Tall Arrays

Calculate with arrays that have more rows than fit in memory.

This function fully supports tall arrays. For

more information, see Tall Arrays.

C/C++ Code Generation

Generate C and C++ code using MATLAB® Coder™.

Usage notes and limitations:

-

Strict single-precision calculations are not supported. In the generated code,

single-precision inputs produce single-precision outputs. However, variables inside the

function might be double-precision.

Thread-Based Environment

Run code in the background using MATLAB® backgroundPool or accelerate code with Parallel Computing Toolbox™ ThreadPool.

GPU Arrays

Accelerate code by running on a graphics processing unit (GPU) using Parallel Computing Toolbox™.

This function fully supports GPU arrays. For more information, see Run MATLAB Functions on a GPU (Parallel Computing Toolbox).

Distributed Arrays

Partition large arrays across the combined memory of your cluster using Parallel Computing Toolbox™.

| Error function | |

|---|---|

Plot of the error function |

|

| General information | |

| General definition |  |

| Fields of application | Probability, thermodynamics |

| Domain, Codomain and Image | |

| Domain |  |

| Image |  |

| Basic features | |

| Parity | Odd |

| Specific features | |

| Root | 0 |

| Derivative |  |

| Antiderivative |  |

| Series definition | |

| Taylor series |  |

In mathematics, the error function (also called the Gauss error function), often denoted by erf, is a complex function of a complex variable defined as:[1]

This integral is a special (non-elementary) sigmoid function that occurs often in probability, statistics, and partial differential equations. In many of these applications, the function argument is a real number. If the function argument is real, then the function value is also real.

In statistics, for non-negative values of x, the error function has the following interpretation: for a random variable Y that is normally distributed with mean 0 and standard deviation 1/√2, erf x is the probability that Y falls in the range [−x, x].

Two closely related functions are the complementary error function (erfc) defined as

and the imaginary error function (erfi) defined as

where i is the imaginary unit

Name[edit]

The name «error function» and its abbreviation erf were proposed by J. W. L. Glaisher in 1871 on account of its connection with «the theory of Probability, and notably the theory of Errors.»[2] The error function complement was also discussed by Glaisher in a separate publication in the same year.[3]

For the «law of facility» of errors whose density is given by

(the normal distribution), Glaisher calculates the probability of an error lying between p and q as:

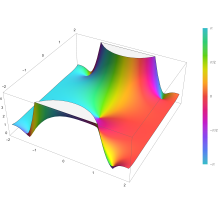

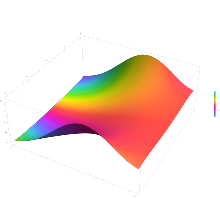

Plot of the error function Erf(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D

Applications[edit]

When the results of a series of measurements are described by a normal distribution with standard deviation σ and expected value 0, then erf (a/σ √2) is the probability that the error of a single measurement lies between −a and +a, for positive a. This is useful, for example, in determining the bit error rate of a digital communication system.

The error and complementary error functions occur, for example, in solutions of the heat equation when boundary conditions are given by the Heaviside step function.

The error function and its approximations can be used to estimate results that hold with high probability or with low probability. Given a random variable X ~ Norm[μ,σ] (a normal distribution with mean μ and standard deviation σ) and a constant L < μ:

where A and B are certain numeric constants. If L is sufficiently far from the mean, specifically μ − L ≥ σ√ln k, then:

so the probability goes to 0 as k → ∞.

The probability for X being in the interval [La, Lb] can be derived as

Properties[edit]

Integrand exp(−z2)

erf z

The property erf (−z) = −erf z means that the error function is an odd function. This directly results from the fact that the integrand e−t2 is an even function (the antiderivative of an even function which is zero at the origin is an odd function and vice versa).

Since the error function is an entire function which takes real numbers to real numbers, for any complex number z:

where z is the complex conjugate of z.

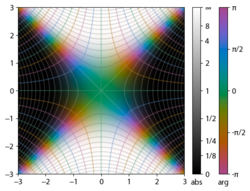

The integrand f = exp(−z2) and f = erf z are shown in the complex z-plane in the figures at right with domain coloring.

The error function at +∞ is exactly 1 (see Gaussian integral). At the real axis, erf z approaches unity at z → +∞ and −1 at z → −∞. At the imaginary axis, it tends to ±i∞.

Taylor series[edit]

The error function is an entire function; it has no singularities (except that at infinity) and its Taylor expansion always converges, but is famously known «[…] for its bad convergence if x > 1.»[4]

The defining integral cannot be evaluated in closed form in terms of elementary functions, but by expanding the integrand e−z2 into its Maclaurin series and integrating term by term, one obtains the error function’s Maclaurin series as:

which holds for every complex number z. The denominator terms are sequence A007680 in the OEIS.

For iterative calculation of the above series, the following alternative formulation may be useful:

because −(2k − 1)z2/k(2k + 1) expresses the multiplier to turn the kth term into the (k + 1)th term (considering z as the first term).

The imaginary error function has a very similar Maclaurin series, which is:

which holds for every complex number z.

Derivative and integral[edit]

The derivative of the error function follows immediately from its definition:

From this, the derivative of the imaginary error function is also immediate:

An antiderivative of the error function, obtainable by integration by parts, is

An antiderivative of the imaginary error function, also obtainable by integration by parts, is

Higher order derivatives are given by

where H are the physicists’ Hermite polynomials.[5]

Bürmann series[edit]

An expansion,[6] which converges more rapidly for all real values of x than a Taylor expansion, is obtained by using Hans Heinrich Bürmann’s theorem:[7]

where sgn is the sign function. By keeping only the first two coefficients and choosing c1 = 31/200 and c2 = −341/8000, the resulting approximation shows its largest relative error at x = ±1.3796, where it is less than 0.0036127:

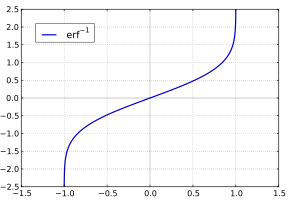

Inverse functions[edit]

Given a complex number z, there is not a unique complex number w satisfying erf w = z, so a true inverse function would be multivalued. However, for −1 < x < 1, there is a unique real number denoted erf−1 x satisfying

The inverse error function is usually defined with domain (−1,1), and it is restricted to this domain in many computer algebra systems. However, it can be extended to the disk |z| < 1 of the complex plane, using the Maclaurin series

where c0 = 1 and

So we have the series expansion (common factors have been canceled from numerators and denominators):

(After cancellation the numerator/denominator fractions are entries OEIS: A092676/OEIS: A092677 in the OEIS; without cancellation the numerator terms are given in entry OEIS: A002067.) The error function’s value at ±∞ is equal to ±1.

For |z| < 1, we have erf(erf−1 z) = z.

The inverse complementary error function is defined as

For real x, there is a unique real number erfi−1 x satisfying erfi(erfi−1 x) = x. The inverse imaginary error function is defined as erfi−1 x.[8]

For any real x, Newton’s method can be used to compute erfi−1 x, and for −1 ≤ x ≤ 1, the following Maclaurin series converges:

where ck is defined as above.

Asymptotic expansion[edit]

A useful asymptotic expansion of the complementary error function (and therefore also of the error function) for large real x is

where (2n − 1)!! is the double factorial of (2n − 1), which is the product of all odd numbers up to (2n − 1). This series diverges for every finite x, and its meaning as asymptotic expansion is that for any integer N ≥ 1 one has

where the remainder, in Landau notation, is

as x → ∞.

Indeed, the exact value of the remainder is

which follows easily by induction, writing

and integrating by parts.

For large enough values of x, only the first few terms of this asymptotic expansion are needed to obtain a good approximation of erfc x (while for not too large values of x, the above Taylor expansion at 0 provides a very fast convergence).

Continued fraction expansion[edit]

A continued fraction expansion of the complementary error function is:[9]

Integral of error function with Gaussian density function[edit]

which appears related to Ng and Geller, formula 13 in section 4.3[10] with a change of variables.

Factorial series[edit]

The inverse factorial series:

converges for Re(z2) > 0. Here

zn denotes the rising factorial, and s(n,k) denotes a signed Stirling number of the first kind.[11][12]

There also exists a representation by an infinite sum containing the double factorial:

Numerical approximations[edit]

Approximation with elementary functions[edit]

- Abramowitz and Stegun give several approximations of varying accuracy (equations 7.1.25–28). This allows one to choose the fastest approximation suitable for a given application. In order of increasing accuracy, they are:

(maximum error: 5×10−4)

where a1 = 0.278393, a2 = 0.230389, a3 = 0.000972, a4 = 0.078108

(maximum error: 2.5×10−5)

where p = 0.47047, a1 = 0.3480242, a2 = −0.0958798, a3 = 0.7478556

(maximum error: 3×10−7)

where a1 = 0.0705230784, a2 = 0.0422820123, a3 = 0.0092705272, a4 = 0.0001520143, a5 = 0.0002765672, a6 = 0.0000430638

(maximum error: 1.5×10−7)

where p = 0.3275911, a1 = 0.254829592, a2 = −0.284496736, a3 = 1.421413741, a4 = −1.453152027, a5 = 1.061405429

All of these approximations are valid for x ≥ 0. To use these approximations for negative x, use the fact that erf x is an odd function, so erf x = −erf(−x).

- Exponential bounds and a pure exponential approximation for the complementary error function are given by[13]

- The above have been generalized to sums of N exponentials[14] with increasing accuracy in terms of N so that erfc x can be accurately approximated or bounded by 2Q̃(√2x), where

In particular, there is a systematic methodology to solve the numerical coefficients {(an,bn)}N

n = 1 that yield a minimax approximation or bound for the closely related Q-function: Q(x) ≈ Q̃(x), Q(x) ≤ Q̃(x), or Q(x) ≥ Q̃(x) for x ≥ 0. The coefficients {(an,bn)}N

n = 1 for many variations of the exponential approximations and bounds up to N = 25 have been released to open access as a comprehensive dataset.[15] - A tight approximation of the complementary error function for x ∈ [0,∞) is given by Karagiannidis & Lioumpas (2007)[16] who showed for the appropriate choice of parameters {A,B} that

They determined {A,B} = {1.98,1.135}, which gave a good approximation for all x ≥ 0. Alternative coefficients are also available for tailoring accuracy for a specific application or transforming the expression into a tight bound.[17]

- A single-term lower bound is[18]

where the parameter β can be picked to minimize error on the desired interval of approximation.

-

- Another approximation is given by Sergei Winitzki using his «global Padé approximations»:[19][20]: 2–3

where

This is designed to be very accurate in a neighborhood of 0 and a neighborhood of infinity, and the relative error is less than 0.00035 for all real x. Using the alternate value a ≈ 0.147 reduces the maximum relative error to about 0.00013.[21]

This approximation can be inverted to obtain an approximation for the inverse error function:

- An approximation with a maximal error of 1.2×10−7 for any real argument is:[22]

with

and

Table of values[edit]

| x | erf x | 1 − erf x |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0.02 | 0.022564575 | 0.977435425 |

| 0.04 | 0.045111106 | 0.954888894 |

| 0.06 | 0.067621594 | 0.932378406 |

| 0.08 | 0.090078126 | 0.909921874 |

| 0.1 | 0.112462916 | 0.887537084 |

| 0.2 | 0.222702589 | 0.777297411 |

| 0.3 | 0.328626759 | 0.671373241 |

| 0.4 | 0.428392355 | 0.571607645 |

| 0.5 | 0.520499878 | 0.479500122 |

| 0.6 | 0.603856091 | 0.396143909 |

| 0.7 | 0.677801194 | 0.322198806 |

| 0.8 | 0.742100965 | 0.257899035 |

| 0.9 | 0.796908212 | 0.203091788 |

| 1 | 0.842700793 | 0.157299207 |

| 1.1 | 0.880205070 | 0.119794930 |

| 1.2 | 0.910313978 | 0.089686022 |

| 1.3 | 0.934007945 | 0.065992055 |

| 1.4 | 0.952285120 | 0.047714880 |

| 1.5 | 0.966105146 | 0.033894854 |

| 1.6 | 0.976348383 | 0.023651617 |

| 1.7 | 0.983790459 | 0.016209541 |

| 1.8 | 0.989090502 | 0.010909498 |

| 1.9 | 0.992790429 | 0.007209571 |

| 2 | 0.995322265 | 0.004677735 |

| 2.1 | 0.997020533 | 0.002979467 |

| 2.2 | 0.998137154 | 0.001862846 |

| 2.3 | 0.998856823 | 0.001143177 |

| 2.4 | 0.999311486 | 0.000688514 |

| 2.5 | 0.999593048 | 0.000406952 |

| 3 | 0.999977910 | 0.000022090 |

| 3.5 | 0.999999257 | 0.000000743 |

[edit]

Complementary error function[edit]

The complementary error function, denoted erfc, is defined as

-

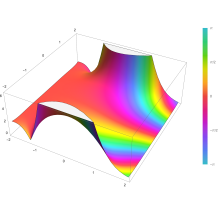

Plot of the complementary error function Erfc(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D

which also defines erfcx, the scaled complementary error function[23] (which can be used instead of erfc to avoid arithmetic underflow[23][24]). Another form of erfc x for x ≥ 0 is known as Craig’s formula, after its discoverer:[25]

This expression is valid only for positive values of x, but it can be used in conjunction with erfc x = 2 − erfc(−x) to obtain erfc(x) for negative values. This form is advantageous in that the range of integration is fixed and finite. An extension of this expression for the erfc of the sum of two non-negative variables is as follows:[26]

Imaginary error function[edit]

The imaginary error function, denoted erfi, is defined as

Plot of the imaginary error function Erfi(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D

where D(x) is the Dawson function (which can be used instead of erfi to avoid arithmetic overflow[23]).

Despite the name «imaginary error function», erfi x is real when x is real.

When the error function is evaluated for arbitrary complex arguments z, the resulting complex error function is usually discussed in scaled form as the Faddeeva function:

Cumulative distribution function[edit]

The error function is essentially identical to the standard normal cumulative distribution function, denoted Φ, also named norm(x) by some software languages[citation needed], as they differ only by scaling and translation. Indeed,

-

the normal cumulative distribution function plotted in the complex plane

or rearranged for erf and erfc:

Consequently, the error function is also closely related to the Q-function, which is the tail probability of the standard normal distribution. The Q-function can be expressed in terms of the error function as

The inverse of Φ is known as the normal quantile function, or probit function and may be expressed in terms of the inverse error function as

The standard normal cdf is used more often in probability and statistics, and the error function is used more often in other branches of mathematics.

The error function is a special case of the Mittag-Leffler function, and can also be expressed as a confluent hypergeometric function (Kummer’s function):

It has a simple expression in terms of the Fresnel integral.[further explanation needed]

In terms of the regularized gamma function P and the incomplete gamma function,

sgn x is the sign function.

Generalized error functions[edit]

Graph of generalised error functions En(x):

grey curve: E1(x) = 1 − e−x/√π

red curve: E2(x) = erf(x)

green curve: E3(x)

blue curve: E4(x)

gold curve: E5(x).

Some authors discuss the more general functions:[citation needed]

Notable cases are:

- E0(x) is a straight line through the origin: E0(x) = x/e√π

- E2(x) is the error function, erf x.

After division by n!, all the En for odd n look similar (but not identical) to each other. Similarly, the En for even n look similar (but not identical) to each other after a simple division by n!. All generalised error functions for n > 0 look similar on the positive x side of the graph.

These generalised functions can equivalently be expressed for x > 0 using the gamma function and incomplete gamma function:

Therefore, we can define the error function in terms of the incomplete gamma function:

Iterated integrals of the complementary error function[edit]

The iterated integrals of the complementary error function are defined by[27]

The general recurrence formula is

They have the power series

from which follow the symmetry properties

and

Implementations[edit]

As real function of a real argument[edit]

- In Posix-compliant operating systems, the header

math.hshall declare and the mathematical librarylibmshall provide the functionserfanderfc(double precision) as well as their single precision and extended precision counterpartserff,erflanderfcf,erfcl.[28] - The GNU Scientific Library provides

erf,erfc,log(erf), and scaled error functions.[29]

As complex function of a complex argument[edit]

libcerf, numeric C library for complex error functions, provides the complex functionscerf,cerfc,cerfcxand the real functionserfi,erfcxwith approximately 13–14 digits precision, based on the Faddeeva function as implemented in the MIT Faddeeva Package

See also[edit]

[edit]

- Gaussian integral, over the whole real line

- Gaussian function, derivative

- Dawson function, renormalized imaginary error function

- Goodwin–Staton integral

In probability[edit]

- Normal distribution

- Normal cumulative distribution function, a scaled and shifted form of error function

- Probit, the inverse or quantile function of the normal CDF

- Q-function, the tail probability of the normal distribution

References[edit]

- ^ Andrews, Larry C. (1998). Special functions of mathematics for engineers. SPIE Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780819426161.

- ^ Glaisher, James Whitbread Lee (July 1871). «On a class of definite integrals». London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 4. 42 (277): 294–302. doi:10.1080/14786447108640568. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ Glaisher, James Whitbread Lee (September 1871). «On a class of definite integrals. Part II». London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 4. 42 (279): 421–436. doi:10.1080/14786447108640600. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ «A007680 – OEIS». oeis.org. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Erf». MathWorld.

- ^ Schöpf, H. M.; Supancic, P. H. (2014). «On Bürmann’s Theorem and Its Application to Problems of Linear and Nonlinear Heat Transfer and Diffusion». The Mathematica Journal. 16. doi:10.3888/tmj.16-11.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Bürmann’s Theorem». MathWorld.

- ^ Bergsma, Wicher (2006). «On a new correlation coefficient, its orthogonal decomposition and associated tests of independence». arXiv:math/0604627.

- ^ Cuyt, Annie A. M.; Petersen, Vigdis B.; Verdonk, Brigitte; Waadeland, Haakon; Jones, William B. (2008). Handbook of Continued Fractions for Special Functions. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4020-6948-2.

- ^ Ng, Edward W.; Geller, Murray (January 1969). «A table of integrals of the Error functions». Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards Section B. 73B (1): 1. doi:10.6028/jres.073B.001.

- ^ Schlömilch, Oskar Xavier (1859). «Ueber facultätenreihen». Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik (in German). 4: 390–415. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Nielson, Niels (1906). Handbuch der Theorie der Gammafunktion (in German). Leipzig: B. G. Teubner. p. 283 Eq. 3. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Chiani, M.; Dardari, D.; Simon, M.K. (2003). «New Exponential Bounds and Approximations for the Computation of Error Probability in Fading Channels» (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications. 2 (4): 840–845. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.190.6761. doi:10.1109/TWC.2003.814350.

- ^ Tanash, I.M.; Riihonen, T. (2020). «Global minimax approximations and bounds for the Gaussian Q-function by sums of exponentials». IEEE Transactions on Communications. 68 (10): 6514–6524. arXiv:2007.06939. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2020.3006902. S2CID 220514754.

- ^ Tanash, I.M.; Riihonen, T. (2020). «Coefficients for Global Minimax Approximations and Bounds for the Gaussian Q-Function by Sums of Exponentials [Data set]». Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4112978.

- ^ Karagiannidis, G. K.; Lioumpas, A. S. (2007). «An improved approximation for the Gaussian Q-function» (PDF). IEEE Communications Letters. 11 (8): 644–646. doi:10.1109/LCOMM.2007.070470. S2CID 4043576.

- ^ Tanash, I.M.; Riihonen, T. (2021). «Improved coefficients for the Karagiannidis–Lioumpas approximations and bounds to the Gaussian Q-function». IEEE Communications Letters. 25 (5): 1468–1471. arXiv:2101.07631. doi:10.1109/LCOMM.2021.3052257. S2CID 231639206.

- ^ Chang, Seok-Ho; Cosman, Pamela C.; Milstein, Laurence B. (November 2011). «Chernoff-Type Bounds for the Gaussian Error Function». IEEE Transactions on Communications. 59 (11): 2939–2944. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2011.072011.100049. S2CID 13636638.

- ^ Winitzki, Sergei (2003). «Uniform approximations for transcendental functions». Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2003. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2667. Springer, Berlin. pp. 780–789. doi:10.1007/3-540-44839-X_82. ISBN 978-3-540-40155-1.

- ^ Zeng, Caibin; Chen, Yang Cuan (2015). «Global Padé approximations of the generalized Mittag-Leffler function and its inverse». Fractional Calculus and Applied Analysis. 18 (6): 1492–1506. arXiv:1310.5592. doi:10.1515/fca-2015-0086. S2CID 118148950.

Indeed, Winitzki [32] provided the so-called global Padé approximation

- ^ Winitzki, Sergei (6 February 2008). «A handy approximation for the error function and its inverse».

- ^ Numerical Recipes in Fortran 77: The Art of Scientific Computing (ISBN 0-521-43064-X), 1992, page 214, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Cody, W. J. (March 1993), «Algorithm 715: SPECFUN—A portable FORTRAN package of special function routines and test drivers» (PDF), ACM Trans. Math. Softw., 19 (1): 22–32, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.643.4394, doi:10.1145/151271.151273, S2CID 5621105

- ^ Zaghloul, M. R. (1 March 2007), «On the calculation of the Voigt line profile: a single proper integral with a damped sine integrand», Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 375 (3): 1043–1048, Bibcode:2007MNRAS.375.1043Z, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11377.x

- ^ John W. Craig, A new, simple and exact result for calculating the probability of error for two-dimensional signal constellations Archived 3 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Proceedings of the 1991 IEEE Military Communication Conference, vol. 2, pp. 571–575.

- ^ Behnad, Aydin (2020). «A Novel Extension to Craig’s Q-Function Formula and Its Application in Dual-Branch EGC Performance Analysis». IEEE Transactions on Communications. 68 (7): 4117–4125. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2020.2986209. S2CID 216500014.

- ^ Carslaw, H. S.; Jaeger, J. C. (1959), Conduction of Heat in Solids (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-853368-9, p 484

- ^ https://pubs.opengroup.org/onlinepubs/9699919799/basedefs/math.h.html

- ^ «Special Functions – GSL 2.7 documentation».

Further reading[edit]

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene Ann, eds. (1983) [June 1964]. «Chapter 7». Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Applied Mathematics Series. Vol. 55 (Ninth reprint with additional corrections of tenth original printing with corrections (December 1972); first ed.). Washington D.C.; New York: United States Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards; Dover Publications. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0. LCCN 64-60036. MR 0167642. LCCN 65-12253.

- Press, William H.; Teukolsky, Saul A.; Vetterling, William T.; Flannery, Brian P. (2007), «Section 6.2. Incomplete Gamma Function and Error Function», Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8

- Temme, Nico M. (2010), «Error Functions, Dawson’s and Fresnel Integrals», in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W. (eds.), NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5, MR 2723248

External links[edit]

- A Table of Integrals of the Error Functions

| Error function | |

|---|---|

Plot of the error function |

|

| General information | |

| General definition |  |

| Fields of application | Probability, thermodynamics |

| Domain, Codomain and Image | |

| Domain |  |

| Image |  |

| Basic features | |

| Parity | Odd |

| Specific features | |

| Root | 0 |

| Derivative |  |

| Antiderivative |  |

| Series definition | |

| Taylor series |  |

In mathematics, the error function (also called the Gauss error function), often denoted by erf, is a complex function of a complex variable defined as:[1]

This integral is a special (non-elementary) sigmoid function that occurs often in probability, statistics, and partial differential equations. In many of these applications, the function argument is a real number. If the function argument is real, then the function value is also real.

In statistics, for non-negative values of x, the error function has the following interpretation: for a random variable Y that is normally distributed with mean 0 and standard deviation 1/√2, erf x is the probability that Y falls in the range [−x, x].

Two closely related functions are the complementary error function (erfc) defined as

and the imaginary error function (erfi) defined as

where i is the imaginary unit

Name[edit]

The name «error function» and its abbreviation erf were proposed by J. W. L. Glaisher in 1871 on account of its connection with «the theory of Probability, and notably the theory of Errors.»[2] The error function complement was also discussed by Glaisher in a separate publication in the same year.[3]

For the «law of facility» of errors whose density is given by

(the normal distribution), Glaisher calculates the probability of an error lying between p and q as:

Plot of the error function Erf(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D

Applications[edit]

When the results of a series of measurements are described by a normal distribution with standard deviation σ and expected value 0, then erf (a/σ √2) is the probability that the error of a single measurement lies between −a and +a, for positive a. This is useful, for example, in determining the bit error rate of a digital communication system.

The error and complementary error functions occur, for example, in solutions of the heat equation when boundary conditions are given by the Heaviside step function.

The error function and its approximations can be used to estimate results that hold with high probability or with low probability. Given a random variable X ~ Norm[μ,σ] (a normal distribution with mean μ and standard deviation σ) and a constant L < μ:

where A and B are certain numeric constants. If L is sufficiently far from the mean, specifically μ − L ≥ σ√ln k, then:

so the probability goes to 0 as k → ∞.

The probability for X being in the interval [La, Lb] can be derived as

Properties[edit]

Integrand exp(−z2)

erf z

The property erf (−z) = −erf z means that the error function is an odd function. This directly results from the fact that the integrand e−t2 is an even function (the antiderivative of an even function which is zero at the origin is an odd function and vice versa).

Since the error function is an entire function which takes real numbers to real numbers, for any complex number z:

where z is the complex conjugate of z.

The integrand f = exp(−z2) and f = erf z are shown in the complex z-plane in the figures at right with domain coloring.

The error function at +∞ is exactly 1 (see Gaussian integral). At the real axis, erf z approaches unity at z → +∞ and −1 at z → −∞. At the imaginary axis, it tends to ±i∞.

Taylor series[edit]

The error function is an entire function; it has no singularities (except that at infinity) and its Taylor expansion always converges, but is famously known «[…] for its bad convergence if x > 1.»[4]

The defining integral cannot be evaluated in closed form in terms of elementary functions, but by expanding the integrand e−z2 into its Maclaurin series and integrating term by term, one obtains the error function’s Maclaurin series as:

which holds for every complex number z. The denominator terms are sequence A007680 in the OEIS.

For iterative calculation of the above series, the following alternative formulation may be useful:

because −(2k − 1)z2/k(2k + 1) expresses the multiplier to turn the kth term into the (k + 1)th term (considering z as the first term).

The imaginary error function has a very similar Maclaurin series, which is:

which holds for every complex number z.

Derivative and integral[edit]

The derivative of the error function follows immediately from its definition:

From this, the derivative of the imaginary error function is also immediate:

An antiderivative of the error function, obtainable by integration by parts, is

An antiderivative of the imaginary error function, also obtainable by integration by parts, is

Higher order derivatives are given by

where H are the physicists’ Hermite polynomials.[5]

Bürmann series[edit]

An expansion,[6] which converges more rapidly for all real values of x than a Taylor expansion, is obtained by using Hans Heinrich Bürmann’s theorem:[7]

where sgn is the sign function. By keeping only the first two coefficients and choosing c1 = 31/200 and c2 = −341/8000, the resulting approximation shows its largest relative error at x = ±1.3796, where it is less than 0.0036127:

Inverse functions[edit]

Given a complex number z, there is not a unique complex number w satisfying erf w = z, so a true inverse function would be multivalued. However, for −1 < x < 1, there is a unique real number denoted erf−1 x satisfying

The inverse error function is usually defined with domain (−1,1), and it is restricted to this domain in many computer algebra systems. However, it can be extended to the disk |z| < 1 of the complex plane, using the Maclaurin series

where c0 = 1 and

So we have the series expansion (common factors have been canceled from numerators and denominators):

(After cancellation the numerator/denominator fractions are entries OEIS: A092676/OEIS: A092677 in the OEIS; without cancellation the numerator terms are given in entry OEIS: A002067.) The error function’s value at ±∞ is equal to ±1.

For |z| < 1, we have erf(erf−1 z) = z.

The inverse complementary error function is defined as

For real x, there is a unique real number erfi−1 x satisfying erfi(erfi−1 x) = x. The inverse imaginary error function is defined as erfi−1 x.[8]

For any real x, Newton’s method can be used to compute erfi−1 x, and for −1 ≤ x ≤ 1, the following Maclaurin series converges:

where ck is defined as above.

Asymptotic expansion[edit]

A useful asymptotic expansion of the complementary error function (and therefore also of the error function) for large real x is

where (2n − 1)!! is the double factorial of (2n − 1), which is the product of all odd numbers up to (2n − 1). This series diverges for every finite x, and its meaning as asymptotic expansion is that for any integer N ≥ 1 one has

where the remainder, in Landau notation, is

as x → ∞.

Indeed, the exact value of the remainder is

which follows easily by induction, writing

and integrating by parts.

For large enough values of x, only the first few terms of this asymptotic expansion are needed to obtain a good approximation of erfc x (while for not too large values of x, the above Taylor expansion at 0 provides a very fast convergence).

Continued fraction expansion[edit]

A continued fraction expansion of the complementary error function is:[9]

Integral of error function with Gaussian density function[edit]

which appears related to Ng and Geller, formula 13 in section 4.3[10] with a change of variables.

Factorial series[edit]

The inverse factorial series:

converges for Re(z2) > 0. Here

zn denotes the rising factorial, and s(n,k) denotes a signed Stirling number of the first kind.[11][12]

There also exists a representation by an infinite sum containing the double factorial:

Numerical approximations[edit]

Approximation with elementary functions[edit]

- Abramowitz and Stegun give several approximations of varying accuracy (equations 7.1.25–28). This allows one to choose the fastest approximation suitable for a given application. In order of increasing accuracy, they are:

(maximum error: 5×10−4)

where a1 = 0.278393, a2 = 0.230389, a3 = 0.000972, a4 = 0.078108

(maximum error: 2.5×10−5)

where p = 0.47047, a1 = 0.3480242, a2 = −0.0958798, a3 = 0.7478556

(maximum error: 3×10−7)

where a1 = 0.0705230784, a2 = 0.0422820123, a3 = 0.0092705272, a4 = 0.0001520143, a5 = 0.0002765672, a6 = 0.0000430638

(maximum error: 1.5×10−7)

where p = 0.3275911, a1 = 0.254829592, a2 = −0.284496736, a3 = 1.421413741, a4 = −1.453152027, a5 = 1.061405429

All of these approximations are valid for x ≥ 0. To use these approximations for negative x, use the fact that erf x is an odd function, so erf x = −erf(−x).

- Exponential bounds and a pure exponential approximation for the complementary error function are given by[13]

- The above have been generalized to sums of N exponentials[14] with increasing accuracy in terms of N so that erfc x can be accurately approximated or bounded by 2Q̃(√2x), where

In particular, there is a systematic methodology to solve the numerical coefficients {(an,bn)}N

n = 1 that yield a minimax approximation or bound for the closely related Q-function: Q(x) ≈ Q̃(x), Q(x) ≤ Q̃(x), or Q(x) ≥ Q̃(x) for x ≥ 0. The coefficients {(an,bn)}N

n = 1 for many variations of the exponential approximations and bounds up to N = 25 have been released to open access as a comprehensive dataset.[15] - A tight approximation of the complementary error function for x ∈ [0,∞) is given by Karagiannidis & Lioumpas (2007)[16] who showed for the appropriate choice of parameters {A,B} that

They determined {A,B} = {1.98,1.135}, which gave a good approximation for all x ≥ 0. Alternative coefficients are also available for tailoring accuracy for a specific application or transforming the expression into a tight bound.[17]

- A single-term lower bound is[18]

where the parameter β can be picked to minimize error on the desired interval of approximation.

-

- Another approximation is given by Sergei Winitzki using his «global Padé approximations»:[19][20]: 2–3

where

This is designed to be very accurate in a neighborhood of 0 and a neighborhood of infinity, and the relative error is less than 0.00035 for all real x. Using the alternate value a ≈ 0.147 reduces the maximum relative error to about 0.00013.[21]

This approximation can be inverted to obtain an approximation for the inverse error function:

- An approximation with a maximal error of 1.2×10−7 for any real argument is:[22]

with

and

Table of values[edit]

| x | erf x | 1 − erf x |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 0.02 | 0.022564575 | 0.977435425 |

| 0.04 | 0.045111106 | 0.954888894 |

| 0.06 | 0.067621594 | 0.932378406 |

| 0.08 | 0.090078126 | 0.909921874 |

| 0.1 | 0.112462916 | 0.887537084 |

| 0.2 | 0.222702589 | 0.777297411 |

| 0.3 | 0.328626759 | 0.671373241 |

| 0.4 | 0.428392355 | 0.571607645 |

| 0.5 | 0.520499878 | 0.479500122 |

| 0.6 | 0.603856091 | 0.396143909 |

| 0.7 | 0.677801194 | 0.322198806 |

| 0.8 | 0.742100965 | 0.257899035 |

| 0.9 | 0.796908212 | 0.203091788 |

| 1 | 0.842700793 | 0.157299207 |

| 1.1 | 0.880205070 | 0.119794930 |

| 1.2 | 0.910313978 | 0.089686022 |

| 1.3 | 0.934007945 | 0.065992055 |

| 1.4 | 0.952285120 | 0.047714880 |

| 1.5 | 0.966105146 | 0.033894854 |

| 1.6 | 0.976348383 | 0.023651617 |

| 1.7 | 0.983790459 | 0.016209541 |

| 1.8 | 0.989090502 | 0.010909498 |

| 1.9 | 0.992790429 | 0.007209571 |

| 2 | 0.995322265 | 0.004677735 |

| 2.1 | 0.997020533 | 0.002979467 |

| 2.2 | 0.998137154 | 0.001862846 |

| 2.3 | 0.998856823 | 0.001143177 |

| 2.4 | 0.999311486 | 0.000688514 |

| 2.5 | 0.999593048 | 0.000406952 |

| 3 | 0.999977910 | 0.000022090 |

| 3.5 | 0.999999257 | 0.000000743 |

[edit]

Complementary error function[edit]

The complementary error function, denoted erfc, is defined as

-

Plot of the complementary error function Erfc(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D

which also defines erfcx, the scaled complementary error function[23] (which can be used instead of erfc to avoid arithmetic underflow[23][24]). Another form of erfc x for x ≥ 0 is known as Craig’s formula, after its discoverer:[25]

This expression is valid only for positive values of x, but it can be used in conjunction with erfc x = 2 − erfc(−x) to obtain erfc(x) for negative values. This form is advantageous in that the range of integration is fixed and finite. An extension of this expression for the erfc of the sum of two non-negative variables is as follows:[26]

Imaginary error function[edit]

The imaginary error function, denoted erfi, is defined as

Plot of the imaginary error function Erfi(z) in the complex plane from -2-2i to 2+2i with colors created with Mathematica 13.1 function ComplexPlot3D

where D(x) is the Dawson function (which can be used instead of erfi to avoid arithmetic overflow[23]).

Despite the name «imaginary error function», erfi x is real when x is real.

When the error function is evaluated for arbitrary complex arguments z, the resulting complex error function is usually discussed in scaled form as the Faddeeva function:

Cumulative distribution function[edit]

The error function is essentially identical to the standard normal cumulative distribution function, denoted Φ, also named norm(x) by some software languages[citation needed], as they differ only by scaling and translation. Indeed,

-

the normal cumulative distribution function plotted in the complex plane

or rearranged for erf and erfc:

Consequently, the error function is also closely related to the Q-function, which is the tail probability of the standard normal distribution. The Q-function can be expressed in terms of the error function as

The inverse of Φ is known as the normal quantile function, or probit function and may be expressed in terms of the inverse error function as

The standard normal cdf is used more often in probability and statistics, and the error function is used more often in other branches of mathematics.

The error function is a special case of the Mittag-Leffler function, and can also be expressed as a confluent hypergeometric function (Kummer’s function):

It has a simple expression in terms of the Fresnel integral.[further explanation needed]

In terms of the regularized gamma function P and the incomplete gamma function,

sgn x is the sign function.

Generalized error functions[edit]

Graph of generalised error functions En(x):

grey curve: E1(x) = 1 − e−x/√π

red curve: E2(x) = erf(x)

green curve: E3(x)

blue curve: E4(x)

gold curve: E5(x).

Some authors discuss the more general functions:[citation needed]

Notable cases are:

- E0(x) is a straight line through the origin: E0(x) = x/e√π

- E2(x) is the error function, erf x.

After division by n!, all the En for odd n look similar (but not identical) to each other. Similarly, the En for even n look similar (but not identical) to each other after a simple division by n!. All generalised error functions for n > 0 look similar on the positive x side of the graph.

These generalised functions can equivalently be expressed for x > 0 using the gamma function and incomplete gamma function:

Therefore, we can define the error function in terms of the incomplete gamma function:

Iterated integrals of the complementary error function[edit]

The iterated integrals of the complementary error function are defined by[27]

The general recurrence formula is

They have the power series

from which follow the symmetry properties

and

Implementations[edit]

As real function of a real argument[edit]

- In Posix-compliant operating systems, the header

math.hshall declare and the mathematical librarylibmshall provide the functionserfanderfc(double precision) as well as their single precision and extended precision counterpartserff,erflanderfcf,erfcl.[28] - The GNU Scientific Library provides

erf,erfc,log(erf), and scaled error functions.[29]

As complex function of a complex argument[edit]

libcerf, numeric C library for complex error functions, provides the complex functionscerf,cerfc,cerfcxand the real functionserfi,erfcxwith approximately 13–14 digits precision, based on the Faddeeva function as implemented in the MIT Faddeeva Package

See also[edit]

[edit]

- Gaussian integral, over the whole real line

- Gaussian function, derivative

- Dawson function, renormalized imaginary error function

- Goodwin–Staton integral

In probability[edit]

- Normal distribution

- Normal cumulative distribution function, a scaled and shifted form of error function

- Probit, the inverse or quantile function of the normal CDF

- Q-function, the tail probability of the normal distribution

References[edit]

- ^ Andrews, Larry C. (1998). Special functions of mathematics for engineers. SPIE Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780819426161.

- ^ Glaisher, James Whitbread Lee (July 1871). «On a class of definite integrals». London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 4. 42 (277): 294–302. doi:10.1080/14786447108640568. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ Glaisher, James Whitbread Lee (September 1871). «On a class of definite integrals. Part II». London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science. 4. 42 (279): 421–436. doi:10.1080/14786447108640600. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ «A007680 – OEIS». oeis.org. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Erf». MathWorld.

- ^ Schöpf, H. M.; Supancic, P. H. (2014). «On Bürmann’s Theorem and Its Application to Problems of Linear and Nonlinear Heat Transfer and Diffusion». The Mathematica Journal. 16. doi:10.3888/tmj.16-11.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. «Bürmann’s Theorem». MathWorld.

- ^ Bergsma, Wicher (2006). «On a new correlation coefficient, its orthogonal decomposition and associated tests of independence». arXiv:math/0604627.

- ^ Cuyt, Annie A. M.; Petersen, Vigdis B.; Verdonk, Brigitte; Waadeland, Haakon; Jones, William B. (2008). Handbook of Continued Fractions for Special Functions. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4020-6948-2.

- ^ Ng, Edward W.; Geller, Murray (January 1969). «A table of integrals of the Error functions». Journal of Research of the National Bureau of Standards Section B. 73B (1): 1. doi:10.6028/jres.073B.001.

- ^ Schlömilch, Oskar Xavier (1859). «Ueber facultätenreihen». Zeitschrift für Mathematik und Physik (in German). 4: 390–415. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Nielson, Niels (1906). Handbuch der Theorie der Gammafunktion (in German). Leipzig: B. G. Teubner. p. 283 Eq. 3. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Chiani, M.; Dardari, D.; Simon, M.K. (2003). «New Exponential Bounds and Approximations for the Computation of Error Probability in Fading Channels» (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications. 2 (4): 840–845. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.190.6761. doi:10.1109/TWC.2003.814350.

- ^ Tanash, I.M.; Riihonen, T. (2020). «Global minimax approximations and bounds for the Gaussian Q-function by sums of exponentials». IEEE Transactions on Communications. 68 (10): 6514–6524. arXiv:2007.06939. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2020.3006902. S2CID 220514754.

- ^ Tanash, I.M.; Riihonen, T. (2020). «Coefficients for Global Minimax Approximations and Bounds for the Gaussian Q-Function by Sums of Exponentials [Data set]». Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.4112978.

- ^ Karagiannidis, G. K.; Lioumpas, A. S. (2007). «An improved approximation for the Gaussian Q-function» (PDF). IEEE Communications Letters. 11 (8): 644–646. doi:10.1109/LCOMM.2007.070470. S2CID 4043576.

- ^ Tanash, I.M.; Riihonen, T. (2021). «Improved coefficients for the Karagiannidis–Lioumpas approximations and bounds to the Gaussian Q-function». IEEE Communications Letters. 25 (5): 1468–1471. arXiv:2101.07631. doi:10.1109/LCOMM.2021.3052257. S2CID 231639206.

- ^ Chang, Seok-Ho; Cosman, Pamela C.; Milstein, Laurence B. (November 2011). «Chernoff-Type Bounds for the Gaussian Error Function». IEEE Transactions on Communications. 59 (11): 2939–2944. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2011.072011.100049. S2CID 13636638.

- ^ Winitzki, Sergei (2003). «Uniform approximations for transcendental functions». Computational Science and Its Applications – ICCSA 2003. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 2667. Springer, Berlin. pp. 780–789. doi:10.1007/3-540-44839-X_82. ISBN 978-3-540-40155-1.

- ^ Zeng, Caibin; Chen, Yang Cuan (2015). «Global Padé approximations of the generalized Mittag-Leffler function and its inverse». Fractional Calculus and Applied Analysis. 18 (6): 1492–1506. arXiv:1310.5592. doi:10.1515/fca-2015-0086. S2CID 118148950.

Indeed, Winitzki [32] provided the so-called global Padé approximation

- ^ Winitzki, Sergei (6 February 2008). «A handy approximation for the error function and its inverse».

- ^ Numerical Recipes in Fortran 77: The Art of Scientific Computing (ISBN 0-521-43064-X), 1992, page 214, Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Cody, W. J. (March 1993), «Algorithm 715: SPECFUN—A portable FORTRAN package of special function routines and test drivers» (PDF), ACM Trans. Math. Softw., 19 (1): 22–32, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.643.4394, doi:10.1145/151271.151273, S2CID 5621105

- ^ Zaghloul, M. R. (1 March 2007), «On the calculation of the Voigt line profile: a single proper integral with a damped sine integrand», Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, 375 (3): 1043–1048, Bibcode:2007MNRAS.375.1043Z, doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.11377.x

- ^ John W. Craig, A new, simple and exact result for calculating the probability of error for two-dimensional signal constellations Archived 3 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Proceedings of the 1991 IEEE Military Communication Conference, vol. 2, pp. 571–575.

- ^ Behnad, Aydin (2020). «A Novel Extension to Craig’s Q-Function Formula and Its Application in Dual-Branch EGC Performance Analysis». IEEE Transactions on Communications. 68 (7): 4117–4125. doi:10.1109/TCOMM.2020.2986209. S2CID 216500014.

- ^ Carslaw, H. S.; Jaeger, J. C. (1959), Conduction of Heat in Solids (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-853368-9, p 484

- ^ https://pubs.opengroup.org/onlinepubs/9699919799/basedefs/math.h.html

- ^ «Special Functions – GSL 2.7 documentation».

Further reading[edit]

- Abramowitz, Milton; Stegun, Irene Ann, eds. (1983) [June 1964]. «Chapter 7». Handbook of Mathematical Functions with Formulas, Graphs, and Mathematical Tables. Applied Mathematics Series. Vol. 55 (Ninth reprint with additional corrections of tenth original printing with corrections (December 1972); first ed.). Washington D.C.; New York: United States Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards; Dover Publications. p. 297. ISBN 978-0-486-61272-0. LCCN 64-60036. MR 0167642. LCCN 65-12253.

- Press, William H.; Teukolsky, Saul A.; Vetterling, William T.; Flannery, Brian P. (2007), «Section 6.2. Incomplete Gamma Function and Error Function», Numerical Recipes: The Art of Scientific Computing (3rd ed.), New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8

- Temme, Nico M. (2010), «Error Functions, Dawson’s and Fresnel Integrals», in Olver, Frank W. J.; Lozier, Daniel M.; Boisvert, Ronald F.; Clark, Charles W. (eds.), NIST Handbook of Mathematical Functions, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-19225-5, MR 2723248

External links[edit]

- A Table of Integrals of the Error Functions

Дополнительная функция ошибок

Синтаксис

Описание

Примеры

Дополнительная функция ошибок для с плавающей точкой и символьных чисел

В зависимости от его аргументов, erfc может возвратить или точные символьные результаты с плавающей точкой.

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для этих чисел. Поскольку эти числа не являются символьными объектами, вы получаете результаты с плавающей точкой:

A = [erfc(1/2), erfc(1.41), erfc(sqrt(2))]

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для тех же чисел, преобразованных в символьные объекты. Для большинства символьных (точных) чисел, erfc отвечает на неразрешенные символьные звонки:

symA = [erfc(sym(1/2)), erfc(sym(1.41)), erfc(sqrt(sym(2)))]

symA = [ erfc(1/2), erfc(141/100), erfc(2^(1/2))]

Использование vpa аппроксимировать символьные результаты необходимым количеством цифр:

d = digits(10); vpa(symA) digits(d)

ans = [ 0.4795001222, 0.04614756064, 0.0455002639]

Функция ошибок для переменных и выражений

Для большинства символьных переменных и выражений, erfc отвечает на неразрешенные символьные звонки.

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для x и sin(x) + x*exp(x):

syms x f = sin(x) + x*exp(x); erfc(x) erfc(f)

ans = erfc(x) ans = erfc(sin(x) + x*exp(x))

Дополнительная функция ошибок для векторов и матриц

Если входной параметр является вектором или матрицей, erfc возвращает дополнительную функцию ошибок для каждого элемента того вектора или матрицы.

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для элементов матричного M и векторный V:

M = sym([0 inf; 1/3 -inf]); V = sym([1; -i*inf]); erfc(M) erfc(V)

ans =

[ 1, 0]

[ erfc(1/3), 2]

ans =

erfc(1)

1 + Inf*1i

Вычислите повторный интеграл дополнительной функции ошибок для элементов V и M, и целочисленный -1:

ans =

[ 2/pi^(1/2), 0]

[ (2*exp(-1/9))/pi^(1/2), 0]

ans =

(2*exp(-1))/pi^(1/2)

Inf

Специальные значения дополнительной функции ошибок

erfc возвращает специальные значения для конкретных параметров.

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для x = 0, x = ∞, и x = – ∞. Дополнительная функция ошибок имеет специальные значения для этих параметров:

[erfc(0), erfc(Inf), erfc(-Inf)]

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для комплексных бесконечностей. Использование sym преобразовывать комплексные бесконечности в символьные объекты:

[erfc(sym(i*Inf)), erfc(sym(-i*Inf))]

ans = [ 1 - Inf*1i, 1 + Inf*1i]

Обработка выражений, которые содержат дополнительную функцию ошибок

Много функций, такой как diff и int, может обработать выражения, содержащие erfc.

Вычислите первые и вторые производные дополнительной функции ошибок:

syms x diff(erfc(x), x) diff(erfc(x), x, 2)

ans = -(2*exp(-x^2))/pi^(1/2) ans = (4*x*exp(-x^2))/pi^(1/2)

Вычислите интегралы этих выражений:

syms x int(erfc(-1, x), x)

ans = x*erfc(x) - exp(-x^2)/pi^(1/2)

ans = (x^3*erfc(x))/6 - exp(-x^2)/(6*pi^(1/2)) +... (x*erfc(x))/4 - (x^2*exp(-x^2))/(6*pi^(1/2))

Постройте дополнительную функцию ошибок

Постройте дополнительную функцию ошибок на интервале от-5 до 5.

syms x fplot(erfc(x),[-5 5]) grid on

Входные параметры

свернуть все

X входной параметр

символьное число | символьная переменная | символьное выражение | символьная функция | символьный вектор | символьная матрица

Введите в виде символьного числа, переменной, выражения или функции, или как вектор или матрица символьных чисел, переменных, выражений или функций.

K — Введите представление целого числа, больше, чем -2

номер | символьное число | символьная переменная | символьное выражение | символьная функция | символьный вектор | символьная матрица

Введите представление целого числа, больше, чем -2В виде номера, символьного числа, переменной, выражения или функции. Это аргументы может также быть вектором или матрицей чисел, символьных чисел, переменных, выражений или функций.

Больше о

свернуть все

Дополнительная функция ошибок

Следующий интеграл задает дополнительную функцию ошибок:

Здесь erf(x) функция ошибок.

Повторный интеграл дополнительной функции ошибок

Следующий интеграл является повторным интегралом дополнительной функции ошибок:

Здесь, erfc(0,x)=erfc(x).

Советы

-

Вызов

erfcдля номера, который не является символьным объектом, вызывает MATLAB®erfcфункция. Эта функция принимает действительные аргументы только. Если вы хотите вычислить дополнительную функцию ошибок для комплексного числа, используйтеsymпреобразовывать тот номер в символьный объект, и затем вызыватьerfcдля того символьного объекта. -

Для большинства символьных (точных) чисел,

erfcотвечает на неразрешенные символьные звонки. Можно аппроксимировать такие результаты использованием чисел с плавающей запятойvpa. -

По крайней мере один входной параметр должен быть скаляром, или оба аргумента должны быть векторами или матрицами, одного размера. Если один входной параметр является скаляром, и другой является вектором или матрицей, то

erfcрасширяет скаляр в вектор или матрицу одного размера с другим аргументом со всеми элементами, равными тому скаляру.

Алгоритмы

Тулбокс может упростить выражения, которые содержат функции ошибок и их инверсии. Для действительных значений x, тулбокс применяет эти правила упрощения:

-

erfinv(erf(x)) = erfinv(1 - erfc(x)) = erfcinv(1 - erf(x)) = erfcinv(erfc(x)) = x -

erfinv(-erf(x)) = erfinv(erfc(x) - 1) = erfcinv(1 + erf(x)) = erfcinv(2 - erfc(x)) = -x

Для любого значения x, система применяет эти правила упрощения:

-

erfcinv(x) = erfinv(1 - x) -

erfinv(-x) = -erfinv(x) -

erfcinv(2 - x) = -erfcinv(x) -

erf(erfinv(x)) = erfc(erfcinv(x)) = x -

erf(erfcinv(x)) = erfc(erfinv(x)) = 1 - x

Ссылки

[1] Gautschi, W. “Функция ошибок и Интегралы Френели”. Руководство Математических функций с Формулами, Графиками и Математическими Таблицами. (М. Абрамовиц и я. А. Стегун, редакторы). Нью-Йорк: Дувр, 1972.

Представленный в R2011b

Excel for Microsoft 365 Excel for Microsoft 365 for Mac Excel for the web Excel 2021 Excel 2021 for Mac Excel 2019 Excel 2019 for Mac Excel 2016 Excel 2016 for Mac Excel 2013 Excel 2010 Excel 2007 Excel for Mac 2011 Excel Starter 2010 More…Less

This article describes the formula syntax and usage of the ERFC function in Microsoft Excel.

Description

Returns the complementary ERF function integrated between x and infinity.

Syntax

ERFC(x)

The ERFC function syntax has the following arguments:

-

X Required. The lower bound for integrating ERFC.

Remarks

-

If x is nonnumeric, ERFC returns the #VALUE! error value.

Example

Copy the example data in the following table, and paste it in cell A1 of a new Excel worksheet. For formulas to show results, select them, press F2, and then press Enter. If you need to, you can adjust the column widths to see all the data.

|

Formula |

Description |

Result |

|

=ERFC(1) |

Complementary ERF function of 1. |

0.15729921 |

Need more help?

Содержание

- 1. Функция math.erf(x). Функция ошибок

- 2. Функция math.erfc(x). Дополнительная функция ошибок

- 3. Функция math.gamma(x). Гамма-функция

- 4. Функция math.lgamma(x). Натуральный логарифм от гамма-функции

- 5. Константа math.pi. Число π

- 6. Константа math.e. Экспонента

- 7. Константа math.tau. Число 2·π

- 8. Константа math.inf. Положительная бесконечность

- 9. Константа math.nan. Значение NaN (not a number)

- Связанные темы

Поиск на других ресурсах:

1. Функция math.erf(x). Функция ошибок

Функция math.erf(x) в языке Python предназначена для вычисления функции ошибок от аргумента x. Функция ошибок еще называется функцией ошибок Гаусса и определяется по формуле

Более подробно об особенностях использования функции ошибок можно узнать из других источников.

Пример.

# Функция math.erf(x) import math x = 1.5 y = math.erf(x) # y = 0.9661051464753108 x = 0 y = math.erf(x) # y = 0.0

⇑

2. Функция math.erfc(x). Дополнительная функция ошибок

Функция math.erfc(x) используется для вычисления дополнительной функции ошибки в точке x. Дополнительная функция ошибки определяется как

1.0 - math.erf(x)

Функция math.erfc(x) используется в случаях, если значения x есть большими. При больших значениях x может произойти потеря значимости. Во избежание этого используется данная функция.

Функция math.erfc(x) используется в Python начиная с версии 3.2.

Пример.

# Функция math.erfc(x) import math x = 1.5 y = math.erfc(x) # y = 0.033894853524689274 x = 0 y = math.erfc(x) # y = 1.0

⇑

3. Функция math.gamma(x). Гамма функция

Функция math.gamma(x) возвращает Гамма-функцию от аргумента x. Гамма-функция вычисляется по формуле:

Более подробную информацию об использовании Гамма-функции можно найти в других источниках.

Функция math.gamma(x) введена в Python начиная с версии 3.2.

Пример.

# Функция math.gamma(x) import math x = 1.0 y = math.gamma(x) # y = 1.0 x = -2.2 y = math.gamma(x) # y = -2.2049805184191333 x = 3.8 y = math.gamma(x) # y = 4.694174205740421

⇑

4. Функция math.lgamma(x). Натуральный логарифм от гамма-функции

Функция math.lgamma(x) возвращает натуральный логарифм абсолютного значения Гамма-функции от аргумента x. Данная функция введена в Python начиная с версии 3.2.

Пример.

# Функция math.lgamma(x) import math x = 1.0 y = math.lgamma(x) # y = 0.0 x = 2.7 y = math.lgamma(x) # y = 0.4348205536551042

⇑

5. Константа math.pi. Число π

Константа math.pi определяет число π с доступной точностью.

Пример.

# Константа math.pi import math y = math.pi # y = 3.141592653589793 # Вычисление площади круга r = 2.0 s = math.pi*r*r # s = 12.566370614359172

⇑

6. Константа math.e. Экспонента

Константа math.e определяет значение экспоненты с доступной точностью.

Пример.

# Константа math.e - экспонента import math y = math.e # y = 2.718281828459045 x = 1.5 y = math.e**x # y = 4.4816890703380645

⇑

7. Константа math.tau. Число 2·π

Константа math.tau определяет число 2·π с доступной точностью. Значение math.tau равно отношению длины окружности к ее радиусу. Константа используется в Python начиная с версии 3.6.

Пример.

# Константа math.tau import math y = math.tau # y = 6.283185307179586 # Вычисление длины окружности радиуса r = 2 r = 2.0 length = math.tau*r # length = 12.566370614359172

⇑

8. Константа math.inf. Положительная бесконечность

Константа math.inf определяет положительную бесконеченость с плавающей запятой. Чтобы определить отрицательную бесконечность, нужно использовать –math.inf.

Константа math.inf равна значению

float('inf')

Константа введена в Python начиная с версии 3.5.

Пример.

# Константа math.inf import math y = math.inf # y = inf - положительная бесконечность print('y = ', y) y = float('inf') # y = inf print('y = ', y)

После запуска программы будет получен следующий результат

y = inf y = inf

⇑

9. Константа math.nan. Значение NaN (not a number)

Константа math.nan введена в Python версии 3.6 и равна значению NaN с плавающей запятой. Значение NaN может возникать в случаях, когда результат вычисления неопределен. Примером такого вычисления может быть деление ноль на ноль, умножение ноль на бесконечность.

Определить, принимает ли результат значение NaN можно также с помощью функции math.isnan(x).

Константа math.nan введена в Python начиная с версии 3.5. Значение константы эквивалентно значению

float('nan')

Пример.

# Константа math.nan import math y = math.nan # y = nan print('y = ', y) y = float('nan') # y = nan print('y = ', y)

Результат выполнения программы:

y = nan y = nan

⇑

Связанные темы

- Теоретико-числовые функции и функции представления

- Степенные и логарифмические функции

- Тригонометрические функции

- Гиперболические функции

⇑

Функция ERFC возвращает дополнительную функцию ошибки, интегрированную между нижним пределом и бесконечностью.

Синтаксис

=ERFC (x)

аргументы

- X (обязательно): нижний предел интеграции ERFC.

Возвращаемое значение

Функция ERFC возвращает числовое значение.

Примечания к функциям

- Функция ERFC была улучшена в Excel 2010 и теперь может вычислять отрицательные значения.

В Excel 2007 функция ERFC принимает только положительные значения. Если предоставленный аргумент является отрицательным значением, функция ERFC вернет #ЧИСЛО! значение ошибки. - Значение! значение ошибки возникает, если предоставленный аргумент x не является числовым.

- Значение! значение ошибки возникает, если предоставленный аргумент x не является числовым.

- Функция ERFC всегда возвращает положительный результат в диапазоне от 0 до 2, независимо от того, является ли предоставленный аргумент положительным или отрицательным.

- Уравнение дополнительной функции ошибок:

Примеры

Чтобы вычислить дополнительную функцию ошибки, интегрированную между нижним пределом, указанным в таблице ниже, и бесконечным значением, выполните следующие действия.

1. Пожалуйста, скопируйте приведенную ниже формулу в ячейку D6, затем нажмите клавишу Enter, чтобы получить результат.

=ERFC (B6)

2. Выберите эту ячейку результатов и перетащите ее маркер автозаполнения вниз, чтобы получить остальные результаты.

Заметки:

- Когда единственный аргумент x равен нулю (0), ERFC возвращает в качестве результата 1.

- Аргумент в каждой из приведенных выше формул предоставляется в виде ссылки на ячейку, содержащей числовое значение.

- Мы также можем напрямую ввести значение в формулу. Например, формулу в ячейке D6 можно изменить на:

=ERFC (-1)

Относительные функции:

-

Excel EVEN Функция

Функция EVEN округляет числа от нуля до ближайшего четного целого числа.

-

Excel EXP Функция

Функция EXP возвращает результат возведения константы e в энную степень.

Лучшие инструменты для работы в офисе

Kutools for Excel — поможет вам выделиться из толпы

Хотите быстро и качественно выполнять свою повседневную работу? Kutools for Excel предлагает мощные расширенные функции 300 (объединение книг, суммирование по цвету, разделение содержимого ячеек, преобразование даты и т. д.) и экономит для вас 80% времени.

- Разработан для 1500 рабочих сценариев, помогает решить 80% проблем с Excel.

- Уменьшите количество нажатий на клавиатуру и мышь каждый день, избавьтесь от усталости глаз и рук.

- Станьте экспертом по Excel за 3 минуты. Больше не нужно запоминать какие-либо болезненные формулы и коды VBA.

- 30-дневная неограниченная бесплатная пробная версия. 60-дневная гарантия возврата денег. Бесплатное обновление и поддержка 2 года.

Вкладка Office — включение чтения и редактирования с вкладками в Microsoft Office (включая Excel)

- Одна секунда для переключения между десятками открытых документов!

- Уменьшите количество щелчков мышью на сотни каждый день, попрощайтесь с рукой мыши.

- Повышает вашу продуктивность на 50% при просмотре и редактировании нескольких документов.

- Добавляет эффективные вкладки в Office (включая Excel), точно так же, как Chrome, Firefox и новый Internet Explorer.

Комментарии (0)

Оценок пока нет. Оцените первым!

Оставляйте свои комментарии

Время чтения 3 мин.

Метод Python math.erf() вернет ошибку в точке x. Функция ошибки также известна как функция ошибки Гаусса: она выдает ошибку, если в качестве параметра передается любое не числовое значение.

Python math.erfc() — это встроенный метод, определенный в математическом модуле, который используется для поиска дополнительной функции ошибок в точке x, если x — переданный параметр. Например, если x передается в качестве параметра в функцию erf(erf(x)), она возвращает дополнительную функцию ошибки.

Содержание

- Что такое функция erf() в Python?

- Синтаксис

- Параметры

- Возвращаемое значение

- Примеры программ по методу erf() в Python

- Пример 1. Программа, демонстрирующая работу метода erf()

- Пример 2. Программа для передачи значения вне допустимого диапазона из функции и отображения вывода

- Что такое функция erfc() в Python?

- Синтаксис

- Параметры

- Возвращаемое значение

- Примеры программ

- Пример 1. Программа, показывающая работу метода erfc()

- Пример 2. Передача значения вне допустимого диапазона из функции и отображения вывода

Python erf() — это встроенный метод, определенный в математическом модуле, который используется для поиска функции ошибки в точке x, если x является переданным параметром. Например, если x передается в качестве параметра в функцию erf(erf(x)), она возвращает функцию ошибки. Мы можем использовать математический модуль, импортировав его.

Синтаксис

Здесь var — это переменная, функцию ошибки которой мы должны найти.

Параметры

Имеет один аргумент var, который принимает значения числового типа данных и выдает TypeError, если передается аргумент любого другого типа данных.

Возвращаемое значение

Возвращает значение функции ошибки числа в типе данных float.

См. следующий пример кода.

|

import math var = 0.6 print(math.erf(var)) |

Примеры программ по методу erf() в Python

Пример 1. Программа, демонстрирующая работу метода erf()

|

import math a1 = 0.3 b1 = 0.9 c1 = 0.7 d1 = 0.2 print(«Value for parameter «, a1, » is «, math.erf(a1)) print(«Value for parameter «, b1, » is «, math.erf(b1)) print(«Value for parameter «, c1, » is «, math.erf(c1)) print(«Value for parameter «, d1, » is «, math.erf(d1)) |

Выход:

|

Value for parameter 0.3 is 0.3286267594591274 Value for parameter 0.9 is 0.796908212422832 Value for parameter 0.7 is 0.6778011938374183 Value for parameter 0.2 is 0.22270258921047847 |

В этом примере кода мы видели, что, передавая параметр vaild, который отличается для разных примеров, мы получаем желаемое решение метода erf().

Пример 2. Программа для передачи значения вне допустимого диапазона из функции и отображения вывода

См. следующий код.

|

import math x = ‘b’ print(math.erf(x)) |

Выход:

|

TypeError: must be real number, not str |

В этом примере мы видим, что при передаче параметра, который не имеет числового типа, функция выдает ошибку.

Python erfc() — это встроенный метод, определенный в математическом модуле, который используется для поиска дополнительной функции ошибок в точке x, если x — переданный параметр. Например, если x передается в качестве параметра в функцию erf(erf(x)), она возвращает дополнительную функцию ошибки.

Что такое функция erfc() в Python?

Функция Python math.erfc() возвращает дополнительную функцию ошибки в точке x. Функция ошибки также известна как функция ошибки Гаусса, и функция выдает ошибку, если в качестве параметра передается любое не числовое значение. Определяется как 1,0 – erf(x). Используется для большого значения x, если мы вычтем из 1, то это приведет к потере значимости.

Мы можем использовать математический модуль, импортировав его. После импорта мы используем для вызова этой функции статический объект.

Синтаксис

Здесь var — это переменная, для которой мы должны найти дополнительную функцию ошибки.

Параметры

Он принимает один параметр var, который принимает значения числового типа данных и выдает ошибку типа, если передается аргумент любого другого типа данных.

Возвращаемое значение

Он возвращает значение функции ошибки числа в типе данных float.

См. следующий код.

|

import math var = 0.6 print(math.erfc(var)) |

Примеры программ

Пример 1. Программа, показывающая работу метода erfc()

|

import math a1 = 0.3 b1 = 0.9 c1 = 0.7 d1 = 0.2 print(«Value for parameter «, a1, » is «, math.erfc(a1)) print(«Value for parameter «, b1, » is «, math.erfc(b1)) print(«Value for parameter «, c1, » is «, math.erfc(c1)) print(«Value for parameter «, d1, » is «, math.erfc(d1)) |

Выход:

|

Value for parameter 0.3 is 0.6713732405408726 Value for parameter 0.9 is 0.20309178757716786 Value for parameter 0.7 is 0.32219880616258156 Value for parameter 0.2 is 0.7772974107895215 |

В этом примере мы видели, что, передавая параметр vaild, который отличается для разных примеров, мы получаем желаемое решение метода erfc(), которое является дополнительным значением функции ошибок.

Пример 2. Передача значения вне допустимого диапазона из функции и отображения вывода

|

import math x = ‘b’ print(math.erfc(x)) |

Выход:

|

TypeError: must be real number, not str |

В этом примере мы видели, что при передаче параметра, который не имеет числового типа, функция выдает ошибку.

Дополнительная функция ошибок

Синтаксис

Описание

Примеры

Дополнительная функция ошибок для с плавающей точкой и символьных чисел

В зависимости от его аргументов, erfc может возвратить или точные символьные результаты с плавающей точкой.

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для этих чисел. Поскольку эти числа не являются символьными объектами, вы получаете результаты с плавающей точкой:

A = [erfc(1/2), erfc(1.41), erfc(sqrt(2))]

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для тех же чисел, преобразованных в символьные объекты. Для большинства символьных (точных) чисел, erfc отвечает на неразрешенные символьные звонки:

symA = [erfc(sym(1/2)), erfc(sym(1.41)), erfc(sqrt(sym(2)))]

symA = [ erfc(1/2), erfc(141/100), erfc(2^(1/2))]

Использование vpa аппроксимировать символьные результаты необходимым количеством цифр:

d = digits(10); vpa(symA) digits(d)

ans = [ 0.4795001222, 0.04614756064, 0.0455002639]

Функция ошибок для переменных и выражений

Для большинства символьных переменных и выражений, erfc отвечает на неразрешенные символьные звонки.

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для x и sin(x) + x*exp(x):

syms x f = sin(x) + x*exp(x); erfc(x) erfc(f)

ans = erfc(x) ans = erfc(sin(x) + x*exp(x))

Дополнительная функция ошибок для векторов и матриц

Если входной параметр является вектором или матрицей, erfc возвращает дополнительную функцию ошибок для каждого элемента того вектора или матрицы.

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для элементов матричного M и векторный V:

M = sym([0 inf; 1/3 -inf]); V = sym([1; -i*inf]); erfc(M) erfc(V)

ans =

[ 1, 0]

[ erfc(1/3), 2]

ans =

erfc(1)

1 + Inf*1i

Вычислите повторный интеграл дополнительной функции ошибок для элементов V и M, и целочисленный -1:

ans =

[ 2/pi^(1/2), 0]

[ (2*exp(-1/9))/pi^(1/2), 0]

ans =

(2*exp(-1))/pi^(1/2)

Inf

Специальные значения дополнительной функции ошибок

erfc возвращает специальные значения для конкретных параметров.

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для x = 0, x = ∞, и x = – ∞. Дополнительная функция ошибок имеет специальные значения для этих параметров:

[erfc(0), erfc(Inf), erfc(-Inf)]

Вычислите дополнительную функцию ошибок для комплексных бесконечностей. Использование sym преобразовывать комплексные бесконечности в символьные объекты:

[erfc(sym(i*Inf)), erfc(sym(-i*Inf))]

ans = [ 1 - Inf*1i, 1 + Inf*1i]

Обработка выражений, которые содержат дополнительную функцию ошибок

Много функций, такой как diff и int, может обработать выражения, содержащие erfc.

Вычислите первые и вторые производные дополнительной функции ошибок:

syms x diff(erfc(x), x) diff(erfc(x), x, 2)

ans = -(2*exp(-x^2))/pi^(1/2) ans = (4*x*exp(-x^2))/pi^(1/2)

Вычислите интегралы этих выражений:

syms x int(erfc(-1, x), x)

ans = x*erfc(x) - exp(-x^2)/pi^(1/2)

ans = (x^3*erfc(x))/6 - exp(-x^2)/(6*pi^(1/2)) +... (x*erfc(x))/4 - (x^2*exp(-x^2))/(6*pi^(1/2))

Постройте дополнительную функцию ошибок

Постройте дополнительную функцию ошибок на интервале от-5 до 5.

syms x fplot(erfc(x),[-5 5]) grid on

Входные параметры

свернуть все

X входной параметр

символьное число | символьная переменная | символьное выражение | символьная функция | символьный вектор | символьная матрица

Введите в виде символьного числа, переменной, выражения или функции, или как вектор или матрица символьных чисел, переменных, выражений или функций.

K — Введите представление целого числа, больше, чем -2

номер | символьное число | символьная переменная | символьное выражение | символьная функция | символьный вектор | символьная матрица

Введите представление целого числа, больше, чем -2В виде номера, символьного числа, переменной, выражения или функции. Это аргументы может также быть вектором или матрицей чисел, символьных чисел, переменных, выражений или функций.

Больше о

свернуть все

Дополнительная функция ошибок

Следующий интеграл задает дополнительную функцию ошибок:

Здесь erf(x) функция ошибок.

Повторный интеграл дополнительной функции ошибок

Следующий интеграл является повторным интегралом дополнительной функции ошибок:

Здесь, erfc(0,x)=erfc(x).

Советы

-

Вызов

erfcдля номера, который не является символьным объектом, вызывает MATLAB®erfcфункция. Эта функция принимает действительные аргументы только. Если вы хотите вычислить дополнительную функцию ошибок для комплексного числа, используйтеsymпреобразовывать тот номер в символьный объект, и затем вызыватьerfcдля того символьного объекта. -

Для большинства символьных (точных) чисел,

erfcотвечает на неразрешенные символьные звонки. Можно аппроксимировать такие результаты использованием чисел с плавающей запятойvpa. -

По крайней мере один входной параметр должен быть скаляром, или оба аргумента должны быть векторами или матрицами, одного размера. Если один входной параметр является скаляром, и другой является вектором или матрицей, то

erfcрасширяет скаляр в вектор или матрицу одного размера с другим аргументом со всеми элементами, равными тому скаляру.

Алгоритмы

Тулбокс может упростить выражения, которые содержат функции ошибок и их инверсии. Для вещественных значений x, тулбокс применяет эти правила упрощения:

-

erfinv(erf(x)) = erfinv(1 - erfc(x)) = erfcinv(1 - erf(x)) = erfcinv(erfc(x)) = x -

erfinv(-erf(x)) = erfinv(erfc(x) - 1) = erfcinv(1 + erf(x)) = erfcinv(2 - erfc(x)) = -x

Для любого значения x, система применяет эти правила упрощения:

-

erfcinv(x) = erfinv(1 - x) -

erfinv(-x) = -erfinv(x) -

erfcinv(2 - x) = -erfcinv(x) -

erf(erfinv(x)) = erfc(erfcinv(x)) = x -

erf(erfcinv(x)) = erfc(erfinv(x)) = 1 - x

Ссылки

[1] Gautschi, W. “Функция ошибок и Интегралы Френели”. Руководство Математических функций с Формулами, Графиками и Математическими Таблицами. (М. Абрамовиц и я. А. Стегун, редакторы). Нью-Йорк: Дувр, 1972.

Представленный в R2011b

Посетите Центр обучения

Используете продукты Google (например, Google Документы) на работе или в учебном заведении? Мы подготовили для вас полезные советы, руководства и шаблоны. Узнайте, как работать с файлами Office, не устанавливая MS Office, как создавать динамические планы проектов и командные календари, использовать автосортировку писем и решать другие задачи.

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}Pr[Xleq L]&={frac {1}{2}}+{frac {1}{2}}operatorname {erf} {frac {L-mu }{{sqrt {2}}sigma }}&approx Aexp left(-Bleft({frac {L-mu }{sigma }}right)^{2}right)end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f3cb760eaf336393db9fd0bb12c4465655a27de8)

![{displaystyle Pr[Xleq L]leq Aexp(-Bln {k})={frac {A}{k^{B}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2baadea015e20a45d1034fd88eed861e7fcce178)

![{displaystyle {begin{aligned}Pr[L_{a}leq Xleq L_{b}]&=int _{L_{a}}^{L_{b}}{frac {1}{{sqrt {2pi }}sigma }}exp left(-{frac {(x-mu )^{2}}{2sigma ^{2}}}right),mathrm {d} x&={frac {1}{2}}left(operatorname {erf} {frac {L_{b}-mu }{{sqrt {2}}sigma }}-operatorname {erf} {frac {L_{a}-mu }{{sqrt {2}}sigma }}right).end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cd2214f0db2c1d36075815825b616501175c6283)