Когда-нибудь шарик, несомненно, сменит «цветовую ориентацию». Вероятность, что сто раз подряд выпадет «чёрное», чрезвычайно низка. Даже вероятность десяти таких выпадений — всего лишь 1:1024. Но при этом, вот ведь парадокс, вероятность выпадения «чёрного» и «красного» (или, скажем, «орла» и «решки» при игре в орлянку) в каждом конкретном случае… всегда 50 на 50!

Когнитивное искажение под названием «ошибка игрока» — напоминание о том, что нельзя забывать о Его Величестве Случае даже тогда, когда закономерность нам кажется очевидной. Недооценка случайностей приводит к болезненным последствиям:

Существует несколько типичных ошибок, которые поколение за поколением допускают игроки казино и все, кто рассчитывают на удачу — в том числе трейдеры авантюрного склада и трейдеры-новички. К классике заблуждений относится так называемая ошибка игрока, заключающаяся в завышенных ожиданиях повторения или изменения ситуации. Проще говоря, это ожидание «красного» после серии «чёрного»: нам кажется, чем чаще шарик в рулетке попадает на один цвет, тем больше шансов, что в следующий раз он попадёт на другой.

- игроки в казино теряют миллионы, когда 26 раз выпадает «красное»;

- покеристы рвут на себе волосы, не в состоянии справиться со стрессом в период даунстриков;

- трейдеры сливают капиталы в игре «по рынку», надеясь заработать быстро и много в условиях хаотичного движения цен.

Проблема усугубляется наложением на «ошибку игрока» иллюзии контроля, боязни убытков и банальной жадности. Всё вместе это создаёт гремучую смесь, от которой так часто взлетают на воздух все мечты о заработке на трейдинге.

Давайте же разберёмся, как именно недооценка роли случайности губит карьеры трейдеров.

Ошибка зрелых шансов и проблема недокапитализации

Как уже говорилось, вероятность последовательного выпадения «чёрного» 10 раз подряд составляет 1:1024. На этом математическом факте строится стратегия удвоения ставок, или система мартингейла, которую некоторые недобросовестные инфобизнесмены продают как «гарантию» обмана казино. Другие действуют хитрее: предоставляют эту «суперстратегию» бесплатно при условии регистрации в онлайн-казино по их ссылке. Казалось бы, в чём их выгода, если обладатель «волшебной стратегии» будет выигрывать, ведь тогда партнёрская программа не принесёт ни цента? Да всё просто: большинство игроков всё равно останутся в проигрыше.

Система мартингейла известна с XVIII века. Многие игроки и сами её «изобретают», немного поиграв в рулетку. (А кое-кто платит инфобизнесменам за эту «инновационную суперстратегию», подтверждая поговорку «лох не мамонт — не вымрет».) Против «ошибки игрока» приверженцы системы мартингейла выдвигают следующий аргумент: мы же играем сериями, поэтому должна работать формула, подсчитывающая именно последовательное выпадение того или иного цвета подряд.

Проблема в том, что гарантии срабатывания этой формулы именно в вашем конкретном случае нет.

«Ошибка игрока» также называется «ошибкой зрелых шансов» (подразумевается, что с каждым выпадением цвета X подряд шансы выпадения противоположного цвета Y «вызревают», повышаются). Но есть у этой ошибки и ещё одно название — «ложный вывод Монте-Карло». Оно было дано в память о шоке, который настиг игроков одного из казино Монте-Карло 18 августа 1913 года: шарик 26 раз подряд угодил на «чёрное»!

Нетрудно подсчитать, используя метод геометрической прогрессии, что никаких капиталов не хватит, дабы применить при таком раскладе метод мартингейла. Более того: сотни тысяч и даже миллионы франков теряли люди, которые вступили в игру после того, как шарик уже попал на «чёрное» с дюжину раз. Им казалось, что уж в следующий-то раз наверняка будет «красное»!

А уж сколько раз в казино наблюдались серии из 8—12 попаданий на один цвет, и говорить не стоит.

Вот тут и вступает в действие проблема несовпадения намерений и возможностей, теории и реальности. Она выражается в недокапитализации. Если бы у человека был безлимитный кредит, «ошибка игрока» стала бы ему не страшна. Но даже если поставить в первый раз $1000, то в 8-й придётся выкладывать уже $128 000.

Та же самая проблема недокапитализации подстерегает и трейдера, который нарушает принципы личного риск-менеджмента. Постоянно повышая ставки в надежде отыграться, он попросту сливает депозит.

Иллюзия контроля

Что заставляет трейдера поддаться этому когнитивному искажению? Иллюзия контроля, особенно часто возникающая при гипнотизировании графиков. Трейдеры, склонные неотрывно следить за хаотическими колебаниями цен, часто начинают торговать не по системе, а «по рынку». К сожалению, рынок жесток и непредсказуем, и поддавшиеся иллюзии контроля трейдеры совершают ту самую «ошибку игрока»: видят закономерности там, где их нет.

Эффект этого когнитивного искажения усиливается, когда трейдер особенно сильно заинтересован в положительном результате: он выискивает сигналы (включая внебиржевые новости), которые якобы подтверждают его выводы о поведении тренда.

Страшно хочется отыграться

Интересный факт: при ограниченности ресурсов шанс проиграться вчистую иногда выше, чем шанс дождаться, когда в серии ставок наконец сработает формула последовательного выпадения нужного цвета подряд. Если капитал невелик, то каждое удвоение повышает риск остаться без штанов!

Точно так же и в трейдинге: чем меньше депозит, тем выше шансы его слить при торговле «по рынку».

Но даже понимая риск разорения, игроки и трейдеры-авантюристы упорно продолжают повышать ставки при проигрыше. Вместо того чтобы минимизировать риски, авантюрные натуры их увеличивают! Почему? Да всё просто: такими игроками и трейдерами движут страх и жадность. Им невыносимо думать, что уже вложенные деньги придётся записать в убытки.

Даунстрик: покеристы и трейдеры

Неумение смириться с убытками усиливает негативный эффект от «ошибки игрока». Профессионалы же знают: убытки на поле, где царит случайность, неизбежны. И, вопреки надеждам на быструю смену «чёрного» и «красного», череда неудач может затянуться. В покере такое явление называют «даунстрик» — невозможность переломить негативный тренд при использовании привычных стратегий и приёмов. Вот просто не везёт, и всё — карты не те!

У трейдеров тоже случаются периоды даунстриков: убыточными могут быть несколько месяцев подряд. Спасают трейдера в эти периоды системная торговля, которая в итоге всё равно нивелирует случайный риск, чёткое следование принципам риск-менеджмента, финансовая подушка и крепкие нервы. Только так можно переждать чёрную полосу. Когда она закончится — никому неизвестно, а попытки предугадать приводят к той самой «ошибке игрока».

Поэтому… расслабляемся и продолжаем придерживаться системы, которая позволяет минимизировать риск в ожидании крупного профита. И всегда помним: важен не краткосрочный взлёт, а долгосрочный успех.

подписаться на канал Telegram

Фальшивая интуиция

Какими бы ни были причины такой фальшивой интуиции, исследования показывают: ошибка игрока может иметь самые серьезные последствия — не только в казино.

Возьмем, к примеру, торговлю на фондовом рынке. Курсы акций часто колеблются в небольших пределах — причем достаточно случайно. Как показал Маттиас Пелстер из Падерборнского университета (Германия), инвесторы могут принимать решения на основе убежденности в том, что цены на акции скоро выровняются. То есть, как и те невезучие итальянцы, они не верят в вероятность колебаний в одну и ту же сторону. И на этом проигрывают.

Ошибка игрока может превратиться в серьезнейшую проблему в тех профессиональных сферах, в которых требуется взвешенное, непредвзятое суждение.

Группа исследователей в США недавно обнаружила, что ложный вывод Монте-Карло влияет на решения судей, предоставляющих убежище беженцам из других стран.

Если рассуждать логически, то порядок рассматриваемых дел не должен иметь никакого значения. Но судьи предоставляли убежище с меньшей вероятностью (до 5,5%), если перед этим уже приняли такое решение в отношении двух соискателей подряд.

Сознательно или нет, они, судя по всему, думали, что три положительных решения подряд — это слишком много.

Затем исследователи проанализировали действия сотрудников банка, рассматривающих заявления о предоставлении кредита. И тут тоже играл роль порядок решений по заявлениям. Отрицательные решения принимались с вероятностью на 8% выше, когда перед этим уже было вынесено два или больше положительных решения. И наоборот.

И наконец, ученые проанализировали действия арбитров матчей Главной лиги бейсбола — и тут тоже обнаружили влияние ложного вывода Монте-Карло на решения спортивных судей. Причем на такие решения, от которых зависел исход матча!

Одна из соавторов исследования, Келли Шу, рассказывает, что ее поразили такие результаты. «Это же профессионалы, принятие таких решений — их главное занятие», — говорит она. И тем не менее…

Более знакомого нам футбола это тоже касается — например, когда в решающем матче дело доходит до серии пенальти. Мячу, чтобы залететь после удара в ворота, требуется 0,2-0,3 секунды.

Голкипер должен очень быстро решить, прыгать ли ему в угол одновременно с ударом или оставаться в центре ворот, надеясь на свою реакцию. По словам Симчи Авугоса из израильского Университета имени Бен-Гуриона, решение вратаря — это фактически азартная игра.

Но, как и работники банка, как и судьи, предоставляющие убежище, вратари чаще всего не верят в то, что все удары подряд могут быть в один и тот же угол.

Коллектив исследователей под руководством Авугоса недавно проанализировал, как пробивались серии пенальти во время финальных матчей Кубка мира и чемпионата Европы. На основе того, что они обнаружили, ученые предлагают футболистам пользоваться тенденцией и продолжать бить в один и тот же угол — ведь вратарь не поверит, что все удары будут в одно место!

И хотя наша повседневная жизнь далека от ситуаций, когда на кон поставлено все, Келли Шу считает, что пресловутая ошибка игрока присутствует практически во всех сферах жизни — даже если мы сами и не осознаем, что прибегаем к подобным вероятностным суждениям.

Шу приводит в пример процесс набора персонала. Если представители работодателя, проводящие собеседование, только что сделали выбор в пользу отличного кандидата, они подсознательно не ожидают, что вслед за ним появится еще один, не менее выдающийся. И этот следующий получит от них более жесткие оценки.

То же самое относится и к учителям, проверяющим сочинения, говорит она. Или, например, вы работник издательства, ищущий новые романы для публикации. Вы можете отказаться от рукописи будущей Джоан Роулинг только на том основании, что уже подписали контракт на пару блестящих рукописей.

Какой бы ни была ваша профессия, вам следует помнить о том хаосе, который породила «лихорадка 53».

Одно и то же событие может происходить много раз подряд, независимо от того, что было до него. И нам стоит призвать на помощь всю свою рациональность и признать: наша интуиция часто подсказывает нам совершенно неверные действия.

На основестатьи Дэвида Робсона. Робсон — автор книги «Ловушка интеллекта: почему умные люди делают глупости».

Ошибка игрока или ложный вывод Монте-Карло

и

Психолог, гештальт-терапевт. Консультирует с 2015 года

- В чем заключается ошибка игрока?

- Что делать с ошибкой игрока в реальной жизни?

Чтобы понять, что такое ошибка игрока, или ложный вывод Монте-Карло, представьте, что вы в казино, играете в рулетку. Вот выпадет красное, черное, красное, красное, черное, черное, черное, черное, черное, черное… Какое выпадет следующим? Кажется ли вам, что с каждым черным увеличивается шанс, что следующим будет красное? Если да, то вы подвержены ошибке игрока. Почему и что с этим делать, мы расскажем ниже.

В чем заключается ошибка игрока?

Сначала представим, что от рулетки вы пересели за карточный стол. Перед вами колода из 36 карт, и вам надо угадать цвет масти. Расклад тот же – красное, черное, красное, красное, черное, черное, черное, черное, черное, черное… Кажется ли вам, что с каждым черным увеличивается шанс, что следующим будет красное? В данном случае это логично – число карт ограниченно и мы точно знаем, сколько черных и красных. Чем больше черных карт открыто на столе, тем больше красных в колоде, а следовательно, растет шанс, что следующая будет красной.

Конечно, шанс, что черное выпадет 50 раз подряд, чрезвычайно мал, но он все же есть. Ошибка игрока говорит о том, что в некоторых ситуациях нужно фокусироваться на конкретном событии в череде случайностей, а не на цепочке событий. Из-за того что мы буквально инстинктивно стараемся проанализировать цепочку целиком, мы делаем неверные выводы и идем по неправильному пути. При этом такая ловушка мышления проявляет себя далеко не только в казино или в других азартных играх, но и в быту и в работе.

Тренируйте память, внимание и другие софт-скиллс на Викиум.ру

Что делать с ошибкой игрока в реальной жизни?

Чтобы избежать проблем, связанных с этим когнитивным искажением, надо определиться, влияют ли результаты предыдущих событий на текущее. Если влияния нет, не нужно на него полагаться и делать на его основе какие-либо выводы. Если оно есть, но вы его не видите, его необходимо отследить.

Например, вы подбираете сотрудников в свою компанию. Вы побеседовали уже с 10 кандидатами на вакансию, и это не те, кого вы ищете. Банальное невезение? Вполне возможно. А может быть, неправильно составлен текст вакансии. Таким образом, не будет лишним проверить описание требований и обязанностей, соотнести зарплату со средней по рынку, подумать, как подчеркнуть достоинства компании и места, и т.д.

Скажем, вы ищете работу и получили уже три прекрасных предложения. И когда вам приходит четвертое, вы наверняка отнесетесь к нему с предубеждением: «Да ну, там не будет ничего хорошего, ведь не может же так везти». В результате вы станете придираться даже к мелочам, хотя на самом деле этот оффер может быть лучше предыдущих. В данном случае каждое предложение о работе в целом не связано с предыдущими офферами, только с собеседованиями и вашим резюме. Поэтому не выстраивайте взаимосвязь между самими предложениями, рассматривайте каждое из них в отдельности, а следовательно, не игнорируйте четвертое.

Поделиться статьей:

The gambler’s fallacy, also known as the Monte Carlo fallacy or the fallacy of the maturity of chances, is the incorrect belief that, if a particular event occurs more frequently than normal during the past, it is less likely to happen in the future (or vice versa), when it has otherwise been established that the probability of such events does not depend on what has happened in the past. Such events, having the quality of historical independence, are referred to as statistically independent. The fallacy is commonly associated with gambling, where it may be believed, for example, that the next dice roll is more than usually likely to be six because there have recently been fewer than the expected number of sixes.

The term «Monte Carlo fallacy» originates from the best known example of the phenomenon, which occurred in the Monte Carlo Casino in 1913.[1]

Examples[edit]

Coin toss[edit]

Over time, the proportion of red/blue coin tosses approaches 50-50, but the difference does not systematically decrease to zero.

The gambler’s fallacy can be illustrated by considering the repeated toss of a fair coin. The outcomes in different tosses are statistically independent and the probability of getting heads on a single toss is 1/2 (one in two). The probability of getting two heads in two tosses is 1/4 (one in four) and the probability of getting three heads in three tosses is 1/8 (one in eight). In general, if Ai is the event where toss i of a fair coin comes up heads, then:

.

If after tossing four heads in a row, the next coin toss also came up heads, it would complete a run of five successive heads. Since the probability of a run of five successive heads is 1/32 (one in thirty-two), a person might believe that the next flip would be more likely to come up tails rather than heads again. This is incorrect and is an example of the gambler’s fallacy. The event «5 heads in a row» and the event «first 4 heads, then a tails» are equally likely, each having probability 1/32. Since the first four tosses turn up heads, the probability that the next toss is a head is:

.

While a run of five heads has a probability of 1/32 = 0.03125 (a little over 3%), the misunderstanding lies in not realizing that this is the case only before the first coin is tossed. After the first four tosses in this example, the results are no longer unknown, so their probabilities are at that point equal to 1 (100%). The probability of a run of coin tosses of any length continuing for one more toss is always 0.5. The reasoning that a fifth toss is more likely to be tails because the previous four tosses were heads, with a run of luck in the past influencing the odds in the future, forms the basis of the fallacy.

Why the probability is 1/2 for a fair coin[edit]

If a fair coin is flipped 21 times, the probability of 21 heads is 1 in 2,097,152. The probability of flipping a head after having already flipped 20 heads in a row is 1/2. Assuming a fair coin:

- The probability of 20 heads, then 1 tail is 0.520 × 0.5 = 0.521

- The probability of 20 heads, then 1 head is 0.520 × 0.5 = 0.521

The probability of getting 20 heads then 1 tail, and the probability of getting 20 heads then another head are both 1 in 2,097,152. When flipping a fair coin 21 times, the outcome is equally likely to be 21 heads as 20 heads and then 1 tail. These two outcomes are equally as likely as any of the other combinations that can be obtained from 21 flips of a coin. All of the 21-flip combinations will have probabilities equal to 0.521, or 1 in 2,097,152. Assuming that a change in the probability will occur as a result of the outcome of prior flips is incorrect because every outcome of a 21-flip sequence is as likely as the other outcomes. In accordance with Bayes’ theorem, the likely outcome of each flip is the probability of the fair coin, which is 1/2.

Other examples[edit]

The fallacy leads to the incorrect notion that previous failures will create an increased probability of success on subsequent attempts. For a fair 16-sided die, the probability of each outcome occurring is 1/16 (6.25%). If a win is defined as rolling a 1, the probability of a 1 occurring at least once in 16 rolls is:

The probability of a loss on the first roll is 15/16 (93.75%). According to the fallacy, the player should have a higher chance of winning after one loss has occurred. The probability of at least one win is now:

By losing one toss, the player’s probability of winning drops by two percentage points. With 5 losses and 11 rolls remaining, the probability of winning drops to around 0.5 (50%). The probability of at least one win does not increase after a series of losses; indeed, the probability of success actually decreases, because there are fewer trials left in which to win. The probability of winning will eventually be equal to the probability of winning a single toss, which is 1/16 (6.25%) and occurs when only one toss is left.

Reverse position[edit]

After a consistent tendency towards tails, a gambler may also decide that tails has become a more likely outcome. This is a rational and Bayesian conclusion, bearing in mind the possibility that the coin may not be fair; it is not a fallacy. Believing the odds to favor tails, the gambler sees no reason to change to heads. However it is a fallacy that a sequence of trials carries a memory of past results which tend to favor or disfavor future outcomes.

The inverse gambler’s fallacy described by Ian Hacking is a situation where a gambler entering a room and seeing a person rolling a double six on a pair of dice may erroneously conclude that the person must have been rolling the dice for quite a while, as they would be unlikely to get a double six on their first attempt.

Retrospective gambler’s fallacy[edit]

Researchers have examined whether a similar bias exists for inferences about unknown past events based upon known subsequent events, calling this the «retrospective gambler’s fallacy».[2]

An example of a retrospective gambler’s fallacy would be to observe multiple successive «heads» on a coin toss and conclude from this that the previously unknown flip was «tails».[2] Real world examples of retrospective gambler’s fallacy have been argued to exist in events such as the origin of the Universe. In his book Universes, John Leslie argues that «the presence of vastly many universes very different in their characters might be our best explanation for why at least one universe has a life-permitting character».[3] Daniel M. Oppenheimer and Benoît Monin argue that «In other words, the ‘best explanation’ for a low-probability event is that it is only one in a multiple of trials, which is the core intuition of the reverse gambler’s fallacy.»[2] Philosophical arguments are ongoing about whether such arguments are or are not a fallacy, arguing that the occurrence of our universe says nothing about the existence of other universes or trials of universes.[4][5] Three studies involving Stanford University students tested the existence of a retrospective gamblers’ fallacy. All three studies concluded that people have a gamblers’ fallacy retrospectively as well as to future events.[2] The authors of all three studies concluded their findings have significant «methodological implications» but may also have «important theoretical implications» that need investigation and research, saying «[a] thorough understanding of such reasoning processes requires that we not only examine how they influence our predictions of the future, but also our perceptions of the past.»[2]

Childbirth[edit]

In 1796, Pierre-Simon Laplace described in A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities the ways in which men calculated their probability of having sons: «I have seen men, ardently desirous of having a son, who could learn only with anxiety of the births of boys in the month when they expected to become fathers. Imagining that the ratio of these births to those of girls ought to be the same at the end of each month, they judged that the boys already born would render more probable the births next of girls.» The expectant fathers feared that if more sons were born in the surrounding community, then they themselves would be more likely to have a daughter. This essay by Laplace is regarded as one of the earliest descriptions of the fallacy.[6] Likewise, after having multiple children of the same sex, some parents may erroneously believe that they are due to have a child of the opposite sex.

Monte Carlo Casino[edit]

Perhaps the most famous example of the gambler’s fallacy occurred in a game of roulette at the Monte Carlo Casino on August 18, 1913, when the ball fell in black 26 times in a row. This was an extremely uncommon occurrence: the probability of a sequence of either red or black occurring 26 times in a row is (18/37)26-1 or around 1 in 66.6 million, assuming the mechanism is unbiased. Gamblers lost millions of francs betting against black, reasoning incorrectly that the streak was causing an imbalance in the randomness of the wheel, and that it had to be followed by a long streak of red.[1]

Non-examples[edit]

Non-independent events[edit]

The gambler’s fallacy does not apply when the probability of different events is not independent. In such cases, the probability of future events can change based on the outcome of past events, such as the statistical permutation of events. An example is when cards are drawn from a deck without replacement. If an ace is drawn from a deck and not reinserted, the next card drawn is less likely to be an ace and more likely to be of another rank. The probability of drawing another ace, assuming that it was the first card drawn and that there are no jokers, has decreased from 4/52 (7.69%) to 3/51 (5.88%), while the probability for each other rank has increased from 4/52 (7.69%) to 4/51 (7.84%). This effect allows card counting systems to work in games such as blackjack.

Bias[edit]

In most illustrations of the gambler’s fallacy and the reverse gambler’s fallacy, the trial (e.g. flipping a coin) is assumed to be fair. In practice, this assumption may not hold. For example, if a coin is flipped 21 times, the probability of 21 heads with a fair coin is 1 in 2,097,152. Since this probability is so small, if it happens, it may well be that the coin is somehow biased towards landing on heads, or that it is being controlled by hidden magnets, or similar.[7] In this case, the smart bet is «heads» because Bayesian inference from the empirical evidence — 21 heads in a row — suggests that the coin is likely to be biased toward heads. Bayesian inference can be used to show that when the long-run proportion of different outcomes is unknown but exchangeable (meaning that the random process from which the outcomes are generated may be biased but is equally likely to be biased in any direction) and that previous observations demonstrate the likely direction of the bias, the outcome which has occurred the most in the observed data is the most likely to occur again.[8]

For example, if the a priori probability of a biased coin is say 1%, and assuming that such a biased coin would come down heads say 60% of the time, then after 21 heads the probability of a biased coin has increased to about 32%.

The opening scene of the play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard discusses these issues as one man continually flips heads and the other considers various possible explanations.

Changing probabilities[edit]

If external factors are allowed to change the probability of the events, the gambler’s fallacy may not hold. For example, a change in the game rules might favour one player over the other, improving his or her win percentage. Similarly, an inexperienced player’s success may decrease after opposing teams learn about and play against their weaknesses. This is another example of bias.

Psychology[edit]

Origins[edit]

The gambler’s fallacy arises out of a belief in a law of small numbers, leading to the erroneous belief that small samples must be representative of the larger population. According to the fallacy, streaks must eventually even out in order to be representative.[9] Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman first proposed that the gambler’s fallacy is a cognitive bias produced by a psychological heuristic called the representativeness heuristic, which states that people evaluate the probability of a certain event by assessing how similar it is to events they have experienced before, and how similar the events surrounding those two processes are.[10][9] According to this view, «after observing a long run of red on the roulette wheel, for example, most people erroneously believe that black will result in a more representative sequence than the occurrence of an additional red»,[10] so people expect that a short run of random outcomes should share properties of a longer run, specifically in that deviations from average should balance out. When people are asked to make up a random-looking sequence of coin tosses, they tend to make sequences where the proportion of heads to tails stays closer to 0.5 in any short segment than would be predicted by chance, a phenomenon known as insensitivity to sample size.[11] Kahneman and Tversky interpret this to mean that people believe short sequences of random events should be representative of longer ones.[9] The representativeness heuristic is also cited behind the related phenomenon of the clustering illusion, according to which people see streaks of random events as being non-random when such streaks are actually much more likely to occur in small samples than people expect.[12]

The gambler’s fallacy can also be attributed to the mistaken belief that gambling, or even chance itself, is a fair process that can correct itself in the event of streaks, known as the just-world hypothesis.[13] Other researchers believe that belief in the fallacy may be the result of a mistaken belief in an internal locus of control. When a person believes that gambling outcomes are the result of their own skill, they may be more susceptible to the gambler’s fallacy because they reject the idea that chance could overcome skill or talent.[14]

Variations[edit]

Some researchers believe that it is possible to define two types of gambler’s fallacy: type one and type two. Type one is the classic gambler’s fallacy, where individuals believe that a particular outcome is due after a long streak of another outcome. Type two gambler’s fallacy, as defined by Gideon Keren and Charles Lewis, occurs when a gambler underestimates how many observations are needed to detect a favorable outcome, such as watching a roulette wheel for a length of time and then betting on the numbers that appear most often. For events with a high degree of randomness, detecting a bias that will lead to a favorable outcome takes an impractically large amount of time and is very difficult, if not impossible, to do.[15] The two types differ in that type one wrongly assumes that gambling conditions are fair and perfect, while type two assumes that the conditions are biased, and that this bias can be detected after a certain amount of time.

Another variety, known as the retrospective gambler’s fallacy, occurs when individuals judge that a seemingly rare event must come from a longer sequence than a more common event does. The belief that an imaginary sequence of die rolls is more than three times as long when a set of three sixes is observed as opposed to when there are only two sixes. This effect can be observed in isolated instances, or even sequentially. Another example would involve hearing that a teenager has unprotected sex and becomes pregnant on a given night, and concluding that she has been engaging in unprotected sex for longer than if we hear she had unprotected sex but did not become pregnant, when the probability of becoming pregnant as a result of each intercourse is independent of the amount of prior intercourse.[16]

Relationship to hot-hand fallacy[edit]

Another psychological perspective states that gambler’s fallacy can be seen as the counterpart to basketball’s hot-hand fallacy, in which people tend to predict the same outcome as the previous event — known as positive recency — resulting in a belief that a high scorer will continue to score. In the gambler’s fallacy, people predict the opposite outcome of the previous event — negative recency — believing that since the roulette wheel has landed on black on the previous six occasions, it is due to land on red the next. Ayton and Fischer have theorized that people display positive recency for the hot-hand fallacy because the fallacy deals with human performance, and that people do not believe that an inanimate object can become «hot.»[17] Human performance is not perceived as random, and people are more likely to continue streaks when they believe that the process generating the results is nonrandom.[18] When a person exhibits the gambler’s fallacy, they are more likely to exhibit the hot-hand fallacy as well, suggesting that one construct is responsible for the two fallacies.[14]

The difference between the two fallacies is also found in economic decision-making. A study by Huber, Kirchler, and Stockl in 2010 examined how the hot hand and the gambler’s fallacy are exhibited in the financial market. The researchers gave their participants a choice: they could either bet on the outcome of a series of coin tosses, use an expert opinion to sway their decision, or choose a risk-free alternative instead for a smaller financial reward. Participants turned to the expert opinion to make their decision 24% of the time based on their past experience of success, which exemplifies the hot-hand. If the expert was correct, 78% of the participants chose the expert’s opinion again, as opposed to 57% doing so when the expert was wrong. The participants also exhibited the gambler’s fallacy, with their selection of either heads or tails decreasing after noticing a streak of either outcome. This experiment helped bolster Ayton and Fischer’s theory that people put more faith in human performance than they do in seemingly random processes.[19]

Neurophysiology[edit]

While the representativeness heuristic and other cognitive biases are the most commonly cited cause of the gambler’s fallacy, research suggests that there may also be a neurological component. Functional magnetic resonance imaging has shown that after losing a bet or gamble, known as riskloss, the frontoparietal network of the brain is activated, resulting in more risk-taking behavior. In contrast, there is decreased activity in the amygdala, caudate, and ventral striatum after a riskloss. Activation in the amygdala is negatively correlated with gambler’s fallacy, so that the more activity exhibited in the amygdala, the less likely an individual is to fall prey to the gambler’s fallacy. These results suggest that gambler’s fallacy relies more on the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive, goal-directed processes, and less on the brain areas that control affective decision-making.

The desire to continue gambling or betting is controlled by the striatum, which supports a choice-outcome contingency learning method. The striatum processes the errors in prediction and the behavior changes accordingly. After a win, the positive behavior is reinforced and after a loss, the behavior is conditioned to be avoided. In individuals exhibiting the gambler’s fallacy, this choice-outcome contingency method is impaired, and they continue to make risks after a series of losses.[20]

Possible solutions[edit]

The gambler’s fallacy is a deep-seated cognitive bias and can be very hard to overcome. Educating individuals about the nature of randomness has not always proven effective in reducing or eliminating any manifestation of the fallacy. Participants in a study by Beach and Swensson in 1967 were shown a shuffled deck of index cards with shapes on them, and were instructed to guess which shape would come next in a sequence. The experimental group of participants was informed about the nature and existence of the gambler’s fallacy, and were explicitly instructed not to rely on run dependency to make their guesses. The control group was not given this information. The response styles of the two groups were similar, indicating that the experimental group still based their choices on the length of the run sequence. This led to the conclusion that instructing individuals about randomness is not sufficient in lessening the gambler’s fallacy.[21]

An individual’s susceptibility to the gambler’s fallacy may decrease with age. A study by Fischbein and Schnarch in 1997 administered a questionnaire to five groups: students in grades 5, 7, 9, 11, and college students specializing in teaching mathematics. None of the participants had received any prior education regarding probability. The question asked was: «Ronni flipped a coin three times and in all cases heads came up. Ronni intends to flip the coin again. What is the chance of getting heads the fourth time?» The results indicated that as the students got older, the less likely they were to answer with «smaller than the chance of getting tails», which would indicate a negative recency effect. 35% of the 5th graders, 35% of the 7th graders, and 20% of the 9th graders exhibited the negative recency effect. Only 10% of the 11th graders answered this way, and none of the college students did. Fischbein and Schnarch theorized that an individual’s tendency to rely on the representativeness heuristic and other cognitive biases can be overcome with age.[22]

Another possible solution comes from Roney and Trick, Gestalt psychologists who suggest that the fallacy may be eliminated as a result of grouping. When a future event such as a coin toss is described as part of a sequence, no matter how arbitrarily, a person will automatically consider the event as it relates to the past events, resulting in the gambler’s fallacy. When a person considers every event as independent, the fallacy can be greatly reduced.[23]

Roney and Trick told participants in their experiment that they were betting on either two blocks of six coin tosses, or on two blocks of seven coin tosses. The fourth, fifth, and sixth tosses all had the same outcome, either three heads or three tails. The seventh toss was grouped with either the end of one block, or the beginning of the next block. Participants exhibited the strongest gambler’s fallacy when the seventh trial was part of the first block, directly after the sequence of three heads or tails. The researchers pointed out that the participants that did not show the gambler’s fallacy showed less confidence in their bets and bet fewer times than the participants who picked with the gambler’s fallacy. When the seventh trial was grouped with the second block, and was perceived as not being part of a streak, the gambler’s fallacy did not occur.

Roney and Trick argued that instead of teaching individuals about the nature of randomness, the fallacy could be avoided by training people to treat each event as if it is a beginning and not a continuation of previous events. They suggested that this would prevent people from gambling when they are losing, in the mistaken hope that their chances of winning are due to increase based on an interaction with previous events.

Users[edit]

Types of users[edit]

Within a real-world setting, numerous studies have uncovered that for various decision makers placed in high stakes scenarios, it is likely they will reflect some degree of strong negative autocorrelation in their judgement.

Asylum judges[edit]

In a study aimed at discovering if the negative autocorrelation that exists with the gambler’s fallacy existed in the decision made by U.S. asylum judges, results showed that after two successive asylum grants, a judge would be 5.5% less likely to approve a third grant.[24]

Baseball umpires[edit]

In the game of baseball, decisions are made every minute. One particular decision made by umpires which is often subject to scrutiny is the ‘strike zone’ decision. Whenever a batter does not swing, the umpire must decide if the ball was within a fair region for the batter, known as the strike zone. If outside of this zone, the ball does not count towards outing the batter. In a study of over 12,000 games, results showed that umpires are 1.3% less likely to call a strike if the previous two balls were also strikes.[24]

Loan officers[edit]

In the decision making of loan officers, it can be argued that monetary incentives are a key factor in biased decision making – making it hard to examine the gambler’s fallacy effect. However, research shows that loan officers who are not incentivised by monetary gain are 8% less likely to approve a loan if they approved one for the previous client.[25]

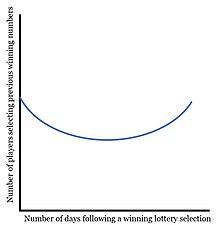

Lottery players[edit]

The effect of gambler’s fallacy on lottery selections, based on studies by Dek Terrell. After winning numbers are drawn, lottery players respond by reducing the number of times they select those numbers in following draws. This effect slowly corrects over time, as players become less affected by the fallacy.[26]

Lottery play and jackpots entice gamblers around the globe, with the biggest decision for hopeful winners being what numbers to pick. While most people will have their own strategy, evidence shows that after a number is selected as a winner in the current draw, the same number will experience a significant drop in selections in the following lottery. A popular study by Charles Clotfelter and Philip Cook, investigated this effect in 1991, where they concluded bettors would cease to select numbers immediately after they were selected — ultimately recovering selection popularity within three months.[27] Soon after, a 1994 study was constructed by Dek Terrell to test the findings of Clotfelter and Cook. The key change in Terrell’s study was the examination of a pari-mutuel lottery in which, a number selected with lower total wagers placed on it will result in a higher pay-out. While this examination did conclude that players in both types of lotteries exhibited behaviour in-line with the Gambler’s fallacy theory, those who took part in pari-mutuel betting seemed to be less influenced.[26]

Table 1. Percentage change in numbers selected by lottery players based on Clotfelter, Cook (1991)[27]

| Amount bet by lottery players | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers drawn 14 April 1988 | Draw day | Days after draw | ||||

| April | Winner Numbers | 0 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 56 |

| 11 | 244 | 41 | 34 | 24 | 27 | 30 |

| 12 | 504 | 29 | 20 | 12 | 18 | 15 |

| 13 | 718 | 28 | 20 | 17 | 19 | 25 |

| 14 | 323 | 134 | 95 | 79 | 81 | 76 |

| 15 | 640 | 10 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 20 |

| 16 | 957 | 30 | 22 | 20 | 24 | 32 |

| Average percentage of players selecting previously

winning numbers compared to day of draw |

78% | 63% | 68% | 73% |

The effect of gambler’s fallacy can be observed as numbers are chosen far less frequently soon after they are selected as winners, recovering slowly over a two-month period. For example, on the 11th of April 1988, 41 players selected 244 as the winning combination. Three days later only 24 individuals selected 244, a 41.5% decrease. This is the gambler’s fallacy in motion, as lottery players believe that the occurrence of a winning combination in previous days will decrease its likelihood of occurring today.

Video game players[edit]

Several video games feature the use of loot boxes, a collection of in-game items awarded on opening with random contents set by rarity metrics, as a monetization scheme. Since around 2018, loot boxes have come under scrutiny from governments and advocates on the basis they are akin to gambling, particularly for games aimed at youth. Some games use a special «pity-timer» mechanism, that if the player has opened several loot boxes in a row without obtaining a high-rarity item, subsequent loot boxes will improve the odds of a higher-rate item drop. This is considered to feed into the gambler’s fallacy since it reinforces the idea that a player will eventually obtain a high-rarity item (a win) after only receiving common items from a string of previous loot boxes.[28]

See also[edit]

- Availability heuristic

- Gambler’s conceit

- Gambler’s ruin

- Inverse gambler’s fallacy

- Hot hand fallacy

- Law of averages

- Martingale (betting system)

- Mean reversion (finance)

- Memorylessness

- Oscar’s grind

- Regression toward the mean

- Statistical regularity

- Problem gambling

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Why we gamble like monkeys». BBC.com. 2015-01-02.

- ^ a b c d e Oppenheimer, D.M., & Monin, B. (2009). The retrospective gambler’s fallacy: Unlikely events, constructing the past, and multiple universes. Judgment and Decision Making, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 326-334

- ^ Leslie, J. (1989). Universes. London: Routledge.

- ^ Hacking, I (1987). «The inverse gambler’s fallacy: The argument from design. The anthropic principle applied to Wheeler universes». Mind. 96 (383): 331–340. doi:10.1093/mind/xcvi.383.331.

- ^ White, R (2000). «Fine-tuning and multiple universes». Noûs. 34 (2): 260–276. doi:10.1111/0029-4624.00210.

- ^ Barron, Greg; Leider, Stephen (13 October 2009). «The role of experience in the Gambler’s Fallacy» (PDF). Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-03-22.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1986). Entertaining Mathematical Puzzles. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-486-25211-7. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- ^ O’Neill, B.; Puza, B.D. (2004). «Dice have no memories but I do: A defence of the reverse gambler’s belief». Reprinted in abridged form as: O’Neill, B.; Puza, B.D. (2005). «In defence of the reverse gambler’s belief». The Mathematical Scientist. 30 (1): 13–16. ISSN 0312-3685.

- ^ a b c Tversky, Amos; Daniel Kahneman (1971). «Belief in the law of small numbers» (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 76 (2): 105–110. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.592.3838. doi:10.1037/h0031322. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-06.

- ^ a b Tversky, Amos; Daniel Kahneman (1974). «Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases». Science. 185 (4157): 1124–1131. Bibcode:1974Sci…185.1124T. doi:10.1126/science.185.4157.1124. PMID 17835457. S2CID 143452957. Archived from the original on 2018-06-01. Retrieved 2017-06-19.

- ^ Tune, G. S. (1964). «Response preferences: A review of some relevant literature». Psychological Bulletin. 61 (4): 286–302. doi:10.1037/h0048618. PMID 14140335.

- ^ Gilovich, Thomas (1991). How we know what isn’t so. New York: The Free Press. pp. 16–19. ISBN 978-0-02-911706-4.

- ^ Rogers, Paul (1998). «The cognitive psychology of lottery gambling: A theoretical review». Journal of Gambling Studies. 14 (2): 111–134. doi:10.1023/A:1023042708217. ISSN 1050-5350. PMID 12766438. S2CID 21141130.

- ^ a b Sundali, J.; Croson, R. (2006). «Biases in casino betting: The hot hand and the gambler’s fallacy». Judgment and Decision Making. 1: 1–12.

- ^ Keren, Gideon; Lewis, Charles (1994). «The Two Fallacies of Gamblers: Type I and Type II». Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 60 (1): 75–89. doi:10.1006/obhd.1994.1075. ISSN 0749-5978.

- ^ Oppenheimer, D. M.; Monin, B. (2009). «The retrospective gambler’s fallacy: Unlikely events, constructing the past, and multiple universes». Judgment and Decision Making. 4: 326–334.

- ^ Ayton, P.; Fischer, I. (2004). «The hot-hand fallacy and the gambler’s fallacy: Two faces of subjective randomness?». Memory and Cognition. 32 (8): 1369–1378. doi:10.3758/bf03206327. PMID 15900930.

- ^ Burns, Bruce D.; Corpus, Bryan (2004). «Randomness and inductions from streaks: «Gambler’s fallacy» versus «hot hand»«. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 11 (1): 179–184. doi:10.3758/BF03206480. ISSN 1069-9384. PMID 15117006.

- ^ Huber, J.; Kirchler, M.; Stockl, T. (2010). «The hot hand belief and the gambler’s fallacy in investment decisions under risk». Theory and Decision. 68 (4): 445–462. doi:10.1007/s11238-008-9106-2. S2CID 154661530.

- ^ Xue, G.; Lu, Z.; Levin, I. P.; Bechara, A. (2011). «An fMRI study of risk-taking following wins and losses: Implications for the gambler’s fallacy». Human Brain Mapping. 32 (2): 271–281. doi:10.1002/hbm.21015. PMC 3429350. PMID 21229615.

- ^ Beach, L. R.; Swensson, R. G. (1967). «Instructions about randomness and run dependency in two-choice learning». Journal of Experimental Psychology. 75 (2): 279–282. doi:10.1037/h0024979. PMID 6062970.

- ^ Fischbein, E.; Schnarch, D. (1997). «The evolution with age of probabilistic, intuitively based misconceptions». Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. 28 (1): 96–105. doi:10.2307/749665. JSTOR 749665.

- ^ Roney, C. J.; Trick, L. M. (2003). «Grouping and gambling: A gestalt approach to understanding the gambler’s fallacy». Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 57 (2): 69–75. doi:10.1037/h0087414. PMID 12822837.

- ^ a b Chen, Daniel; Moskowitz, Tobias J.; Shue, Kelly (2016-03-24). «Decision-Making Under the Gambler’s Fallacy: Evidence from Asylum Judges, Loan Officers, and Baseball Umpires*». The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 131 (3): 1181–1242. doi:10.1093/qje/qjw017. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ^ Cole, Shawn; Kanz, Martin; Kapper, Leora (2015). «Incentivizing Calculated Risk-Taking: Evidence from an Experiment with Commercial Bank Loan Officers». Journal of Finance. 70 (2): 537–575. doi:10.1111/jofi.12233.

- ^ a b Terrell, Dek (October 1994). «A test of the gambler’s fallacy: evidence from pari-mutuel games». Insurance: Mathematics and Economics. 15 (1): 83–84. doi:10.1016/0167-6687(94)90729-3. ISSN 0167-6687.

- ^ a b Clotfelter, Charles; Cook, Philip (1991). «The «Gambler’s Fallacy» in lottery play». National Bureau of Economic Research: 1–15.

- ^ Xiao, Leon Y.; Henderson, Laura L.; Yang, Yuhan; Newall, Philip W. S. (2021). «Gaming the System: Suboptimal Compliance with Loot Box Probability Disclosure Regulations in China». Behavioural Public Policy: 1–27. doi:10.1017/bpp.2021.23. S2CID 237672988.

The gambler’s fallacy, also known as the Monte Carlo fallacy or the fallacy of the maturity of chances, is the incorrect belief that, if a particular event occurs more frequently than normal during the past, it is less likely to happen in the future (or vice versa), when it has otherwise been established that the probability of such events does not depend on what has happened in the past. Such events, having the quality of historical independence, are referred to as statistically independent. The fallacy is commonly associated with gambling, where it may be believed, for example, that the next dice roll is more than usually likely to be six because there have recently been fewer than the expected number of sixes.

The term «Monte Carlo fallacy» originates from the best known example of the phenomenon, which occurred in the Monte Carlo Casino in 1913.[1]

Examples[edit]

Coin toss[edit]

Over time, the proportion of red/blue coin tosses approaches 50-50, but the difference does not systematically decrease to zero.

The gambler’s fallacy can be illustrated by considering the repeated toss of a fair coin. The outcomes in different tosses are statistically independent and the probability of getting heads on a single toss is 1/2 (one in two). The probability of getting two heads in two tosses is 1/4 (one in four) and the probability of getting three heads in three tosses is 1/8 (one in eight). In general, if Ai is the event where toss i of a fair coin comes up heads, then:

.

If after tossing four heads in a row, the next coin toss also came up heads, it would complete a run of five successive heads. Since the probability of a run of five successive heads is 1/32 (one in thirty-two), a person might believe that the next flip would be more likely to come up tails rather than heads again. This is incorrect and is an example of the gambler’s fallacy. The event «5 heads in a row» and the event «first 4 heads, then a tails» are equally likely, each having probability 1/32. Since the first four tosses turn up heads, the probability that the next toss is a head is:

.

While a run of five heads has a probability of 1/32 = 0.03125 (a little over 3%), the misunderstanding lies in not realizing that this is the case only before the first coin is tossed. After the first four tosses in this example, the results are no longer unknown, so their probabilities are at that point equal to 1 (100%). The probability of a run of coin tosses of any length continuing for one more toss is always 0.5. The reasoning that a fifth toss is more likely to be tails because the previous four tosses were heads, with a run of luck in the past influencing the odds in the future, forms the basis of the fallacy.

Why the probability is 1/2 for a fair coin[edit]

If a fair coin is flipped 21 times, the probability of 21 heads is 1 in 2,097,152. The probability of flipping a head after having already flipped 20 heads in a row is 1/2. Assuming a fair coin:

- The probability of 20 heads, then 1 tail is 0.520 × 0.5 = 0.521

- The probability of 20 heads, then 1 head is 0.520 × 0.5 = 0.521

The probability of getting 20 heads then 1 tail, and the probability of getting 20 heads then another head are both 1 in 2,097,152. When flipping a fair coin 21 times, the outcome is equally likely to be 21 heads as 20 heads and then 1 tail. These two outcomes are equally as likely as any of the other combinations that can be obtained from 21 flips of a coin. All of the 21-flip combinations will have probabilities equal to 0.521, or 1 in 2,097,152. Assuming that a change in the probability will occur as a result of the outcome of prior flips is incorrect because every outcome of a 21-flip sequence is as likely as the other outcomes. In accordance with Bayes’ theorem, the likely outcome of each flip is the probability of the fair coin, which is 1/2.

Other examples[edit]

The fallacy leads to the incorrect notion that previous failures will create an increased probability of success on subsequent attempts. For a fair 16-sided die, the probability of each outcome occurring is 1/16 (6.25%). If a win is defined as rolling a 1, the probability of a 1 occurring at least once in 16 rolls is:

The probability of a loss on the first roll is 15/16 (93.75%). According to the fallacy, the player should have a higher chance of winning after one loss has occurred. The probability of at least one win is now:

By losing one toss, the player’s probability of winning drops by two percentage points. With 5 losses and 11 rolls remaining, the probability of winning drops to around 0.5 (50%). The probability of at least one win does not increase after a series of losses; indeed, the probability of success actually decreases, because there are fewer trials left in which to win. The probability of winning will eventually be equal to the probability of winning a single toss, which is 1/16 (6.25%) and occurs when only one toss is left.

Reverse position[edit]

After a consistent tendency towards tails, a gambler may also decide that tails has become a more likely outcome. This is a rational and Bayesian conclusion, bearing in mind the possibility that the coin may not be fair; it is not a fallacy. Believing the odds to favor tails, the gambler sees no reason to change to heads. However it is a fallacy that a sequence of trials carries a memory of past results which tend to favor or disfavor future outcomes.

The inverse gambler’s fallacy described by Ian Hacking is a situation where a gambler entering a room and seeing a person rolling a double six on a pair of dice may erroneously conclude that the person must have been rolling the dice for quite a while, as they would be unlikely to get a double six on their first attempt.

Retrospective gambler’s fallacy[edit]

Researchers have examined whether a similar bias exists for inferences about unknown past events based upon known subsequent events, calling this the «retrospective gambler’s fallacy».[2]

An example of a retrospective gambler’s fallacy would be to observe multiple successive «heads» on a coin toss and conclude from this that the previously unknown flip was «tails».[2] Real world examples of retrospective gambler’s fallacy have been argued to exist in events such as the origin of the Universe. In his book Universes, John Leslie argues that «the presence of vastly many universes very different in their characters might be our best explanation for why at least one universe has a life-permitting character».[3] Daniel M. Oppenheimer and Benoît Monin argue that «In other words, the ‘best explanation’ for a low-probability event is that it is only one in a multiple of trials, which is the core intuition of the reverse gambler’s fallacy.»[2] Philosophical arguments are ongoing about whether such arguments are or are not a fallacy, arguing that the occurrence of our universe says nothing about the existence of other universes or trials of universes.[4][5] Three studies involving Stanford University students tested the existence of a retrospective gamblers’ fallacy. All three studies concluded that people have a gamblers’ fallacy retrospectively as well as to future events.[2] The authors of all three studies concluded their findings have significant «methodological implications» but may also have «important theoretical implications» that need investigation and research, saying «[a] thorough understanding of such reasoning processes requires that we not only examine how they influence our predictions of the future, but also our perceptions of the past.»[2]

Childbirth[edit]

In 1796, Pierre-Simon Laplace described in A Philosophical Essay on Probabilities the ways in which men calculated their probability of having sons: «I have seen men, ardently desirous of having a son, who could learn only with anxiety of the births of boys in the month when they expected to become fathers. Imagining that the ratio of these births to those of girls ought to be the same at the end of each month, they judged that the boys already born would render more probable the births next of girls.» The expectant fathers feared that if more sons were born in the surrounding community, then they themselves would be more likely to have a daughter. This essay by Laplace is regarded as one of the earliest descriptions of the fallacy.[6] Likewise, after having multiple children of the same sex, some parents may erroneously believe that they are due to have a child of the opposite sex.

Monte Carlo Casino[edit]

Perhaps the most famous example of the gambler’s fallacy occurred in a game of roulette at the Monte Carlo Casino on August 18, 1913, when the ball fell in black 26 times in a row. This was an extremely uncommon occurrence: the probability of a sequence of either red or black occurring 26 times in a row is (18/37)26-1 or around 1 in 66.6 million, assuming the mechanism is unbiased. Gamblers lost millions of francs betting against black, reasoning incorrectly that the streak was causing an imbalance in the randomness of the wheel, and that it had to be followed by a long streak of red.[1]

Non-examples[edit]

Non-independent events[edit]

The gambler’s fallacy does not apply when the probability of different events is not independent. In such cases, the probability of future events can change based on the outcome of past events, such as the statistical permutation of events. An example is when cards are drawn from a deck without replacement. If an ace is drawn from a deck and not reinserted, the next card drawn is less likely to be an ace and more likely to be of another rank. The probability of drawing another ace, assuming that it was the first card drawn and that there are no jokers, has decreased from 4/52 (7.69%) to 3/51 (5.88%), while the probability for each other rank has increased from 4/52 (7.69%) to 4/51 (7.84%). This effect allows card counting systems to work in games such as blackjack.

Bias[edit]

In most illustrations of the gambler’s fallacy and the reverse gambler’s fallacy, the trial (e.g. flipping a coin) is assumed to be fair. In practice, this assumption may not hold. For example, if a coin is flipped 21 times, the probability of 21 heads with a fair coin is 1 in 2,097,152. Since this probability is so small, if it happens, it may well be that the coin is somehow biased towards landing on heads, or that it is being controlled by hidden magnets, or similar.[7] In this case, the smart bet is «heads» because Bayesian inference from the empirical evidence — 21 heads in a row — suggests that the coin is likely to be biased toward heads. Bayesian inference can be used to show that when the long-run proportion of different outcomes is unknown but exchangeable (meaning that the random process from which the outcomes are generated may be biased but is equally likely to be biased in any direction) and that previous observations demonstrate the likely direction of the bias, the outcome which has occurred the most in the observed data is the most likely to occur again.[8]

For example, if the a priori probability of a biased coin is say 1%, and assuming that such a biased coin would come down heads say 60% of the time, then after 21 heads the probability of a biased coin has increased to about 32%.

The opening scene of the play Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead by Tom Stoppard discusses these issues as one man continually flips heads and the other considers various possible explanations.

Changing probabilities[edit]

If external factors are allowed to change the probability of the events, the gambler’s fallacy may not hold. For example, a change in the game rules might favour one player over the other, improving his or her win percentage. Similarly, an inexperienced player’s success may decrease after opposing teams learn about and play against their weaknesses. This is another example of bias.

Psychology[edit]

Origins[edit]

The gambler’s fallacy arises out of a belief in a law of small numbers, leading to the erroneous belief that small samples must be representative of the larger population. According to the fallacy, streaks must eventually even out in order to be representative.[9] Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman first proposed that the gambler’s fallacy is a cognitive bias produced by a psychological heuristic called the representativeness heuristic, which states that people evaluate the probability of a certain event by assessing how similar it is to events they have experienced before, and how similar the events surrounding those two processes are.[10][9] According to this view, «after observing a long run of red on the roulette wheel, for example, most people erroneously believe that black will result in a more representative sequence than the occurrence of an additional red»,[10] so people expect that a short run of random outcomes should share properties of a longer run, specifically in that deviations from average should balance out. When people are asked to make up a random-looking sequence of coin tosses, they tend to make sequences where the proportion of heads to tails stays closer to 0.5 in any short segment than would be predicted by chance, a phenomenon known as insensitivity to sample size.[11] Kahneman and Tversky interpret this to mean that people believe short sequences of random events should be representative of longer ones.[9] The representativeness heuristic is also cited behind the related phenomenon of the clustering illusion, according to which people see streaks of random events as being non-random when such streaks are actually much more likely to occur in small samples than people expect.[12]

The gambler’s fallacy can also be attributed to the mistaken belief that gambling, or even chance itself, is a fair process that can correct itself in the event of streaks, known as the just-world hypothesis.[13] Other researchers believe that belief in the fallacy may be the result of a mistaken belief in an internal locus of control. When a person believes that gambling outcomes are the result of their own skill, they may be more susceptible to the gambler’s fallacy because they reject the idea that chance could overcome skill or talent.[14]

Variations[edit]

Some researchers believe that it is possible to define two types of gambler’s fallacy: type one and type two. Type one is the classic gambler’s fallacy, where individuals believe that a particular outcome is due after a long streak of another outcome. Type two gambler’s fallacy, as defined by Gideon Keren and Charles Lewis, occurs when a gambler underestimates how many observations are needed to detect a favorable outcome, such as watching a roulette wheel for a length of time and then betting on the numbers that appear most often. For events with a high degree of randomness, detecting a bias that will lead to a favorable outcome takes an impractically large amount of time and is very difficult, if not impossible, to do.[15] The two types differ in that type one wrongly assumes that gambling conditions are fair and perfect, while type two assumes that the conditions are biased, and that this bias can be detected after a certain amount of time.

Another variety, known as the retrospective gambler’s fallacy, occurs when individuals judge that a seemingly rare event must come from a longer sequence than a more common event does. The belief that an imaginary sequence of die rolls is more than three times as long when a set of three sixes is observed as opposed to when there are only two sixes. This effect can be observed in isolated instances, or even sequentially. Another example would involve hearing that a teenager has unprotected sex and becomes pregnant on a given night, and concluding that she has been engaging in unprotected sex for longer than if we hear she had unprotected sex but did not become pregnant, when the probability of becoming pregnant as a result of each intercourse is independent of the amount of prior intercourse.[16]

Relationship to hot-hand fallacy[edit]

Another psychological perspective states that gambler’s fallacy can be seen as the counterpart to basketball’s hot-hand fallacy, in which people tend to predict the same outcome as the previous event — known as positive recency — resulting in a belief that a high scorer will continue to score. In the gambler’s fallacy, people predict the opposite outcome of the previous event — negative recency — believing that since the roulette wheel has landed on black on the previous six occasions, it is due to land on red the next. Ayton and Fischer have theorized that people display positive recency for the hot-hand fallacy because the fallacy deals with human performance, and that people do not believe that an inanimate object can become «hot.»[17] Human performance is not perceived as random, and people are more likely to continue streaks when they believe that the process generating the results is nonrandom.[18] When a person exhibits the gambler’s fallacy, they are more likely to exhibit the hot-hand fallacy as well, suggesting that one construct is responsible for the two fallacies.[14]

The difference between the two fallacies is also found in economic decision-making. A study by Huber, Kirchler, and Stockl in 2010 examined how the hot hand and the gambler’s fallacy are exhibited in the financial market. The researchers gave their participants a choice: they could either bet on the outcome of a series of coin tosses, use an expert opinion to sway their decision, or choose a risk-free alternative instead for a smaller financial reward. Participants turned to the expert opinion to make their decision 24% of the time based on their past experience of success, which exemplifies the hot-hand. If the expert was correct, 78% of the participants chose the expert’s opinion again, as opposed to 57% doing so when the expert was wrong. The participants also exhibited the gambler’s fallacy, with their selection of either heads or tails decreasing after noticing a streak of either outcome. This experiment helped bolster Ayton and Fischer’s theory that people put more faith in human performance than they do in seemingly random processes.[19]

Neurophysiology[edit]

While the representativeness heuristic and other cognitive biases are the most commonly cited cause of the gambler’s fallacy, research suggests that there may also be a neurological component. Functional magnetic resonance imaging has shown that after losing a bet or gamble, known as riskloss, the frontoparietal network of the brain is activated, resulting in more risk-taking behavior. In contrast, there is decreased activity in the amygdala, caudate, and ventral striatum after a riskloss. Activation in the amygdala is negatively correlated with gambler’s fallacy, so that the more activity exhibited in the amygdala, the less likely an individual is to fall prey to the gambler’s fallacy. These results suggest that gambler’s fallacy relies more on the prefrontal cortex, which is responsible for executive, goal-directed processes, and less on the brain areas that control affective decision-making.

The desire to continue gambling or betting is controlled by the striatum, which supports a choice-outcome contingency learning method. The striatum processes the errors in prediction and the behavior changes accordingly. After a win, the positive behavior is reinforced and after a loss, the behavior is conditioned to be avoided. In individuals exhibiting the gambler’s fallacy, this choice-outcome contingency method is impaired, and they continue to make risks after a series of losses.[20]

Possible solutions[edit]

The gambler’s fallacy is a deep-seated cognitive bias and can be very hard to overcome. Educating individuals about the nature of randomness has not always proven effective in reducing or eliminating any manifestation of the fallacy. Participants in a study by Beach and Swensson in 1967 were shown a shuffled deck of index cards with shapes on them, and were instructed to guess which shape would come next in a sequence. The experimental group of participants was informed about the nature and existence of the gambler’s fallacy, and were explicitly instructed not to rely on run dependency to make their guesses. The control group was not given this information. The response styles of the two groups were similar, indicating that the experimental group still based their choices on the length of the run sequence. This led to the conclusion that instructing individuals about randomness is not sufficient in lessening the gambler’s fallacy.[21]

An individual’s susceptibility to the gambler’s fallacy may decrease with age. A study by Fischbein and Schnarch in 1997 administered a questionnaire to five groups: students in grades 5, 7, 9, 11, and college students specializing in teaching mathematics. None of the participants had received any prior education regarding probability. The question asked was: «Ronni flipped a coin three times and in all cases heads came up. Ronni intends to flip the coin again. What is the chance of getting heads the fourth time?» The results indicated that as the students got older, the less likely they were to answer with «smaller than the chance of getting tails», which would indicate a negative recency effect. 35% of the 5th graders, 35% of the 7th graders, and 20% of the 9th graders exhibited the negative recency effect. Only 10% of the 11th graders answered this way, and none of the college students did. Fischbein and Schnarch theorized that an individual’s tendency to rely on the representativeness heuristic and other cognitive biases can be overcome with age.[22]

Another possible solution comes from Roney and Trick, Gestalt psychologists who suggest that the fallacy may be eliminated as a result of grouping. When a future event such as a coin toss is described as part of a sequence, no matter how arbitrarily, a person will automatically consider the event as it relates to the past events, resulting in the gambler’s fallacy. When a person considers every event as independent, the fallacy can be greatly reduced.[23]

Roney and Trick told participants in their experiment that they were betting on either two blocks of six coin tosses, or on two blocks of seven coin tosses. The fourth, fifth, and sixth tosses all had the same outcome, either three heads or three tails. The seventh toss was grouped with either the end of one block, or the beginning of the next block. Participants exhibited the strongest gambler’s fallacy when the seventh trial was part of the first block, directly after the sequence of three heads or tails. The researchers pointed out that the participants that did not show the gambler’s fallacy showed less confidence in their bets and bet fewer times than the participants who picked with the gambler’s fallacy. When the seventh trial was grouped with the second block, and was perceived as not being part of a streak, the gambler’s fallacy did not occur.

Roney and Trick argued that instead of teaching individuals about the nature of randomness, the fallacy could be avoided by training people to treat each event as if it is a beginning and not a continuation of previous events. They suggested that this would prevent people from gambling when they are losing, in the mistaken hope that their chances of winning are due to increase based on an interaction with previous events.

Users[edit]

Types of users[edit]

Within a real-world setting, numerous studies have uncovered that for various decision makers placed in high stakes scenarios, it is likely they will reflect some degree of strong negative autocorrelation in their judgement.

Asylum judges[edit]

In a study aimed at discovering if the negative autocorrelation that exists with the gambler’s fallacy existed in the decision made by U.S. asylum judges, results showed that after two successive asylum grants, a judge would be 5.5% less likely to approve a third grant.[24]

Baseball umpires[edit]

In the game of baseball, decisions are made every minute. One particular decision made by umpires which is often subject to scrutiny is the ‘strike zone’ decision. Whenever a batter does not swing, the umpire must decide if the ball was within a fair region for the batter, known as the strike zone. If outside of this zone, the ball does not count towards outing the batter. In a study of over 12,000 games, results showed that umpires are 1.3% less likely to call a strike if the previous two balls were also strikes.[24]

Loan officers[edit]

In the decision making of loan officers, it can be argued that monetary incentives are a key factor in biased decision making – making it hard to examine the gambler’s fallacy effect. However, research shows that loan officers who are not incentivised by monetary gain are 8% less likely to approve a loan if they approved one for the previous client.[25]

Lottery players[edit]

The effect of gambler’s fallacy on lottery selections, based on studies by Dek Terrell. After winning numbers are drawn, lottery players respond by reducing the number of times they select those numbers in following draws. This effect slowly corrects over time, as players become less affected by the fallacy.[26]

Lottery play and jackpots entice gamblers around the globe, with the biggest decision for hopeful winners being what numbers to pick. While most people will have their own strategy, evidence shows that after a number is selected as a winner in the current draw, the same number will experience a significant drop in selections in the following lottery. A popular study by Charles Clotfelter and Philip Cook, investigated this effect in 1991, where they concluded bettors would cease to select numbers immediately after they were selected — ultimately recovering selection popularity within three months.[27] Soon after, a 1994 study was constructed by Dek Terrell to test the findings of Clotfelter and Cook. The key change in Terrell’s study was the examination of a pari-mutuel lottery in which, a number selected with lower total wagers placed on it will result in a higher pay-out. While this examination did conclude that players in both types of lotteries exhibited behaviour in-line with the Gambler’s fallacy theory, those who took part in pari-mutuel betting seemed to be less influenced.[26]

[27]

| Amount bet by lottery players | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers drawn 14 April 1988 | Draw day | Days after draw | ||||

| April | Winner Numbers | 0 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 56 |

| 11 | 244 | 41 | 34 | 24 | 27 | 30 |

| 12 | 504 | 29 | 20 | 12 | 18 | 15 |

| 13 | 718 | 28 | 20 | 17 | 19 | 25 |

| 14 | 323 | 134 | 95 | 79 | 81 | 76 |

| 15 | 640 | 10 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 20 |

| 16 | 957 | 30 | 22 | 20 | 24 | 32 |

| Average percentage of players selecting previously

winning numbers compared to day of draw |

78% | 63% | 68% | 73% |

Table 1. Percentage change in numbers selected by lottery players based on Clotfelter, Cook (1991)

The effect of gambler’s fallacy can be observed as numbers are chosen far less frequently soon after they are selected as winners, recovering slowly over a two-month period. For example, on the 11th of April 1988, 41 players selected 244 as the winning combination. Three days later only 24 individuals selected 244, a 41.5% decrease. This is the gambler’s fallacy in motion, as lottery players believe that the occurrence of a winning combination in previous days will decrease its likelihood of occurring today.

Video game players[edit]

Several video games feature the use of loot boxes, a collection of in-game items awarded on opening with random contents set by rarity metrics, as a monetization scheme. Since around 2018, loot boxes have come under scrutiny from governments and advocates on the basis they are akin to gambling, particularly for games aimed at youth. Some games use a special «pity-timer» mechanism, that if the player has opened several loot boxes in a row without obtaining a high-rarity item, subsequent loot boxes will improve the odds of a higher-rate item drop. This is considered to feed into the gambler’s fallacy since it reinforces the idea that a player will eventually obtain a high-rarity item (a win) after only receiving common items from a string of previous loot boxes.[28]

See also[edit]

- Availability heuristic

- Gambler’s conceit

- Gambler’s ruin

- Inverse gambler’s fallacy

- Hot hand fallacy

- Law of averages

- Martingale (betting system)

- Mean reversion (finance)

- Memorylessness

- Oscar’s grind

- Regression toward the mean

- Statistical regularity

- Problem gambling

References[edit]

- ^ a b «Why we gamble like monkeys». BBC.com. 2015-01-02.

- ^ a b c d e Oppenheimer, D.M., & Monin, B. (2009). The retrospective gambler’s fallacy: Unlikely events, constructing the past, and multiple universes. Judgment and Decision Making, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 326-334

- ^ Leslie, J. (1989). Universes. London: Routledge.

- ^ Hacking, I (1987). «The inverse gambler’s fallacy: The argument from design. The anthropic principle applied to Wheeler universes». Mind. 96 (383): 331–340. doi:10.1093/mind/xcvi.383.331.

- ^ White, R (2000). «Fine-tuning and multiple universes». Noûs. 34 (2): 260–276. doi:10.1111/0029-4624.00210.

- ^ Barron, Greg; Leider, Stephen (13 October 2009). «The role of experience in the Gambler’s Fallacy» (PDF). Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-03-22.

- ^ Gardner, Martin (1986). Entertaining Mathematical Puzzles. Courier Dover Publications. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-486-25211-7. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- ^ O’Neill, B.; Puza, B.D. (2004). «Dice have no memories but I do: A defence of the reverse gambler’s belief». Reprinted in abridged form as: O’Neill, B.; Puza, B.D. (2005). «In defence of the reverse gambler’s belief». The Mathematical Scientist. 30 (1): 13–16. ISSN 0312-3685.

- ^ a b c Tversky, Amos; Daniel Kahneman (1971). «Belief in the law of small numbers» (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 76 (2): 105–110. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.592.3838. doi:10.1037/h0031322. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-07-06.