TRY BEGIN CATCH select @xact_state=XACT_STATE() IF ( @xact_state ) = 1 —the transaction is commitable ROLLBACK TRANSACTION here —just rollback to the savepoint ELSE ROLLBACK TRANSACTION —back to base, because it’s probably doomed PRINT case when @xact_state= —1 then ‘Doomed ‘ else » end +‘Error ‘ + CONVERT(VARCHAR(8), ERROR_NUMBER()) + ‘ on line ‘ + CONVERT(VARCHAR(8), ERROR_LINE()) + ‘, ‘ + ERROR_MESSAGE() END CATCH; IF XACT_STATE() = 1 COMMIT TRANSACTION —only if this is the base transaction —only if it hasn’t been rolled back SELECT * FROM PostCode |

Listing 14: Both Statement-termination and Batch abort handled

Reaching the Goal

So now, we can have reasonable confidence that we have a mechanism that will allow us to import a large number of records and tell us, without triggering errors, which records contain bad data, as defined by our constraints.

Sadly, we are going to do this insertion row-by-row, but you’ll see that 10,000 rows only takes arount three seconds, so it is worth the wait. We have a temporary table full of 10,000 valid PostCodes, and we’ll add in a couple of rogues just to test out what happens.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

SET XACT_ABORT OFF DELETE FROM PostCode SET NOCOUNT ON DECLARE @II INT, @iiMax INT, @Code VARCHAR(10) DECLARE @TemporaryStagingTable TABLE (Code_ID INT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY, Code CHAR(10) ) DECLARE @Error TABLE (Error_ID INT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY, ErrorCode INT, PostCodeVARCHAR(10), TransactionState INT, ErrorMessage VARCHAR(255) ) INSERT INTO @TemporaryStagingTable (code) SELECT code FROM PostCodeData UNION ALL SELECT ‘W6 8JB’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘CR AZY’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘G2 9AG’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘G2 9AG’ SELECT @ii=MIN(Code_ID),@iiMax=MAX(Code_ID) FROM @TemporaryStagingTable WHILE @ii<=@iiMax BEGIN BEGIN try SELECT @Code=code FROM @TemporaryStagingTable WHERE Code_ID=@ii INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT @Code END try BEGIN CATCH INSERT INTO @error(ErrorCode, PostCode,TransactionState,ErrorMessage) SELECT ERROR_NUMBER(), @Code, XACT_STATE(), ERROR_MESSAGE() END CATCH; SELECT @ii=@ii+1 END SELECT * FROM @error |

Listing 15: insert from staging table with error reporting but without rollback on error

..and if you wanted to rollback the whole import process if you hit an error, then you could try this.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 |

SET XACT_ABORT OFF —to get statement-level rollbacks DELETE FROM PostCode—teardown last test SET NOCOUNT ON DECLARE @II INT, @iiMax INT, @Code VARCHAR(10) DECLARE @TemporaryStagingTable TABLE —to help us iterate through (Code_ID INT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY, Code CHAR(10) ) DECLARE @Error TABLE —to collect up all the errors (Error_ID INT IDENTITY(1,1) PRIMARY KEY, ErrorCode INT, PostCodeVARCHAR(10), TransactionState INT, ErrorMessage VARCHAR(255) ) INSERT INTO @TemporaryStagingTable (code) SELECT code FROM PostCodeData —the good stuff UNION ALL SELECT ‘W6 8JB’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘CM8 3BY’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘CR AZY’ UNION ALL SELECT ‘G2 9AG’ —bad stuff UNION ALL SELECT ‘G2 9AG’ —bad stuff —get the size of the table SELECT @ii=MIN(Code_ID),@iiMax=MAX(Code_ID) FROM @TemporaryStagingTable BEGIN TRANSACTION —start a transaction SAVE TRANSACTION here —pop in a savepoint since we may already be in a transaction —and we don’t want to mess it up WHILE @ii <= @iiMax AND XACT_STATE() <> —1 —if the whole transaction is doomed —then you’ve no option BEGIN BEGIN try —get the code first for our error record SELECT @Code=code FROM @TemporaryStagingTable WHERE Code_ID=@ii INSERT INTO PostCode(code) SELECT @Code —pop it in END try BEGIN CATCH —record the error INSERT INTO @error(ErrorCode, PostCode,TransactionState,ErrorMessage) SELECT ERROR_NUMBER(), @Code, XACT_STATE(), ERROR_MESSAGE() END CATCH; SELECT @ii=@ii+1 END IF EXISTS (SELECT * FROM @error) BEGIN IF ( XACT_STATE() ) = 1 —the transaction is commitable ROLLBACK TRANSACTION here —just rollback to the savepoint ELSE ROLLBACK TRANSACTION —we’re doomed! Doomed! SELECT * FROM @error; END ELSE COMMIT |

Listing 16: insert from staging table with error-reporting and rollback on error

You can comment out the rogue PostCodes or change the XACT_ABORT settings just to check if it handles batch aborts properly.

Conclusion

To manage transactions properly, and react appropriately to errors fired by constraints, you need to plan carefully. You need to distinguish the various types of errors, and make sure that you react to all of these types appropriately in your code, where it is possible to do so. You need to specify the transaction abort mode you want, and the transaction mode, and you should monitor the transaction level and transaction state.

You should be clear that transactions are never nested, in the meaning that the term usually conveys.

Transactions must be short, and only used when necessary. A session must always be cleaned up, even when it times-out or is aborted, and one must do as much error reporting as possible when transactions have to be rolled back. DDL changes should be avoided within transactions, so as to avoid locks being placed on system tables.

The application developer should be not be forced to become too familiar with SQL Server errors, though some will inevitably require handling within application code. As much as possible, especially in the case of moderate errors such as constraint violations or deadlocks should be handled within the application/database interface.

Once the handling of constraint errors within transactions has been tamed and understood, constraints will prove to be one of the best ways of guaranteeing the integrity of the data within a database.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Problem

- Solution

- Custom Error Table

- Naming Convention

- Conclusion

- See Also

- See Also

Introduction

In the former article about CHECK constraints, we did not cover how to handle the errors when a CHECK constraint violates. In this article, we cover this important topic. It has worth to take a look at

that article, if it needed. All Code samples in this article are downloadable from this

link.

Problem

We can rapidly jump into the main problem using a sample. Assuming that we have a Book table that has two date columns one for writing date and other for publish date. We want to apply a date validator to avoid inserting the writing

dates that are greater than publish date in each row using the next code:

IF OBJECT_ID('dbo.book',

'u') IS

NOT NULL

DROPTABLE

dbo.Book

go

CREATE

TABLE

dbo.Book

(

BookId

INT

NOTNULL ,

WritingDate

DATE

NULL,

publishDate

DATE

NULL,

CONSTRAINT

Pk_Book PRIMARY

KEY

CLUSTERED ( BookId ASC

)

)

GO

ALTER

TABLE

dbo.Book WITH

CHECK

ADD

CONSTRAINT

DateValidator CHECK

( WritingDate > publishDate )

GO

Now, we can test what will happen if the violation occurs. To do this, we can use the next code and we will face with an error message like the following image:

INSERT

dbo.Book

( BookId, WritingDate, publishDate )

VALUES

( 1, GETDATE(), GETDATE() + 1 )

Solution

As illustrated in the above picture, the error message is not so clear. It is good to know that error happened on which object, but with no reason. We can use two workaround to make it clearer.

Custom Error Table

As it is it highlighted in yellow color in the above picture, whenever a CHECK constraint violates we get the same error message number that is 547. We can use this error number, send it to a function that can make a good error

message. In the error message that sows in the above picture, we can see that we have another great pretext which is the own CHECK constraint name which is unique in the whole database. All these information lead us to use a user table that helps us to create

good messages. We can start doing this by the next code:

CREATE

TABLE

CustomError

(

ObjectName NVARCHAR(128)

PRIMARY

KEY,

ErrorMessage NVARCHAR(4000)

);

GO

INSERT

dbo.CustomError

VALUES

( N'DateValidator',

N'Writing date must be greater than publish date.'

) ;

In the above code, we also insert a new good message as equivalent to constraint name. Now we can write a function to use the good message whenever the error occurs. One simple implementation is like the next code. You can change

it as you wish to fit your requirements:

CREATE

FUNCTION

dbo.ufnGetClearErrorMessage1()

RETURNS

NVARCHAR(4000)

AS

BEGIN

DECLARE

@Msg NVARCHAR(4000) = ERROR_MESSAGE() ;

DECLARE

@ErrNum INT

= ERROR_NUMBER() ;

DECLARE

@ClearMessage NVARCHAR(4000) ;

IF @ErrNum = 547

BEGIN

/*--how to find constraint name:

SELECT

CHARINDEX('"', @Msg) ,

CHARINDEX('.', @Msg) ,

RIGHT(@Msg,LEN(@Msg) - CHARINDEX('"',

@Msg)) ,

LEFT(RIGHT(@Msg,LEN(@Msg)

- CHARINDEX('"', @Msg)), CHARINDEX('"',

RIGHT(@Msg,LEN(@Msg) - CHARINDEX('"', @Msg))) - 1)

*/

DECLARE

@ObjectName NVARCHAR(128)

SELECT

@ObjectName = LEFT(RIGHT(@Msg,LEN(@Msg) - CHARINDEX('"',

@Msg)), CHARINDEX('"',

RIGHT(@Msg,LEN(@Msg) - CHARINDEX('"', @Msg))) - 1)

SELECT

@ClearMessage = @Msg + CHAR(13) + ce.ErrorMessage

FROM

dbo.CustomError AS

ce

WHERE

ce.ObjectName = @ObjectName ;

END

ELSE

SET

@ClearMessage = @Msg ;

RETURN

@ClearMessage ;

END

Now, we can use this function to get the good message. The next code shows how to use this function in our code:

BEGIN

TRY

INSERT

dbo.Book

( BookId, WritingDate, publishDate )

VALUES

( 1, GETDATE(), GETDATE() + 1 )

END

TRY

BEGIN

CATCH

DECLARE

@Msg NVARCHAR(4000) = dbo.ufnGetClearErrorMessage1();

THROW 60001, @Msg, 1;

END

CATCH

Naming Convention

Other solution is using a specific naming convention. Like the previous solution we can use the error number to identify that the error occurred when a CHECK constraint violated. But in this solution we will use a naming convention

instead of using a user error table. Again, we create a function to clear the error message. We could use many user defined conventions. But in this article we see one sample and of course you can create your own one. The following code changes the CHECK constraint

name to new one:

--drop old CHECK constraint

ALTER

TABLE

dbo.Book

DROP

CONSTRAINT

DateValidator

GO

--add new CHECK constraint

ALTER

TABLE

dbo.Book WITH

CHECK

ADD

CONSTRAINT

C_Book_@Writing_date_must_be_greater_than_publish_date CHECK

( WritingDate > publishDate )

GO

Now, we can create a new function that will fix the error message based on the characters after the @-sign character and replaces the underline characters with space characters to make it a meaningful and readable error message.

It is obvious that this is a user defined naming convention that have to be used in the whole database for all CHECK constraints implemented by all developers. The next code creates this function:

CREATE

FUNCTION

dbo.ufnGetClearErrorMessage2()

RETURNS

NVARCHAR(4000)

AS

BEGIN

DECLARE

@Msg NVARCHAR(4000) = ERROR_MESSAGE() ;

DECLARE

@ErrNum INT

= ERROR_NUMBER() ;

DECLARE

@ClearMessage NVARCHAR(4000) ;

IF @ErrNum = 547

BEGIN

/*--how to find @ClearMessage:

SELECT

@msg ,

CHARINDEX('@', @msg) ,

RIGHT(@msg, LEN(@msg) - CHARINDEX('@',

@msg)) ,

CHARINDEX('"',

RIGHT(@msg, LEN(@msg) - CHARINDEX('@', @msg))) ,

LEFT(RIGHT(@msg,

LEN(@msg) - CHARINDEX('@', @msg)), CHARINDEX('"',

RIGHT(@msg, LEN(@msg) - CHARINDEX('@', @msg))) - 1 ) ,

REPLACE(LEFT(RIGHT(@msg,

LEN(@msg) - CHARINDEX('@', @msg)), CHARINDEX('"',

RIGHT(@msg, LEN(@msg) - CHARINDEX('@', @msg))) - 1 ),

'_', SPACE(1)) +

'.'

*/

SELECT

@ClearMessage = @Msg + CHAR(13) +

REPLACE(LEFT(RIGHT(@msg,

LEN(@msg) - CHARINDEX('@', @msg)), CHARINDEX('"',

RIGHT(@msg, LEN(@msg) - CHARINDEX('@', @msg))) - 1 ),

'_', SPACE(1)) +

'.'

END

ELSE

SET

@ClearMessage = @Msg ;

RETURN

@ClearMessage ;

END

Now, we can use this function to get the good message. The next code shows how to use this function in our code:

BEGIN

TRY

INSERT

dbo.Book

( BookId, WritingDate, publishDate )

VALUES

( 1, GETDATE(), GETDATE() + 1 )

END

TRY

BEGIN

CATCH

DECLARE

@Msg NVARCHAR(4000) = dbo.ufnGetClearErrorMessage2();

THROW 60001, @Msg, 1;

END

CATCH

Conclusion

Using these two solutions makes the error message clearer. Such good error messages tell us why it occurs in addition to where it happens. Moreover, we can use stored procedures instead of using functions.

See Also

- Transact-SQL Portal

- T-SQL: CHECK Constraints

- Structured Error Handling Mechanism in SQL Server 2012

Finding out why Foreign key creation fail

When MySQL is unable to create a Foreign Key, it throws out this generic error message:

ERROR 1215 (HY000): Cannot add foreign key constraint

– The most useful error message ever.

Fortunately, MySQL has this useful command that can give the actual reason about why it could not create the Foreign Key.

mysql> SHOW ENGINE INNODB STATUS;That will print out lots of output but the part we are interested in is under the heading ‘LATEST FOREIGN KEY ERROR’:

------------------------ LATEST FOREIGN KEY ERROR ------------------------ 2020-08-29 13:40:56 0x7f3cb452e700 Error in foreign key constraint of table test_database/my_table: there is no index in referenced table which would contain the columns as the first columns, or the data types in the referenced table do not match the ones in table. Constraint: , CONSTRAINTidx_nameFOREIGN KEY (employee_id) REFERENCESemployees(id) The index in the foreign key in table isidx_namePlease refer to http://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/5.7/en/innodb-foreign-key-constraints.html for correct foreign key definition.

This output could give you some clue about the actual reason why MySQL could not create your Foreign Key

Reason #1 – Missing unique index on the referenced table

This is probably the most common reason why MySQL won’t create your Foreign Key constraint. Let’s look at an example with a new database and new tables:

In the all below examples, we’ll use a simple ‘Employee to Department” relationship:

mysql> CREATE DATABASE foreign_key_1;

Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec)mysql> USE foreign_key_1;

Database changed

mysql> CREATE TABLE employees(

-> id int,

-> name varchar(20),

-> department_id int

-> );

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.08 sec)

mysql> CREATE TABLE departments(

-> id int,

-> name varchar(20)

-> );

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.07 sec)As you may have noticed, we have not created the table with PRIMARY KEY or unique indexes. Now let’s try to create Foreign Key constraint between employees.department_id column and departments.id column:

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

ERROR 1215 (HY000): Cannot add foreign key constraintLet’s look at the detailed error:

mysql> SHOW ENGINE INNODB STATUS;------------------------ LATEST FOREIGN KEY ERROR ------------------------ 2020-08-31 09:25:13 0x7fddc805f700 Error in foreign key constraint of table foreign_key_1/#sql-5ed_49b: FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id): Cannot find an index in the referenced table where the referenced columns appear as the first columns, or column types in the table and the referenced table do not match for constraint. Note that the internal storage type of ENUM and SET changed in tables created with >= InnoDB-4.1.12, and such columns in old tables cannot be referenced by such columns in new tables. Please refer to http://dev.mysql.com/doc/refman/5.7/en/innodb-foreign-key-constraints.html for correct foreign key definition.

This is because we don’t have any unique index on the referenced table i.e. departments. We have two ways of fixing this:

Option 1: Primary Keys

Let’s fix this by adding a primary key departments.id

mysql> ALTER TABLE departments ADD PRIMARY KEY (id);

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.20 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.19 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0Option 2: Unique Index

mysql> CREATE UNIQUE INDEX idx_department_id ON departments(id);

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.13 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.21 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0Reason #2 – Different data types on the columns

MySQL requires the columns involved in the foreign key to be of the same data types.

mysql> CREATE DATABASE foreign_key_1;

Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec)

mysql> USE foreign_key_1;

Database changed

mysql> CREATE TABLE employees(

-> id int,

-> name varchar(20),

-> department_id int,

-> PRIMARY KEY (id)

-> );

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.06 sec)

mysql> CREATE TABLE departments(

-> id char(20),

-> name varchar(20),

-> PRIMARY KEY (id)

-> );

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.07 sec)You may have noticed that employees.department_id is int while departments.id is char(20). Let’s try to create a foreign key now:

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

ERROR 1215 (HY000): Cannot add foreign key constraintLet’s fix the type of departments.id and try to create the foreign key again:

mysql> ALTER TABLE departments MODIFY id INT;

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.18 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.26 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0It works now!

Reason #3 – Different collation/charset type on the table

This is a surprising reason and hard to find out. Let’s create two tables with different collation (or also called charset):

Let’s start from scratch to explain this scenario:

mysql> CREATE DATABASE foreign_key_1; Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec)

mysql> USE foreign_key_1; Database changed

mysql> CREATE TABLE employees(

-> id int,

-> name varchar(20),

-> department_id int,

-> PRIMARY KEY (id)

-> ) ENGINE=InnoDB CHARACTER SET=utf8;

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.06 sec)

mysql> CREATE TABLE departments(

-> id int,

-> name varchar(20),

-> PRIMARY KEY (id)

-> ) ENGINE=InnoDB CHARACTER SET=latin1;

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.08 sec)You may notice that we are using a different character set (utf8 and latin1` for both these tables. Let’s try to create the foreign key:

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

ERROR 1215 (HY000): Cannot add foreign key constraintIt failed because of different character sets. Let’s fix that.

mysql> SET foreign_key_checks = 0; ALTER TABLE departments CONVERT TO CHARACTER SET utf8 COLLATE utf8_general_ci; SET foreign_key_checks = 1;

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec)

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.18 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec)

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.20 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0If you have many tables with a different collation/character set, use this script to generate a list of commands to fix all tables at once:

mysql --database=your_database -B -N -e "SHOW TABLES" | awk '{print "SET foreign_key_checks = 0; ALTER TABLE", $1, "CONVERT TO CHARACTER SET utf8 COLLATE utf8_general_ci; SET foreign_key_checks = 1; "}'Reason #4 – Different collation types on the columns

This is a rare reason, similar to reason #3 above but at a column level.

Let’s try to reproduce this from scratch:

mysql> CREATE DATABASE foreign_key_1; Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec)

mysql> USE foreign_key_1; Database changed

mysql> CREATE TABLE employees(

-> id int,

-> name varchar(20),

-> department_id char(26) CHARACTER SET utf8,

-> PRIMARY KEY (id)

-> );

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.07 sec)

mysql> CREATE TABLE departments(

-> id char(26) CHARACTER SET latin1,

-> name varchar(20),

-> PRIMARY KEY (id)

-> );

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.08 sec)We are using a different character set for employees.department_id and departments.id (utf8 and latin1). Let’s check if the Foreign Key can be created:

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

ERROR 1215 (HY000): Cannot add foreign key constraintNope, as expected. Let’s fix that by changing the character set of departments.id to match with employees.department_id:

mysql> ALTER TABLE departments MODIFY id CHAR(26) CHARACTER SET utf8;

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.20 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.20 sec)

Records: 0 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0It works now!

Reason #5 -Inconsistent data

This would be the most obvious reason. A foreign key is to ensure that your data remains consistent between the parent and the child table. So when you are creating the foreign key, the existing data is expected to be already consistent.

Let’s setup some inconsistent data to reproduce this problem:

mysql> CREATE DATABASE foreign_key_1; Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec)

mysql> USE foreign_key_1; Database changed

mysql> CREATE TABLE employees(

-> id int,

-> name varchar(20),

-> department_id int,

-> PRIMARY KEY (id)

-> );

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.06 sec)

mysql> CREATE TABLE departments(

-> id int,

-> name varchar(20),

-> PRIMARY KEY (id)

-> );

Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.08 sec)Let’s insert a department_id in employees table that will not exist in departments.id:

mysql> INSERT INTO employees VALUES (1, 'Amber', 145);

Query OK, 1 row affected (0.01 sec)Let’s create a foreign key now and see if it works:

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

ERROR 1452 (23000): Cannot add or update a child row: a foreign key constraint fails (`foreign_key_1`.`#sql-5ed_49b`, CONSTRAINT `fk_department_id` FOREIGN KEY (`department_id`) REFERENCES `departments` (`id`))This error message is atleast more useful. We can fix this in two ways. Either by adding the missing department in departments table or by deleting all the employees with the missing department. We’ll do the first option now:

mysql> INSERT INTO departments VALUES (145, 'HR');

Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec)Let’s try to create the Foreign Key again:

mysql> ALTER TABLE employees ADD CONSTRAINT fk_department_id FOREIGN KEY idx_employees_department_id (department_id) REFERENCES departments(id);

Query OK, 1 row affected (0.24 sec)

Records: 1 Duplicates: 0 Warnings: 0It worked this time.

So we have seen 5 different ways a Foreign Key creation can fail and possible solutions of how we can fix them. If you have encountered a reason not listed above, add them in the comments.

If you are using MySQL 8.x, the error message will be a little different:

SQLSTATE[HY000]: General error: 3780 Referencing column 'column' and referenced column 'id' in foreign key constraint 'idx_column_id' are incompatible. I am totally new to SQL Server management, I tried to add a constraint in a table.

The situation is that I created a column with only ‘Y’or ‘N’ allowed to be valued.

So I tried to create a constraint in Management Studio by right clicking «Constraints» in the table.

However, I really have no idea about the syntax of creating a constraint. Finally, I tried to input the code into «Check Constraint Expression» window by referring the template from the Internet. The SQL Server always tell me «Error Validating constaint».

Can you guys just help me to write the first constraint for me? Because I really dont know how to start.

My requirement is:

I have a table called "Customer"

I created a column called "AllowRefund"

The column "AllowRefund" is only allowed to 'Y' or 'N'

Thanks.

asked Nov 2, 2012 at 22:06

0

I’d advise against what you are trying to do. There is a datatype (Bit) that is designed to represent values with two states. If you use this type you won’t even need the constraint at all. SQL Server will enforce the value to be either one or zero with no additonal work required. You just have to design your app to treat 1 as yes, and 0 as No.

The approach you are attempting is just not a good idea and no good will come of it.

answered Nov 2, 2012 at 22:10

JohnFxJohnFx

34.5k18 gold badges104 silver badges162 bronze badges

1

You can do this as follows:

ALTER TABLE Customer

ADD CONSTRAINT CK_Customer_AllowRefund

CHECK (AllowRefund in ('Y','N'))

However @JohnFx is correct — you’d be better off making this column a bit field.

answered Nov 2, 2012 at 22:14

JohnLBevanJohnLBevan

22.5k12 gold badges92 silver badges174 bronze badges

I partly agree with JohnFix, but as knowing the correct syntax to define a check constraint might be useful for you in the future (as you apparently don’t read manuals), here is the SQL to create such a constraint:

alter table customer

add constraint check_yes_no check (AllowRefund in ('Y', 'N'));

You probably want to also define the column as NOT NULL in order to make sure you always have a value for that.

(As I don’t use «Management Studio» I cannot tell you where and how you have to enter that SQL).

answered Nov 2, 2012 at 22:14

1