Время на прочтение

5 мин

Количество просмотров 44K

Когда в Linux сервер базы данных непредвиденно завершает работу, нужно найти причину. Причин может быть несколько. Например, SIGSEGV — сбой из-за бага в бэкенд-сервере. Но это редкость. Чаще всего просто заканчивается пространство на диске или память. Если закончилось пространство на диске, выход один — освободить место и перезапустить базу данных.

Out-Of-Memory Killer

Когда у сервера или процесса заканчивается память, Linux предлагает 2 пути решения: обрушить всю систему или завершить процесс (приложение), который съедает память. Лучше, конечно, завершить процесс и спасти ОС от аварийного завершения. В двух словах, Out-Of-Memory Killer — это процесс, который завершает приложение, чтобы спасти ядро от сбоя. Он жертвует приложением, чтобы сохранить работу ОС. Давайте сначала обсудим, как работает OOM и как его контролировать, а потом посмотрим, как OOM Killer решает, какое приложение завершить.

Одна из главных задач Linux — выделять память процессам, когда они ее просят. Обычно процесс или приложение запрашивают у ОС память, а сами используют ее не полностью. Если ОС будет выдавать память всем, кто ее просит, но не планирует использовать, очень скоро память закончится, и система откажет. Чтобы этого избежать, ОС резервирует память за процессом, но фактически не выдает ее. Память выделяется, только когда процесс действительно собирается ее использовать. Случается, что у ОС нет свободной памяти, но она закрепляет память за процессом, и когда процессу она нужна, ОС выделяет ее, если может. Минус в том, что иногда ОС резервирует память, но в нужный момент свободной памяти нет, и происходит сбой системы. OOM играет важную роль в этом сценарии и завершает процессы, чтобы уберечь ядро от паники. Когда принудительно завершается процесс PostgreSQL, в логе появляется сообщение:

Out of Memory: Killed process 12345 (postgres).Если в системе мало памяти и освободить ее невозможно, вызывается функция out_of_memory. На этом этапе ей остается только одно — завершить один или несколько процессов. OOM-killer должен завершать процесс сразу или можно подождать? Очевидно, что, когда вызывается out_of_memory, это связано с ожиданием операции ввода-вывода или подкачкой страницы на диск. Поэтому OOM-killer должен сначала выполнить проверки и на их основе решить, что нужно завершить процесс. Если все приведенные ниже проверки дадут положительный результат, OOM завершит процесс.

Выбор процесса

Когда заканчивается память, вызывается функция out_of_memory(). В ней есть функция select_bad_process(), которая получает оценку от функции badness(). Под раздачу попадет самый «плохой» процесс. Функция badness() выбирает процесс по определенным правилам.

- Ядру нужен какой-то минимум памяти для себя.

- Нужно освободить много памяти.

- Не нужно завершать процессы, которые используют мало памяти.

- Нужно завершить минимум процессов.

- Сложные алгоритмы, которые повышают шансы на завершение для тех процессов, которые пользователь сам хочет завершить.

Выполнив все эти проверки, OOM изучает оценку (oom_score). OOM назначает oom_score каждому процессу, а потом умножает это значение на объем памяти. У процессов с большими значениями больше шансов стать жертвами OOM Killer. Процессы, связанные с привилегированным пользователем, имеют более низкую оценку и меньше шансов на принудительное завершение.

postgres=# SELECT pg_backend_pid();

pg_backend_pid

----------------

3813

(1 row)Идентификатор процесса Postgres — 3813, поэтому в другой оболочке можно получить оценку, используя этот параметр ядра oom_score:

vagrant@vagrant:~$ sudo cat /proc/3813/oom_score

2Если вы совсем не хотите, чтобы OOM-Killer завершил процесс, есть еще один параметр ядра: oom_score_adj. Добавьте большое отрицательное значение, чтобы снизить шансы на завершение дорогого вам процесса.

sudo echo -100 > /proc/3813/oom_score_adjЧтобы задать значение oom_score_adj, установите OOMScoreAdjust в блоке сервиса:

[Service]

OOMScoreAdjust=-1000Или используйте oomprotect в команде rcctl.

rcctl set <i>servicename</i> oomprotect -1000Принудительное завершение процесса

Когда один или несколько процессов уже выбраны, OOM-Killer вызывает функцию oom_kill_task(). Эта функция отправляет процессу сигнал завершения. В случае нехватки памяти oom_kill() вызывает эту функцию, чтобы отправить процессу сигнал SIGKILL. В лог ядра записывается сообщение.

Out of Memory: Killed process [pid] [name].Как контролировать OOM-Killer

В Linux можно включать и отключать OOM-Killer (хотя последнее не рекомендуется). Для включения и отключения используйте параметр vm.oom-kill. Чтобы включить OOM-Killer в среде выполнения, выполните команду sysctl.

sudo -s sysctl -w vm.oom-kill = 1Чтобы отключить OOM-Killer, укажите значение 0 в этой же команде:

sudo -s sysctl -w vm.oom-kill = 0Результат этой команды сохранится не навсегда, а только до первой перезагрузки. Если нужно больше постоянства, добавьте эту строку в файл /etc/sysctl.conf:

echo vm.oom-kill = 1 >>/etc/sysctl.confЕще один способ включения и отключения — написать переменную panic_on_oom. Значение всегда можно проверить в /proc.

$ cat /proc/sys/vm/panic_on_oom

0Если установить значение 0, то когда закончится память, kernel panic не будет.

$ echo 0 > /proc/sys/vm/panic_on_oomЕсли установить значение 1, то когда закончится память, случится kernel panic.

echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/panic_on_oomOOM-Killer можно не только включать и выключать. Мы уже говорили, что Linux может зарезервировать для процессов больше памяти, чем есть, но не выделять ее по факту, и этим поведением управляет параметр ядра Linux. За это отвечает переменная vm.overcommit_memory.

Для нее можно указывать следующие значения:

0: ядро само решает, стоит ли резервировать слишком много памяти. Это значение по умолчанию в большинстве версий Linux.

1: ядро всегда будет резервировать лишнюю память. Это рискованно, ведь память может закончиться, потому что, скорее всего, однажды процессы затребуют положенное.

2: ядро не будет резервировать больше памяти, чем указано в параметре overcommit_ratio.

В этом параметре вы указываете процент памяти, для которого допустимо избыточное резервирование. Если для него нет места, память не выделяется, в резервировании будет отказано. Это самый безопасный вариант, рекомендованный для PostgreSQL. На OOM-Killer влияет еще один элемент — возможность подкачки, которой управляет переменная cat /proc/sys/vm/swappiness. Эти значения указывают ядру, как обрабатывать подкачку страниц. Чем больше значение, тем меньше вероятности, что OOM завершит процесс, но из-за операций ввода-вывода это негативно сказывается на базе данных. И наоборот — чем меньше значение, тем выше вероятность вмешательства OOM-Killer, но и производительность базы данных тоже выше. Значение по умолчанию 60, но если вся база данных помещается в память, лучше установить значение 1.

Итоги

Пусть вас не пугает «киллер» в OOM-Killer. В данном случае киллер будет спасителем вашей системы. Он «убивает» самые нехорошие процессы и спасает систему от аварийного завершения. Чтобы не приходилось использовать OOM-Killer для завершения PostgreSQL, установите для vm.overcommit_memory значение 2. Это не гарантирует, что OOM-Killer не придется вмешиваться, но снизит вероятность принудительного завершения процесса PostgreSQL.

Out-of-memory (OOM) errors take place when the Linux kernel can’t provide enough memory to run all of its user-space processes, causing at least one process to exit without warning. Without a comprehensive monitoring solution, OOM errors can be tricky to diagnose.

In this post, you will learn how to diagnose OOM errors in Linux kernels by:

- Analyzing different types of OOM error logs

- Choosing the most revealing metrics to explain low-memory situations on your hosts

- Using a profiler to understand memory-heavy processes

- Setting up automated alerts to troubleshoot OOM error messages more easily

Identify the error message

OOM error logs are normally available in your host’s syslog (in the file /var/log/syslog). In a dynamic environment with a large number of ephemeral hosts, it’s not realistic to comb through system logs manually—you should forward your logs to a monitoring platform for search and analysis. This way, you can configure your monitoring platform to parse these logs so you can query them and set automated alerts. Your monitoring platform should enrich your logs with metadata, including the host and application that produced them, so you can localize issues for further troubleshooting.

There are two major types of OOM error, and you should be prepared to identify each of these when diagnosing OOM issues:

- Error messages from user-space processes that handle OOM errors themselves

- Error messages from the kernel-space OOM Killer

Error messages from user-space processes

User-space processes receive access to system memory by making requests to the kernel, which returns a set of memory addresses (virtual memory) that the kernel will later assign to pages in physical RAM. When a user-space process first requests a virtual memory mapping, the kernel usually grants the request regardless of how many free pages are available. The kernel only allocates free pages to that mapping when it attempts to access memory with no corresponding page in RAM.

When an application fails to obtain a virtual memory mapping from the kernel, it will often handle the OOM error itself, emit a log message, then exit. If you know that certain hosts will be dedicated to memory-intensive processes, you should determine in advance what OOM logs these processes output, then set up alerts on these logs. Consider running game days to see what logs your system generates when it runs out of memory, and consult the documentation or source of your critical applications to ensure that your log management system can ingest and parse OOM logs.

The information you can obtain from error logs differs by application. For example, if a Go program attempts to request more memory than is available on the system, it will print a log that resembles the following, print a stack trace, then exit.

fatal error: runtime: out of memory

In this case, the log prints a detailed stack trace for each goroutine running at the time of the error, enabling you to figure out what the process was attempting to do before exiting. In this stack trace, we can see that our demo application was requesting memory while calling the *ImageProcessor.IdentifyImage() method.

goroutine 1 [running]: runtime.systemstack_switch() /usr/local/go/src/runtime/asm_amd64.s:330 fp=0xc0000b9d10 sp=0xc0000b9d08 pc=0x461570 runtime.mallocgc(0x278f3774, 0x695400, 0x1, 0xc00007e070) /usr/local/go/src/runtime/malloc.go:1046 +0x895 fp=0xc0000b9db0 sp=0xc0000b9d10 pc=0x40c575 runtime.makeslice(0x695400, 0x278f3774, 0x278f3774, 0x38) /usr/local/go/src/runtime/slice.go:49 +0x6c fp=0xc0000b9de0 sp=0xc0000b9db0 pc=0x44a9ec demo_app/imageproc.(*ImageProcessor).IdentifyImage(0xc00000c320, 0x278f3774, 0xc0278f3774) demo_app/imageproc/imageproc.go:36 +0xb5 fp=0xc0000b9e38 sp=0xc0000b9de0 pc=0x5163f5 demo_app/imageproc.(*ImageProcessor).IdentifyImage-fm(0x278f3774, 0x36710769) demo_app/imageproc/imageproc.go:34 +0x34 fp=0xc0000b9e60 sp=0xc0000b9e38 pc=0x5168b4 demo_app/imageproc.(*ImageProcessor).Activate(0xc00000c320, 0x36710769, 0xc000064f68, 0x1) demo_app/imageproc/imageproc.go:88 +0x169 fp=0xc0000b9ee8 sp=0xc0000b9e60 pc=0x516779 main.main() demo_app/main.go:39 +0x270 fp=0xc0000b9f88 sp=0xc0000b9ee8 pc=0x66cd50 runtime.main() /usr/local/go/src/runtime/proc.go:203 +0x212 fp=0xc0000b9fe0 sp=0xc0000b9f88 pc=0x435e72 runtime.goexit() /usr/local/go/src/runtime/asm_amd64.s:1373 +0x1 fp=0xc0000b9fe8 sp=0xc0000b9fe0 pc=0x463501

Since this behavior is baked into the Go runtime, Go-based infrastructure tools like Consul and Docker will output similar messages in low-memory conditions.

In addition to error messages from user-space processes, you’ll want to watch for OOM messages produced by the Linux kernel’s OOM Killer.

Error messages from the OOM Killer

If a Linux machine is seriously low on memory, the kernel invokes the OOM Killer to terminate a process. As with user-space OOM error logs, you should treat OOM Killer logs as indications of overall memory saturation.

How the OOM Killer works

To understand when the kernel produces OOM errors, it helps to know how the OOM Killer works. The OOM Killer terminates a process using heuristics. It assigns each process on your system an OOM score between 0 and 1000, based on its memory consumption as well as a user-configurable adjustment score. It then terminates the process with the highest score. This means that, by default, the OOM Killer may end up killing processes you don’t expect. (You will see different behavior if you configure the kernel to panic on OOM without invoking the OOM Killer, or to always kill the task that invoked the OOM Killer instead of assigning OOM scores.)

The kernel invokes the OOM Killer when it tries—but fails—to allocate free pages. When the kernel fails to retrieve a page from any memory zone in the system, it attempts to obtain free pages by other means, including memory compaction, direct reclaim, and searching again for free pages in case the OOM Killer had terminated a process during the initial search. If no free pages are available, the kernel triggers the OOM Killer. In other words, the kernel does not “see” that there are too few pages to satisfy a memory mapping until it is too late.

OOM Killer logs

You can use the OOM Killer logs both to identify which hosts in your system have run out of memory and to get detailed information on how much memory different processes were using at the time of the error. You can find an annotated example in the git commit that added this logging information to the Linux kernel. For example, the OOM Killer logs provide data on the system’s memory conditions at the time of the error.

Mem-Info: active_anon:895388 inactive_anon:43 isolated_anon:0 active_file:13 inactive_file:9 isolated_file:1 unevictable:0 dirty:0 writeback:0 unstable:0 slab_reclaimable:4352 slab_unreclaimable:7352 mapped:4 shmem:226 pagetables:3101 bounce:0 free:21196 free_pcp:150 free_cma:0

As you can see, the system had 21,196 pages of free memory when it threw the OOM error. With each page on the system holding up to 4 kB of memory, we can assume that the kernel needed to allocate at least 84.784 MB of physical memory to meet the requirements of currently running processes.

Understand the problem

If your monitoring platform has applied the appropriate metadata to your logs, you should be able to tell from a wave of OOM error messages which hosts are facing critically low memory conditions. The next step is to understand how frequently your hosts reach these conditions—and when memory utilization has spiked anomalously—by monitoring system memory metrics. In this section, we’ll review some key memory metrics and how to get more context around OOM errors.

Choose the right metrics

As we’ve seen, it’s difficult for the Linux kernel to determine when low-memory conditions will produce OOM errors. To make matters worse, the kernel is notoriously imprecise at measuring its own memory utilization, as a process can be allocated virtual memory but not actually use the physical RAM that those addresses map to. Since absolute measures of memory utilization can be unreliable, you should use another approach: determine what levels of memory utilization correlate with OOM errors in your hosts and what levels indicate a healthy baseline (e.g. by running game days).

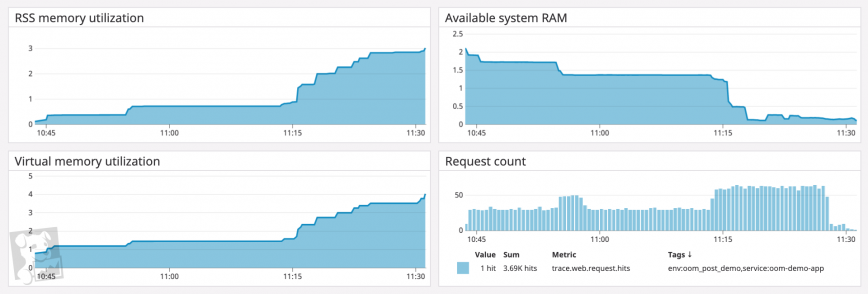

When monitoring overall memory utilization in relation to a healthy baseline, you should track both how much virtual memory the kernel has mapped for your processes and how much physical memory your processes are using (called the resident set size). If you’ve configured your system to use a significant amount of swap space—space on disk where the kernel stores inactive pages—you can also track this in order to monitor total memory utilization across your system.

Determine the scope

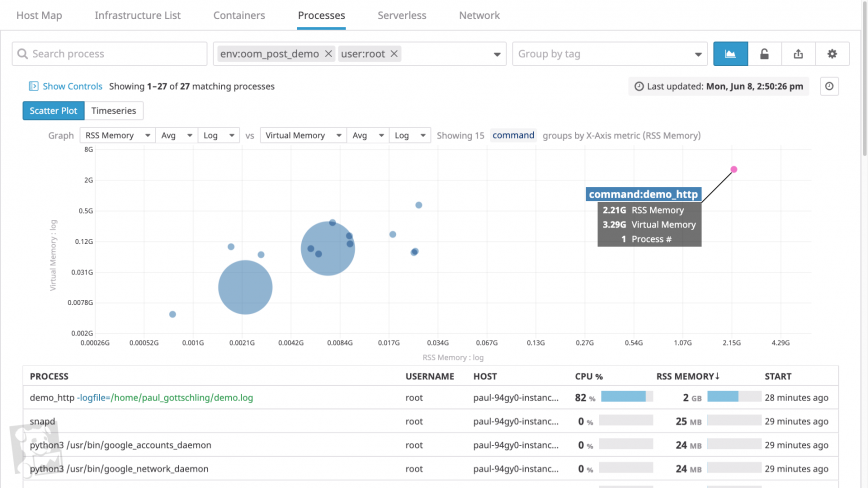

Your monitoring platform should tag your memory metrics with useful metadata about where those metrics came from—or at least the name of the associated host and process. The host tag is useful for determining if any one host is consuming an unusual amount of memory, whether in comparison to other hosts or to its baseline memory consumption.

You should also be able to group and filter your timeseries data either by process within a single host, or across all hosts in a cluster. This will help you determine whether any one process is using an unusual amount of memory. You’ll want to know which processes are running on each system and how long they’ve been running—in short, how recently your system has demanded an unsustainable amount of memory.

Find aggravating factors

If certain processes seem unusually memory-intensive, you’ll want to investigate them further by tracking metrics for other parts of your system that may be contributing to the issue.

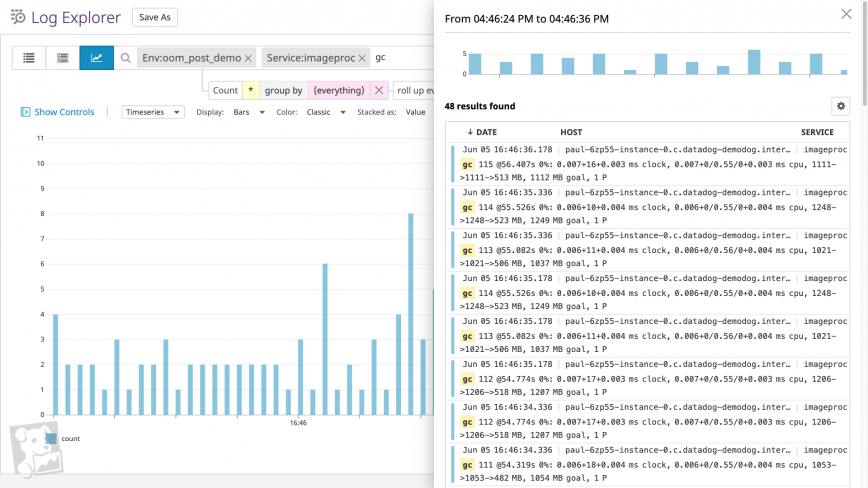

For processes with garbage-collected runtimes, you can investigate garbage collection as one source of higher-than-usual memory utilization. On a timeseries graph of heap memory utilization for a single process, garbage collection forms a sawtooth pattern (e.g. the JVM)—if the sawtooth does not return to a steady baseline, you likely have a memory leak. To see if your process’s runtime is garbage collecting as expected, graph the count of garbage collection events alongside heap memory usage.

Alternatively, you can search your logs for messages accompanying the “cliffs” of the sawtooth pattern. If you run a Go program with the GODEBUG environment variable assigned to gctrace=1, for example, the Go runtime will output a log every time it runs a garbage collection. (The screenshot below shows a graph of garbage collection log frequency over time, plus a typical list of garbage collection logs.)

Another factor has to do with the work that a process is performing. If an application is managing memory in a healthy way (i.e. without memory leaks) but still using more than expected, the application may be handling unusual levels of work. You’ll want to graph work metrics for memory-heavy applications, such as request rates for a web application, query throughput for a database, and so on.

Find unnecessary allocations

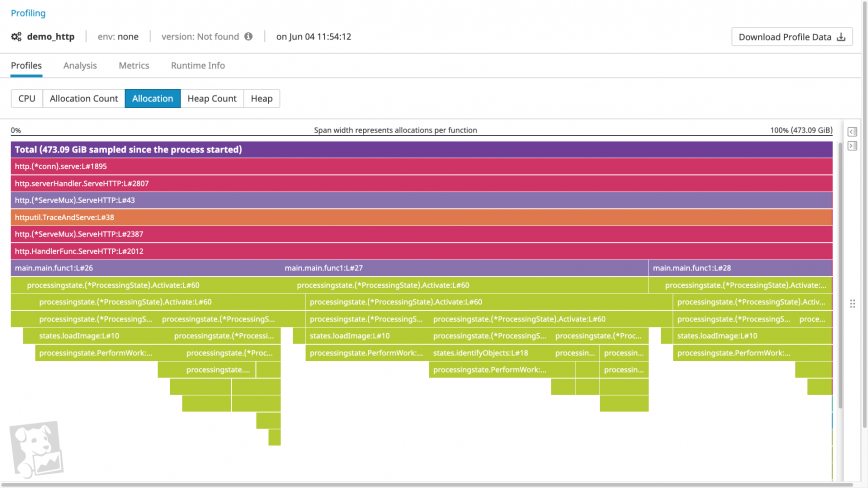

If a process doesn’t seem to be subject to any aggravating factors, it’s likely that the process is requesting more memory than you anticipate. One tool that helps you identify these memory requests is a memory profile.

Memory profiles visualize both the order of function calls within a call stack and how much heap memory each function call allocates. Using a memory profiler, you can quickly determine whether a given call is particularly memory intensive. And by examining the call’s parents and children, you can determine why a heavy allocation is taking place. For example, a profile could include a memory-intensive code path introduced by a recent feature release, suggesting that you should optimize the new code for memory utilization.

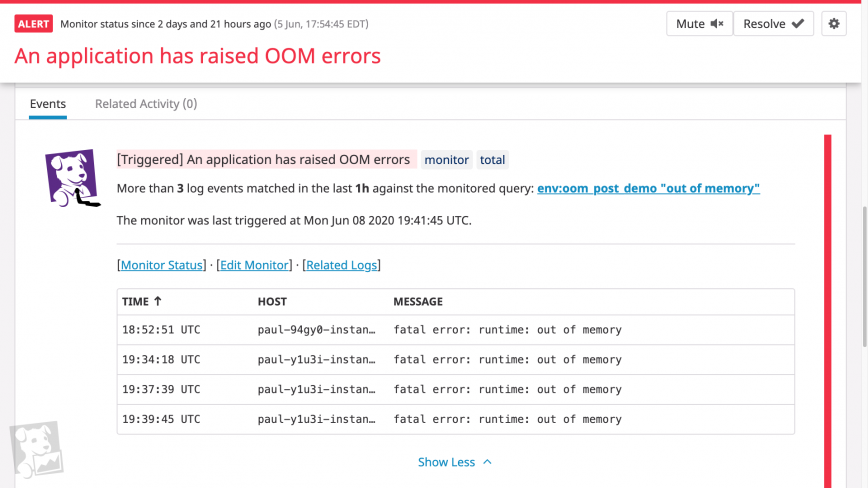

Get notified on OOM errors

The most direct way to find out about OOM errors is to set alerts on OOM log messages: whenever your system detects a certain number of OOM errors in a particular interval, your monitoring platform can alert your team. But to prevent OOM errors from impacting your system, you’ll want to be notified before OOM errors begin to terminate processes. Here again, knowing the healthy baseline usage of virtual memory and RSS utilization allows you to set alerts when memory utilization approaches unhealthy levels. Ideally, you should be using a monitoring platform that can forecast resource usage and alert your team based on expected trends, and flag anomalies in system metrics automatically.

Investigate OOM errors in a single platform

Since the Linux kernel provides an imprecise view of its own memory usage and relies on page allocation failures to raise OOM errors, you need to monitor a combination of OOM error logs, memory utilization metrics, and memory profiles.

A monitoring service like Datadog unifies all of these sources of data in a single platform, so you get comprehensive visibility into your system’s memory usage—whether at the level of the process or across every host in your environment. To stay on top of memory saturation issues, you can also set up alerts to automatically notify you about OOM logs or projected memory usage. By getting notified when OOM errors are likely, you’ll know which parts of your system you need to investigate to prevent application downtime. If you’re curious about using Datadog to monitor your infrastructure and applications, sign up for a free trial.

About Datadog

Datadog is a SaaS-based monitoring and analytics platform for cloud-scale infrastructure, applications, logs, and more. Datadog delivers complete visibility into the performance of modern applications in one place through its fully unified platform. By reducing the number of tools needed to troubleshoot performance problems, Datadog reduces the time needed to detect and resolve issues. With vendor-backed integrations for 400+ technologies, a world-class enterprise customer base, and focus on ease of use, Datadog is the leading choice for infrastructure and software engineering teams looking to improve cross-team collaboration, accelerate development cycles, and reduce operational and development costs.

Tags: devops, linux, memory, sysadmins

Check the System for Swap Information

Before we begin, we will take a look at our operating system to see if we already have some swap space available. We can have multiple swap files or swap partitions, but generally one should be enough.

We can see if the system has any configured swap by typing:

sudo swapon -s

Filename Type Size Used Priority

If you only get back the header of the table, as I’ve shown above, you do not currently have any swap space enabled.

Another, more familiar way of checking for swap space is with the free utility, which shows us system memory usage. We can see our current memory and swap usage in Megabytes by typing:

free -m

total used free shared buffers cached

Mem: 3953 154 3799 0 8 83

-/+ buffers/cache: 62 3890

Swap: 0 0 0

As you can see above, our total swap space in the system is «0». This matches what we saw with the previous command.

Check Available Space on the Hard Drive Partition

The typical way of allocating space for swap is to use a separate partition devoted to the task. However, altering the partitioning scheme is not always possible. We can just as easily create a swap file that resides on an existing partition.

Before we do this, we should be aware of our current disk usage. We can get this information by typing:

df -h

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/sda 70G 5.3G 64G 4% /

none 4.0K 0 4.0K 0% /sys/fs/cgroup

udev 2.0G 12K 2.0G 1% /dev

tmpfs 396M 312K 396M 1% /run

none 5.0M 0 5.0M 0% /run/lock

none 2.0G 0 2.0G 0% /run/shm

none 100M 0 100M 0% /run/user

As you can see on the first line, our hard drive partition has 70 Gigabytes available, so we have a huge amount of space to work with.

Although there are many opinions about the appropriate size of a swap space, it really depends on your personal preferences and your application requirements. Generally, an amount equal to or double the amount of RAM on your system is a good starting point.

Since our system has 8 Gigabytes of RAM, so we will create a swap space of 8 Gigabytes to match my system’s RAM.

Create a Swap File

Now that we know our available hard drive space, we can go about creating a swap file within our filesystem.

We will create a file called swapfile in our root (/) directory. The file must allocate the amount of space we want for our swap file. There are two main methods of doing this:

The Slower Method

Traditionally, we would create a file with preallocated space by using the dd command. This versatile disk utility writes from one location to another location.

We can use this to write zeros to the file from a special device in Linux systems located at /dev/zero that just spits out as many zeros as requested.

We specify the file size by using a combination of bs for block size and count for the number of blocks. What we assign to each parameter is almost entirely arbitrary. What matters is what the product of multiplying them turns out to be.

For instance, in our example, we’re looking to create a 4 Gigabyte file. We can do this by specifying a block size of 1 Gigabyte and a count of 4:

sudo dd if=/dev/zero of=/swapfile bs=1G count=8

8+0 records in

8+0 records out

8589934592 bytes (8.3 GB) copied, 18.6227 s, 231 MB/s

Check your command before pressing ENTER because this has the potential to destroy data if you point the of (which stands for output file) to the wrong location.

We can see that 8 Gigabytes have been allocated by typing:

ls -lh /swapfile

-rw-r—r— 1 root root 8.0G Nov 22 10:08 /swapfile

If you’ve completed the command above, you may notice that it took quite a while. In fact, you can see in the output that it took my system 36 seconds to create the file. That is because it has to write 8 Gigabytes of zeros to the disk.

If you want to learn how to create the file faster, remove the file and follow along below:

sudo rm /swapfile

The Faster Method

The quicker way of getting the same file is by using the fallocate program. This command creates a file of a preallocated size instantly, without actually having to write dummy contents.

We can create a 8 Gigabyte file by typing:

sudo fallocate -l 8G /swapfile

The prompt will be returned to you almost immediately. We can verify that the correct amount of space was reserved by typing:

ls -lh /swapfile

-rw-r—r— 1 root root 8.0G Nov 22 10:10 /swapfile

As you can see, our file is created with the correct amount of space set aside.

Enabling the Swap File

Right now, our file is created, but our system does not know that this is supposed to be used for swap. We need to tell our system to format this file as swap and then enable it.

Before we do that though, we need to adjust the permissions on our file so that it isn’t readable by anyone besides root. Allowing other users to read or write to this file would be a huge security risk. We can lock down the permissions by typing:

sudo chmod 600 /swapfile

Verify that the file has the correct permissions by typing:

ls -lh /swapfile

-rw——- 1 root root 8.0G Nov 22 10:11 /swapfile

As you can see, only the columns for the root user have the read and write flags enabled.

Now that our file is more secure, we can tell our system to set up the swap space by typing:

sudo mkswap /swapfile

Setting up swapspace version 1, size = 8388600 KiB

no label, UUID=e3f2e7cf-b0a9-4cd4-b9ab-814b8a7d6933

Our file is now ready to be used as a swap space. We can enable this by typing:

sudo swapon /swapfile

We can verify that the procedure was successful by checking whether our system reports swap space now:

sudo swapon -s

Filename Type Size Used Priority

/swapfile file 8388600 0 -1

We have a new swap file here. We can use the free utility again to corroborate our findings:

free -m

total used free shared buffers cached

Mem: 7906 202 7704 0 5 30

-/+ buffers/cache: 66 7446

Swap: 8190 0 8190

Our swap has been set up successfully and our operating system will begin to use it as necessary.

Make the Swap File Permanent

We have our swap file enabled, but when we reboot, the server will not automatically enable the file. We can change that though by modifying the fstab file.

Edit the file with root privileges in your text editor:

sudo nano /etc/fstab

At the bottom of the file, you need to add a line that will tell the operating system to automatically use the file you created:

/swapfile none swap sw 0 0

Save and close the file when you are finished.

Swap Settings

There are a few options that you can configure that will have an impact on your system’s performance when dealing with swap.

The swappiness parameter configures how often your system swaps data out of RAM to the swap space. This is a value between 0 and 100 that represents a percentage.

With values close to zero, the kernel will not swap data to the disk unless absolutely necessary. Remember, interactions with the swap file are «expensive» in that they take a lot longer than interactions with RAM and they can cause a significant reduction in performance. Telling the system not to rely on the swap much will generally make your system faster.

Values that are closer to 100 will try to put more data into swap in an effort to keep more RAM space free. Depending on your applications’ memory profile or what you are using your server for, this might be better in some cases.

We can see the current swappiness value by typing:

cat /proc/sys/vm/swappiness

60

For a Desktop, a swappiness setting of 60 is not a bad value. For a Server, we’d probably want to move it closer to 0.

We can set the swappiness to a different value by using the sysctl command.

For instance, to set the swappiness to 10, we could type:

sudo sysctl vm.swappiness=10

vm.swappiness = 10

This setting will persist until the next reboot. We can set this value automatically at restart by adding the line to our /etc/sysctl.conf file:

sudo nano /etc/sysctl.conf

At the bottom, you can add:

vm.swappiness=10

Save and close the file when you are finished.

Another related value that you might want to modify is the vfs_cache_pressure. This setting configures how much the system will choose to cache inode and dentry information over other data.

Basically, this is access data about the filesystem. This is generally very costly to look up and very frequently requested, so it’s an excellent thing for your system to cache. You can see the current value by querying the proc filesystem again:

cat /proc/sys/vm/vfs_cache_pressure

100

As it is currently configured, our system removes inode information from the cache too quickly. We can set this to a more conservative setting like 50 by typing:

sudo sysctl vm.vfs_cache_pressure=50

vm.vfs_cache_pressure = 50

Again, this is only valid for our current session. We can change that by adding it to our configuration file like we did with our swappiness setting:

sudo nano /etc/sysctl.conf

At the bottom, add the line that specifies your new value:

vm.vfs_cache_pressure = 50

Save and close the file when you are finished.

Conclusion

If you are running into OOM (out of memory) errors, or if you find that your system is unable to use the applications you need, the best solution is to optimize your application configurations or upgrade your server. Configuring swap space, however, can give you more flexibility and can help buy you time on a less powerful server.

I had the exact problem. I bough a new MSI laptop and installed 64GB of ram and I got «out of memory» when I selected the first item on the ubuntu boot menu.

I tried countless combinations of failures including what was describe in other posts on this site and other sites.

I determined that the problem is related to the boot program being a 32 bit program which allows a total of 4GB of memory space for the boot program to use. My laptop as an i7-12800hx processor with integrated graphics and an nvidia-3070ti.

I tried the same install usb drive on a PC with no integrated video card on the CPU and it worked fine. The PC it work on had a thread-ripper CPU with no integrated graphics and a geforce GTX 1080 pci-express graphics card.

To get the laptop to boot and install ubuntu 22.04.1, I had to go into my bios (right ctrl-shift, left alt-f2 to get to the advanced bios) and switch primary display to the PEG (PCI Express Graphics (nvidia rtx 3070ti)) and disable anything to do with the intel integrated graphics on the chip. Then I had to hook up a monitor with a lower resolution (1680×1050 ) (through a thunderbolt docking station) to get it to work. I tried with a 4K monitor but it did not sync up properly. Doing all of this prevented the mapping of shared memory to the graphics controller into the lower 4GB of ram.

After I did all of that, the installation worked. I could boot from the USB boot menu and install ubuntu 22.04. After the installation was complete, I had to switch my graphics back to normal in the bios.

This fix worked great for me. The installation was basically flawless and it did not involve creating new ramfs file systems or modifying grub. No software changes at all. It was simply disabling the integrated graphics in my bios for the install.

By the way, after about 30 failed attempts, I went and installed fedora 36 to see if it was related to ubuntu. Fedora installed fine the first time. I just could not get the drivers that I needed to use nvenc in ffmpeg and still have the system boot after loading drivers. It failed so I went back to trying to find the solution using ubuntu.

Also, I did leave the secure-boot disabled from one of my many earlier attempts. You will probably need to disable secure-boot functionality in your bios also. (See other posts on this topic for that)

I hope this post helps you solve your installation problem.

dave hansen

В этой статье рассматривается стратегия освобождения памяти в Linux и то, как системный администратор может этим управлять.

Из предыдущей статьи вы узнали что каждому процессу выделяется блок памяти (виртуальная память) и он эту память использует (физическая память). Суммарно физическая память состоит из оперативной памяти и подкачки (swap). Но подкачка может лишь хранить какие-то данные, которые не очень востребованы. Процессам же, чтобы избежать сильных тормозов, требуется работать с оперативной памятью.

При всём этом, суммарно, виртуальной памяти может быть выделено больше чем есть оперативной памяти. И может случится такое, что процессу нужна память, а взять её не откуда. В этом случае ядро может высвободить занятую память тремя способами:

- сбросить, по мнению ядра, самые ненужные данные из резидентной памяти в swap;

- сбросить некоторые файлы, которые хранятся в Page Cache, на диск;

- запустить специальный инструмент OOM Killer, который завершит самый ненужный и занимающий больше всего памяти процесс.

Есть несколько стратегий распределения памяти. Управлять этими стратегиями можно с помощью параметра sysctl – vm.overcommit_memory. Этот параметр может принимать значения 0, 1 или 2:

- vm.overcommit_memory = 2 – сумма виртуальной память всех процессов не будет превышать физическую память. При этом, каждому отдельному процессу будет выделено не больше vm.overcommit_ratio процентов от всей памяти.

- vm.overcommit_memory = 1 – виртуальной памяти может быть выделено больше чем есть физической. При этом, если приложение действительно попытается использовать эту память а физической памяти не хватит, то произойдет событие out of memory. По умолчанию, при событии out of memory, запустится OOM Killer и завершит какой-то процесс. При такой стратегии можно настроить еще некоторые параметры sysctl:

- vm.panic_on_oom = 1 – при out of memory будет происходить kernel.panic вместо запуска OOM Killer;

- kernel.panic = 10 — при kernel.panic через 10 секунд сервер пере-загрузится.

- vm.overcommit_memory = 0 – такая настройка используется по умолчанию. При этом ядро, с помощью специальных алгоритмов, само решает когда и сколько выделять памяти процессам.

Работа OOM Killer

OOM Killer – это компонент ядра Linux, призванный решать проблему недостатка памяти за счет убийства одного из существующих процессов по определённому алгоритму. В случае нехватки памяти (out of memory) он убивает процесс с помощью сигнала SIGKILL и не даёт ему корректно завершиться.

Алгоритм работы OOM Killer следующий. Все процессы, во время своей работы, накапливают специальные балы – oom_score. И при нехватке памяти OOM Killer убивает процесс с наивысшим oom_score. Посмотреть значение oom_score для процесса можно так – cat /proc/<pid>/oom_score, например:

$ cat /proc/1/oom_score 0 $ cat /proc/2383/oom_score 668

Как рассчитывается oom_score (взято от сюда):

- чем больше памяти занимает процесс, тем выше oom_score;

- чем больше у процесса дочерних процессов, тем выше oom_score;

- чем выше у процесса Nice, тем выше oom_score;

- чем раньше создан процесс, тем ниже oom_score;

- если процесс имеет прямой доступ к аппаратному обеспечению, то oom_score снижается;

- если процесс имеет root привилегии, то oom_score снижается.

Но значением oom_score можно управлять, чтобы например обезопасить некоторые процессы от OOM Killer. Для этого у процесса есть параметр oom_score_adj. Чем меньше у процесса oom_score_adj, тем меньше oom_score.

Вы можете задать параметр oom_score_adj для служб systemd, поправив файл юнита службы. Для этого в секции [Service] укажите параметр OOMScoreAdjust со значением от – 1000 до 1000. Если указать -1000, то OOM Killer никогда не убьёт процессы данной службы. А если указать 1000, то для OOM Killer процессы этой службы превратятся в главную цель.

Также, вы можете напрямую записать значение oom_score_adj для определённого процесса. Для этого нужно поправить файл /proc/<pid>/oom_score_adj.

$ cat /proc/2383/oom_score_adj 0 $ cat /proc/2383/oom_score 668 $ echo 20 | sudo tee /proc/2383/oom_score_adj $ cat /proc/2383/oom_score 682

В примере видно что вначале oom_score_adj для процесса 2383 равнялся 0, а oom_score равнялся 668. Затем я поменял значение oom_score_adj на 20 и oom_score увеличился до 682.

Итог

Вы узнали про некоторые параметры sysctl, с помощью которых можно настроить стратегию высвобождения памяти:

- vm.overcommit_memory – тип стратегии;

- vm.overcommit_ratio – процент всей памяти, который можно выделить одному процессу;

- vm.panic_on_oom – при событии out of memory выполнить kernel.panic;

- kernel.panic – перезагрузить сервер через указанное число секунд в случае kernel.panic.

Также вы узнали про инструмент OOM Killer. И про значения oom_score и oom_score_adj на которые полагается OOM Killer в своей работе.

И вы узнали что ситуация нехватки памяти называется – out of memory.

Сводка

Имя статьи

Стратегия освобождения памяти в Linux

Описание

В этой статье рассматривается стратегия освобождения памяти в Linux и то, как системный администратор может этим управлять

Like the title says, I need a PERMANENT solution for the «Out of memory» (OOM) Boot Error

PLEASE DON’T TELL ME THAT IT’S AN UPSTREAM BUG FROM UBUNTU.

I already know that.

I am looking for a permanent solution here, not a history lesson…

Also please try to give complete and easy to follow step by step (copy/paste) instructions.

I always do that when I try to help someone.

THANKS.

Also, I only use MATE Desktop, but I’m guessing this crap affects all «flavors», right?

I almost forgot to mention, both my PCs use the same Samsung 43 inch 4K UHD smart monitor…

OK, here’s what I got so far:

It is my understanding that this whole mess was somehow caused by Canonical, who for some stupid reason, decided to mess with Grub2, but please correct me if I’m wrong…

I guess some people have a complete disregard for the good old American saying:

IF IT AIN’T BROKE, DON’T FIX IT !!!

By the way, I can boot just fine from Live USB, thanks to VENTOY’s Secondary Menu, which includes 2 options:

— Boot in normal mode

— Boot in grub2 mode

But once installed to METAL, all goes to hell, I can no longer boot, and I get the…

Error: out of memory

Press any key to continue

Funny thing is that I can boot just fine on an older PC with a low end Gigabyte B85M-D2V mobo and a Core i5-4460 CPU.

No «out of memory» errors on that old machine…

Now with my Intel NUC9i7QNX Extreme Kit that has a Core i7-9750H CPU, it won’t boot, and I get this POS out of memory error. I even tried flashing the BIOS to the latest version, NO JOY…

I did the «e» during the posting on the Ventoy USB stick, and all I could see on Ventoy’s Grub2 Boot Option was this:

set gfxpayload=keep

I tried to apend my installed boot with that, so far unsuccessful…

Maybe one of y’all knows how to properly do that…

The only workaround I found so far is this:

I also installed EndeavourOS (Arch based) on the same NUC, and after enabling the OS-Prober and updating GRUB2, I have a Linux Mint 21 listing in Endeavour’s grub2 boot menu. And guess what??? LINUX MINT BOOTS JUST FINE…

No more «Out of memory» (OOM) Boot Error

Last edited by LockBot on Wed May 24, 2023 10:00 pm, edited 4 times in total.

Reason: Topic automatically closed 6 months after creation. New replies are no longer allowed.

What do I think about Window$??? Just take a look at my AVATAR…

Out-of-memory (OOM) errors take place when the Linux kernel can’t provide enough memory to run all of its user-space processes, causing at least one process to exit without warning. Without a comprehensive monitoring solution, OOM errors can be tricky to diagnose.

In this post, you will learn how to diagnose OOM errors in Linux kernels by:

- Analyzing different types of OOM error logs

- Choosing the most revealing metrics to explain low-memory situations on your hosts

- Using a profiler to understand memory-heavy processes

- Setting up automated alerts to troubleshoot OOM error messages more easily

Identify the error message

OOM error logs are normally available in your host’s syslog (in the file /var/log/syslog). In a dynamic environment with a large number of ephemeral hosts, it’s not realistic to comb through system logs manually—you should forward your logs to a monitoring platform for search and analysis. This way, you can configure your monitoring platform to parse these logs so you can query them and set automated alerts. Your monitoring platform should enrich your logs with metadata, including the host and application that produced them, so you can localize issues for further troubleshooting.

There are two major types of OOM error, and you should be prepared to identify each of these when diagnosing OOM issues:

- Error messages from user-space processes that handle OOM errors themselves

- Error messages from the kernel-space OOM Killer

Error messages from user-space processes

User-space processes receive access to system memory by making requests to the kernel, which returns a set of memory addresses (virtual memory) that the kernel will later assign to pages in physical RAM. When a user-space process first requests a virtual memory mapping, the kernel usually grants the request regardless of how many free pages are available. The kernel only allocates free pages to that mapping when it attempts to access memory with no corresponding page in RAM.

When an application fails to obtain a virtual memory mapping from the kernel, it will often handle the OOM error itself, emit a log message, then exit. If you know that certain hosts will be dedicated to memory-intensive processes, you should determine in advance what OOM logs these processes output, then set up alerts on these logs. Consider running game days to see what logs your system generates when it runs out of memory, and consult the documentation or source of your critical applications to ensure that your log management system can ingest and parse OOM logs.

The information you can obtain from error logs differs by application. For example, if a Go program attempts to request more memory than is available on the system, it will print a log that resembles the following, print a stack trace, then exit.

fatal error: runtime: out of memory

In this case, the log prints a detailed stack trace for each goroutine running at the time of the error, enabling you to figure out what the process was attempting to do before exiting. In this stack trace, we can see that our demo application was requesting memory while calling the *ImageProcessor.IdentifyImage() method.

goroutine 1 [running]: runtime.systemstack_switch() /usr/local/go/src/runtime/asm_amd64.s:330 fp=0xc0000b9d10 sp=0xc0000b9d08 pc=0x461570 runtime.mallocgc(0x278f3774, 0x695400, 0x1, 0xc00007e070) /usr/local/go/src/runtime/malloc.go:1046 +0x895 fp=0xc0000b9db0 sp=0xc0000b9d10 pc=0x40c575 runtime.makeslice(0x695400, 0x278f3774, 0x278f3774, 0x38) /usr/local/go/src/runtime/slice.go:49 +0x6c fp=0xc0000b9de0 sp=0xc0000b9db0 pc=0x44a9ec demo_app/imageproc.(*ImageProcessor).IdentifyImage(0xc00000c320, 0x278f3774, 0xc0278f3774) demo_app/imageproc/imageproc.go:36 +0xb5 fp=0xc0000b9e38 sp=0xc0000b9de0 pc=0x5163f5 demo_app/imageproc.(*ImageProcessor).IdentifyImage-fm(0x278f3774, 0x36710769) demo_app/imageproc/imageproc.go:34 +0x34 fp=0xc0000b9e60 sp=0xc0000b9e38 pc=0x5168b4 demo_app/imageproc.(*ImageProcessor).Activate(0xc00000c320, 0x36710769, 0xc000064f68, 0x1) demo_app/imageproc/imageproc.go:88 +0x169 fp=0xc0000b9ee8 sp=0xc0000b9e60 pc=0x516779 main.main() demo_app/main.go:39 +0x270 fp=0xc0000b9f88 sp=0xc0000b9ee8 pc=0x66cd50 runtime.main() /usr/local/go/src/runtime/proc.go:203 +0x212 fp=0xc0000b9fe0 sp=0xc0000b9f88 pc=0x435e72 runtime.goexit() /usr/local/go/src/runtime/asm_amd64.s:1373 +0x1 fp=0xc0000b9fe8 sp=0xc0000b9fe0 pc=0x463501

Since this behavior is baked into the Go runtime, Go-based infrastructure tools like Consul and Docker will output similar messages in low-memory conditions.

In addition to error messages from user-space processes, you’ll want to watch for OOM messages produced by the Linux kernel’s OOM Killer.

Error messages from the OOM Killer

If a Linux machine is seriously low on memory, the kernel invokes the OOM Killer to terminate a process. As with user-space OOM error logs, you should treat OOM Killer logs as indications of overall memory saturation.

How the OOM Killer works

To understand when the kernel produces OOM errors, it helps to know how the OOM Killer works. The OOM Killer terminates a process using heuristics. It assigns each process on your system an OOM score between 0 and 1000, based on its memory consumption as well as a user-configurable adjustment score. It then terminates the process with the highest score. This means that, by default, the OOM Killer may end up killing processes you don’t expect. (You will see different behavior if you configure the kernel to panic on OOM without invoking the OOM Killer, or to always kill the task that invoked the OOM Killer instead of assigning OOM scores.)

The kernel invokes the OOM Killer when it tries—but fails—to allocate free pages. When the kernel fails to retrieve a page from any memory zone in the system, it attempts to obtain free pages by other means, including memory compaction, direct reclaim, and searching again for free pages in case the OOM Killer had terminated a process during the initial search. If no free pages are available, the kernel triggers the OOM Killer. In other words, the kernel does not “see” that there are too few pages to satisfy a memory mapping until it is too late.

OOM Killer logs

You can use the OOM Killer logs both to identify which hosts in your system have run out of memory and to get detailed information on how much memory different processes were using at the time of the error. You can find an annotated example in the git commit that added this logging information to the Linux kernel. For example, the OOM Killer logs provide data on the system’s memory conditions at the time of the error.

Mem-Info: active_anon:895388 inactive_anon:43 isolated_anon:0 active_file:13 inactive_file:9 isolated_file:1 unevictable:0 dirty:0 writeback:0 unstable:0 slab_reclaimable:4352 slab_unreclaimable:7352 mapped:4 shmem:226 pagetables:3101 bounce:0 free:21196 free_pcp:150 free_cma:0

As you can see, the system had 21,196 pages of free memory when it threw the OOM error. With each page on the system holding up to 4 kB of memory, we can assume that the kernel needed to allocate at least 84.784 MB of physical memory to meet the requirements of currently running processes.

Understand the problem

If your monitoring platform has applied the appropriate metadata to your logs, you should be able to tell from a wave of OOM error messages which hosts are facing critically low memory conditions. The next step is to understand how frequently your hosts reach these conditions—and when memory utilization has spiked anomalously—by monitoring system memory metrics. In this section, we’ll review some key memory metrics and how to get more context around OOM errors.

Choose the right metrics

As we’ve seen, it’s difficult for the Linux kernel to determine when low-memory conditions will produce OOM errors. To make matters worse, the kernel is notoriously imprecise at measuring its own memory utilization, as a process can be allocated virtual memory but not actually use the physical RAM that those addresses map to. Since absolute measures of memory utilization can be unreliable, you should use another approach: determine what levels of memory utilization correlate with OOM errors in your hosts and what levels indicate a healthy baseline (e.g. by running game days).

When monitoring overall memory utilization in relation to a healthy baseline, you should track both how much virtual memory the kernel has mapped for your processes and how much physical memory your processes are using (called the resident set size). If you’ve configured your system to use a significant amount of swap space—space on disk where the kernel stores inactive pages—you can also track this in order to monitor total memory utilization across your system.

Determine the scope

Your monitoring platform should tag your memory metrics with useful metadata about where those metrics came from—or at least the name of the associated host and process. The host tag is useful for determining if any one host is consuming an unusual amount of memory, whether in comparison to other hosts or to its baseline memory consumption.

You should also be able to group and filter your timeseries data either by process within a single host, or across all hosts in a cluster. This will help you determine whether any one process is using an unusual amount of memory. You’ll want to know which processes are running on each system and how long they’ve been running—in short, how recently your system has demanded an unsustainable amount of memory.

Find aggravating factors

If certain processes seem unusually memory-intensive, you’ll want to investigate them further by tracking metrics for other parts of your system that may be contributing to the issue.

For processes with garbage-collected runtimes, you can investigate garbage collection as one source of higher-than-usual memory utilization. On a timeseries graph of heap memory utilization for a single process, garbage collection forms a sawtooth pattern (e.g. the JVM)—if the sawtooth does not return to a steady baseline, you likely have a memory leak. To see if your process’s runtime is garbage collecting as expected, graph the count of garbage collection events alongside heap memory usage.

Alternatively, you can search your logs for messages accompanying the “cliffs” of the sawtooth pattern. If you run a Go program with the GODEBUG environment variable assigned to gctrace=1, for example, the Go runtime will output a log every time it runs a garbage collection. (The screenshot below shows a graph of garbage collection log frequency over time, plus a typical list of garbage collection logs.)

Another factor has to do with the work that a process is performing. If an application is managing memory in a healthy way (i.e. without memory leaks) but still using more than expected, the application may be handling unusual levels of work. You’ll want to graph work metrics for memory-heavy applications, such as request rates for a web application, query throughput for a database, and so on.

Find unnecessary allocations

If a process doesn’t seem to be subject to any aggravating factors, it’s likely that the process is requesting more memory than you anticipate. One tool that helps you identify these memory requests is a memory profile.

Memory profiles visualize both the order of function calls within a call stack and how much heap memory each function call allocates. Using a memory profiler, you can quickly determine whether a given call is particularly memory intensive. And by examining the call’s parents and children, you can determine why a heavy allocation is taking place. For example, a profile could include a memory-intensive code path introduced by a recent feature release, suggesting that you should optimize the new code for memory utilization.

Get notified on OOM errors

The most direct way to find out about OOM errors is to set alerts on OOM log messages: whenever your system detects a certain number of OOM errors in a particular interval, your monitoring platform can alert your team. But to prevent OOM errors from impacting your system, you’ll want to be notified before OOM errors begin to terminate processes. Here again, knowing the healthy baseline usage of virtual memory and RSS utilization allows you to set alerts when memory utilization approaches unhealthy levels. Ideally, you should be using a monitoring platform that can forecast resource usage and alert your team based on expected trends, and flag anomalies in system metrics automatically.

Investigate OOM errors in a single platform

Since the Linux kernel provides an imprecise view of its own memory usage and relies on page allocation failures to raise OOM errors, you need to monitor a combination of OOM error logs, memory utilization metrics, and memory profiles.

A monitoring service like Datadog unifies all of these sources of data in a single platform, so you get comprehensive visibility into your system’s memory usage—whether at the level of the process or across every host in your environment. To stay on top of memory saturation issues, you can also set up alerts to automatically notify you about OOM logs or projected memory usage. By getting notified when OOM errors are likely, you’ll know which parts of your system you need to investigate to prevent application downtime. If you’re curious about using Datadog to monitor your infrastructure and applications, sign up for a free trial.

About Datadog

Datadog is a SaaS-based monitoring and analytics platform for cloud-scale infrastructure, applications, logs, and more. Datadog delivers complete visibility into the performance of modern applications in one place through its fully unified platform. By reducing the number of tools needed to troubleshoot performance problems, Datadog reduces the time needed to detect and resolve issues. With vendor-backed integrations for 400+ technologies, a world-class enterprise customer base, and focus on ease of use, Datadog is the leading choice for infrastructure and software engineering teams looking to improve cross-team collaboration, accelerate development cycles, and reduce operational and development costs.

Tags: devops, linux, memory, sysadmins

This post contains affiliate links. If you click through and make a purchase, I may receive a commission (at no additional cost to you). This helps support the blog and allows me to continue to make free content. Thank you for your support!

Since two weeks, my website was frequently crashing because the MySQL server stopped abruptly at random times of the day.

This issue started when I was on a holiday. My site was down for several hours. I configured crontab to start MySQL server when the service had stopped. This didn’t help.

I enabled query cache to reduce the load on the server. I use NGINX Fast CGI cache, APCu, and OpCache for my sites. Thus, I didn’t felt the need to install a caching plugin for my WordPress blog.

I reinstalled WordPress, changed DB structure of WordPress Database tables from MyISAM to INNODB, but the MySQL service was still crashing. I checked error logs and found that the MySQL server stopped each time the PHP executed the code in the wp-db.php file.

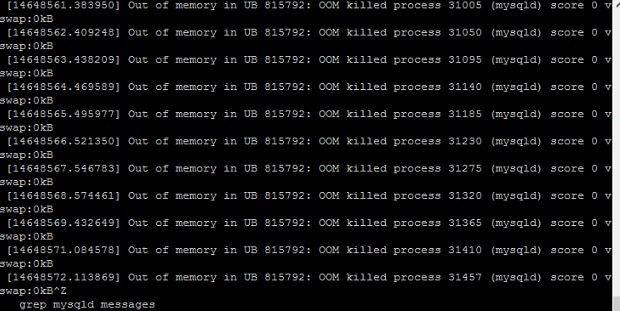

To seek help, I created a new thread on WordPress forum. One of the users asked me to check system log files (messages, Syslog) which can be found under the /var/log directory. The messages log file was populated with the below message:

out of memory in UB 815792: OOM killed process 29747 (MySQLD) error messages.

The out of memory manager module in my Linux VPS was killing the MySQL service immediately after the crontab started it.

OOM is a system module which ensures that aggressive processes using high system resources are killed to avoid malfunctioning of the system. In my case, the MySQLD service was using a large volume of RAM due to which the OOM killer had no other option than killing MySQLD process.

To fix the problem, I stopped MySQL server along with the services dependent on it. Then, I rebooted the VPS.

What should you do to prevent OOM process killer from stopping MySQL, PHP-FPM, NGINX, Apache, Oracle DB or any other critical service?

Check Linux memory usage often with commands like ps aux and free -mt. Once you find that the server doesn’t have enough free memory, identify the process which is using the most RAM and check its configuration. For example, if the PHP-FPM processes are using a large amount of RAM, you should tweak its configuration to lower the system memory usage.

Kill stopped jobs: When you stop a job in Linux, the task is still assigned resources the system had allocated to it. To free up these resources, you should terminate all finished jobs. To do so, run the below command in the terminal:

jobs -ps

Now, the terminal will display a list of process ids of stopped jobs. Use kill -9 pid command to kill them.

Check log files: If your website is deployed on a VPS server, you should check PHP, Nginx, MySQL as well as system log files every 2 or 3 hours. Use the command tail -30 file_name to learn about the latest errors.

Use updated software: When a developer or a company releases a new version of a product, the bugs that were found in earlier version of the software would have been fixed. If you’re using a CMS, make sure that the software you’re about to upgrade is compatible with your CMS.

If this doesn’t help, lower the max connections default value in my.cnf file to 50. Configure the PHP-FPM process manager to create additional processes ondemand and reduce the value of max children variable.

Conclusion: Fixing out of memory errors in Linux can be tricky. You should first find the cause of the problem by checking the error log files. If the problem is occurring because of poor code or slow SQL query, you should fix the code. If the code works great on other machines, reboot the OS.

В этой статье рассматривается стратегия освобождения памяти в Linux и то, как системный администратор может этим управлять.

Из предыдущей статьи вы узнали что каждому процессу выделяется блок памяти (виртуальная память) и он эту память использует (физическая память). Суммарно физическая память состоит из оперативной памяти и подкачки (swap). Но подкачка может лишь хранить какие-то данные, которые не очень востребованы. Процессам же, чтобы избежать сильных тормозов, требуется работать с оперативной памятью.

При всём этом, суммарно, виртуальной памяти может быть выделено больше чем есть оперативной памяти. И может случится такое, что процессу нужна память, а взять её не откуда. В этом случае ядро может высвободить занятую память тремя способами:

- сбросить, по мнению ядра, самые ненужные данные из резидентной памяти в swap;

- сбросить некоторые файлы, которые хранятся в Page Cache, на диск;

- запустить специальный инструмент OOM Killer, который завершит самый ненужный и занимающий больше всего памяти процесс.

Есть несколько стратегий распределения памяти. Управлять этими стратегиями можно с помощью параметра sysctl – vm.overcommit_memory. Этот параметр может принимать значения 0, 1 или 2:

- vm.overcommit_memory = 2 – сумма виртуальной память всех процессов не будет превышать физическую память. При этом, каждому отдельному процессу будет выделено не больше vm.overcommit_ratio процентов от всей памяти.

- vm.overcommit_memory = 1 – виртуальной памяти может быть выделено больше чем есть физической. При этом, если приложение действительно попытается использовать эту память а физической памяти не хватит, то произойдет событие out of memory. По умолчанию, при событии out of memory, запустится OOM Killer и завершит какой-то процесс. При такой стратегии можно настроить еще некоторые параметры sysctl:

- vm.panic_on_oom = 1 – при out of memory будет происходить kernel.panic вместо запуска OOM Killer;

- kernel.panic = 10 — при kernel.panic через 10 секунд сервер пере-загрузится.

- vm.overcommit_memory = 0 – такая настройка используется по умолчанию. При этом ядро, с помощью специальных алгоритмов, само решает когда и сколько выделять памяти процессам.

Работа OOM Killer

OOM Killer – это компонент ядра Linux, призванный решать проблему недостатка памяти за счет убийства одного из существующих процессов по определённому алгоритму. В случае нехватки памяти (out of memory) он убивает процесс с помощью сигнала SIGKILL и не даёт ему корректно завершиться.

Алгоритм работы OOM Killer следующий. Все процессы, во время своей работы, накапливают специальные балы – oom_score. И при нехватке памяти OOM Killer убивает процесс с наивысшим oom_score. Посмотреть значение oom_score для процесса можно так – cat /proc/<pid>/oom_score, например:

$ cat /proc/1/oom_score 0 $ cat /proc/2383/oom_score 668

Как рассчитывается oom_score (взято от сюда):

- чем больше памяти занимает процесс, тем выше oom_score;

- чем больше у процесса дочерних процессов, тем выше oom_score;

- чем выше у процесса Nice, тем выше oom_score;

- чем раньше создан процесс, тем ниже oom_score;

- если процесс имеет прямой доступ к аппаратному обеспечению, то oom_score снижается;

- если процесс имеет root привилегии, то oom_score снижается.

Но значением oom_score можно управлять, чтобы например обезопасить некоторые процессы от OOM Killer. Для этого у процесса есть параметр oom_score_adj. Чем меньше у процесса oom_score_adj, тем меньше oom_score.

Вы можете задать параметр oom_score_adj для служб systemd, поправив файл юнита службы. Для этого в секции [Service] укажите параметр OOMScoreAdjust со значением от – 1000 до 1000. Если указать -1000, то OOM Killer никогда не убьёт процессы данной службы. А если указать 1000, то для OOM Killer процессы этой службы превратятся в главную цель.

Также, вы можете напрямую записать значение oom_score_adj для определённого процесса. Для этого нужно поправить файл /proc/<pid>/oom_score_adj.

$ cat /proc/2383/oom_score_adj 0 $ cat /proc/2383/oom_score 668 $ echo 20 | sudo tee /proc/2383/oom_score_adj $ cat /proc/2383/oom_score 682

В примере видно что вначале oom_score_adj для процесса 2383 равнялся 0, а oom_score равнялся 668. Затем я поменял значение oom_score_adj на 20 и oom_score увеличился до 682.

Итог

Вы узнали про некоторые параметры sysctl, с помощью которых можно настроить стратегию высвобождения памяти:

- vm.overcommit_memory – тип стратегии;

- vm.overcommit_ratio – процент всей памяти, который можно выделить одному процессу;

- vm.panic_on_oom – при событии out of memory выполнить kernel.panic;

- kernel.panic – перезагрузить сервер через указанное число секунд в случае kernel.panic.

Также вы узнали про инструмент OOM Killer. И про значения oom_score и oom_score_adj на которые полагается OOM Killer в своей работе.

И вы узнали что ситуация нехватки памяти называется – out of memory.

Сводка

Имя статьи

Стратегия освобождения памяти в Linux

Описание

В этой статье рассматривается стратегия освобождения памяти в Linux и то, как системный администратор может этим управлять

Научиться настраивать MikroTik с нуля или систематизировать уже имеющиеся знания можно на углубленном курсе по администрированию MikroTik. Автор курса, сертифицированный тренер MikroTik Дмитрий Скоромнов, лично проверяет лабораторные работы и контролирует прогресс каждого своего студента. В три раза больше информации, чем в вендорской программе MTCNA, более 20 часов практики и доступ навсегда.

Начнем с начала, т.е. с выделения памяти в Linux. Любой запущенный процесс получает собственный выделенный участок памяти. Но этот участок не отображается на доступные физические адреса, а использует виртуальное адресное пространство, которое является дополнительным слоем абстракции между процессом и физической памятью. Для сопоставления адресов между виртуальной и физической памятью используются специальные структуры — таблицы страниц.

Что это дает? Во-первых, изоляцию процессов друг от друга, каждый из них работает в собственном виртуальном адресном пространстве и не имеет доступа к памяти других процессов. Во-вторых, позволяет системе гибко управлять физической памятью, например, для неактивного процесса часть страниц может быть перенесено из оперативной памяти в пространства подкачки, но это никак не повлияет на работу самого процесса, его адресное пространство не изменится, поменяется лишь трансляция в таблице страниц. И, наконец, это позволяет экономить физическую память, так если несколько процессов используют одни и те же данные, то система может транслировать адреса виртуальных пространств на один и тот же участок физической памяти.

Таким образом размер виртуальной памяти в системе теоретически ничем не ограничен и общий ее объем может существенно превышать имеющуюся в наличии физическую память. И в этом нет ничего плохого, например, мы запустили несколько графических приложений, для работы которым требуются библиотеки Qt или GTK, но нужно ли каждый раз загружать их в память? Нет, достаточно сделать это один раз, а затем просто транслировать адреса виртуальной памяти процессов на одни и те же участки физической памяти. Но при этом каждый процесс будет думать, что у него загружена собственная копия библиотек.

Поэтому современные Linux-системы выделяют память процессам с превышением имеющейся в наличии физической памяти (RAM + Swap), по умолчанию используя эвристические механизмы. Но случается, что процессы съедают всю доступную физическую память и вот тут системе надо выбрать что-то одно. А выбор, скажем честно, между плохим или очень плохим. Можно убить один из процессов и продолжить работать дальше, а можно вызвать Kernel panic. Понятно, что последнее — это совсем ни в какие ворота, поэтому на сцену выходит OOM Killer, это поведение используется в современных Linux системах по умолчанию.

Но кого же убьет OOM Killer? Бытует ошибочное мнение, что самый «толстый» процесс, занимающий самое большое количество памяти, однако это не так. Хотя заблуждения живучи, и народная молва рисует OOM Killer в виде ковбоя, врывающегося в переполненный салун и открывающий беспорядочную стрельбу по посетителям, преимущественно по толстым. Почему? Да попасть, наверное, проще…

На самом деле OOM Killer использует достаточно сложный анализ и присваивает каждому процессу очки негодности (badness) и при исчерпании памяти будет убит не кто-попало, а самый негодный процесс. Очки негодности могут принимать значения от -1000 до 1000, чем выше значение, тем более высока вероятность что OOM Killer убьет процесс. Процесс с -1000 очков никогда не будет убит OOM Killer.

Как вычисляются очки негодности? За основу берется процент физической памяти используемый процессом и умножается на 10, таким образом получаем базовое значение. Нетрудно заметить, что 1000 очков — это 100% использования памяти. Затем к данному значению начинают применяться различные модификаторы:

- Прибавляется половина очков всех дочерних процессов, имеющих собственную виртуальную память.

- Если приоритет процесса больше нуля очки умножаются на два. Приоритет может иметь значение от -20 (наивысший приоритет) до 20 (самый низкий).

- Очки делятся на коэффициент, связанный с процессорным временем, чем более активен процесс и чем больше процессорного времени он использует, тем больше будет этот коэффициент.

- Очки делятся на коэффициент, связанный с временем жизни процесса, чем больше времени прошло с момента запуска, тем выше будет это значение.

- Для процессов, запущенных от имени root, обслуживающих систему или процессов ввода-вывода очки делятся на 4.

- Для процесса, при выделении памяти которому произошла ошибка out of memory и процессам имеющим с ним общую память, очки делятся на 8.

- Очки умножаются на 2^oom_adj, где oom_adj — специальный коэффициент, имеющий значения от -17 до 15, при -17 процесс никогда не будет убить OOM Killer.

Если внимательно изучить эти критерии, то становится ясно, что OOM Killer убьет самый «толстый» процесс, который наименее активен в системе и имеет самое короткое время жизни. Согласитесь, это не тоже самое, что убить процесс с самым большим потреблением памяти. Такой подход позволяет достаточно эффективно бороться с утечкой памяти в кривых приложениях, минимизируя их влияние на систему.

Не так давно нам пришлось разбираться с ситуацией: в Linux Mint начал подвисать и падать браузер Chrome. Анализ ситуации выявил, что пользователь поставил стороннее расширение, которое приводило к утечке памяти и зависанию браузера, после чего на сцену выходил OOM Killer и убивал процесс. При этом параллельно были открыты процессы, которые потребляли больше памяти, чем утекало через Chrome, но OOM Killer их не трогал.

В системах виртуализации это будет неактивная виртуалка с наибольшим выделением памяти. Поэтому если у вас регулярно выключается одна из второстепенных машин — проверьте ситуацию с памятью, скорее всего это работа OOM Killer.

Как узнать количество очков, присвоенных процессу? Довольно просто, выполните команду:

cat /proc/PID/oom_scoreГде PID — идентификатор процесса. При необходимости мы можем изменить количество очков используя коэффициент oom_adj:

echo -17 > /proc/PID/oom_adjВ данном случае мы отправили процессу с указанным PID значение -17, т.е. обеспечили ему полную защиту от OOM Killer.

Все это имеет один большой недостаток: применить коэффициент oom_adj мы можем только к запущенному процессу и по факту это ручная работа. Не следует применять эти методы на практике, кроме, разве что диагностики и отладки.

В современных системах для управления службами используется systemd, который дает нам в руки простые и эффективные инструменты для управления очками негодности. Для этого в секцию [Service] юнита службы добавьте опцию:

[Service]

...

OOMScoreAdjust=-500

...Значение OOMScoreAdjust показывает насколько следует изменить количество очков процесса относительно рассчитанного количества, в нашем примере мы уменьшили его на 500. Таким образом мы можем защитить важные службы вашей системы от убийства со стороны OOM Killer, но не стоит злоупотреблять этой опцией, в критической ситуации будет лучше, если OOM Killer убьет даже важный процесс, но сохранит вам доступ к системе, нежели вы окажетесь в ситуации с полным исчерпанием физической памяти и недоступности или перезагрузки вашего сервера.

В любом случае, если вы столкнулись с работой OOM Killer, то следует тщательно проанализировать причины нехватки физической памяти и принять необходимые меры.

Надеемся, что после прочтения данной статьи OOM Killer перестанет быть для вас мифическим персонажем и вы будете понимать, что именно он делает, зачем и исходя из каких соображений. После чего он перестанет быть непредсказуемым черным ящиком, а станет вашим другом, помогающим сохранить работоспособность системы в критической ситуации нехватки ресурсов.

Научиться настраивать MikroTik с нуля или систематизировать уже имеющиеся знания можно на углубленном курсе по администрированию MikroTik. Автор курса, сертифицированный тренер MikroTik Дмитрий Скоромнов, лично проверяет лабораторные работы и контролирует прогресс каждого своего студента. В три раза больше информации, чем в вендорской программе MTCNA, более 20 часов практики и доступ навсегда.

Я уверен, что каждый пользователь в своей жизни хоть раз сталкивался с явлением переполнения оперативной памяти или OOM (Out Of Memory). Все помнят как это происходит: система встаёт раком колом, ядро начинает грузить свопом жёсткий диск на 100%, хорошо если можно хоть курсором двигать, хотя это уже делу не поможет. В этом случае помогает только перезагрузка. А ведь мы же только Libre Office с Chromium на 2 ГБ ОЗУ запустили! Не понятно, почему ядро Linux так плохо справляется с переполнением оперативки, но с этим явлением можно успешно бороться своими силами и при минимуме накладных затрат.

В борьбе с явлением OOM нам поможет Nohang — демон для GNU/Linux, предотвращающий наступление явления переполнения оперативной памяти устройства путём принудительного завершения «прожорливого» процесса.

Принцип работы

Nohang в виде демона постоянно находится в оперативной памяти устройства (потребляет ~10 Мб ОЗУ) и следит за свободным количеством оперативной памяти и своп-раздела. Как только наступает условие явной нехватки ОЗУ и свопа (эти параметры указываются в конфигурационном файле приложения) Nohang принудительно завершает «жирное» приложение, вызвавшее нехватку оперативной памяти устройства.

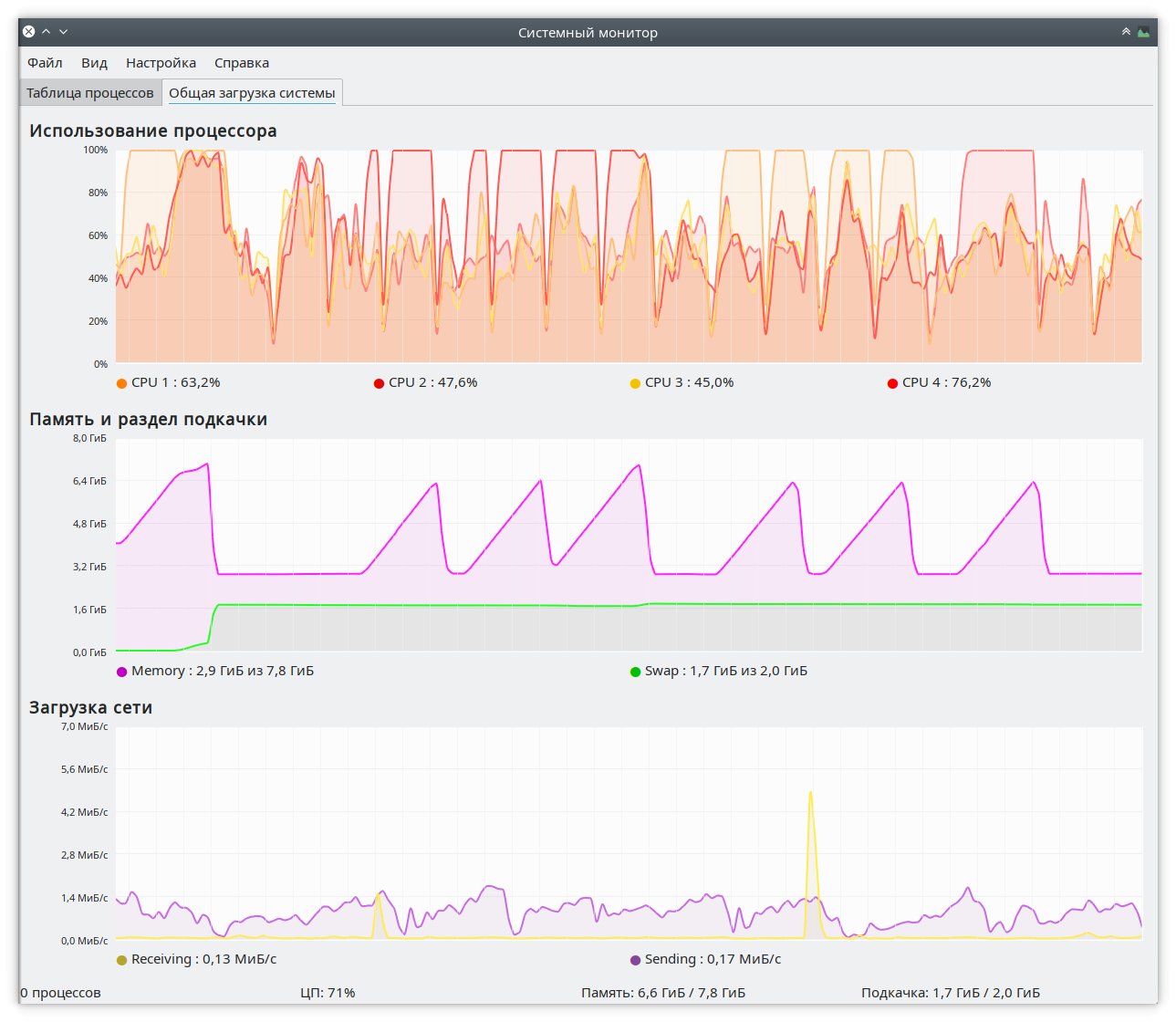

В качестве примера — скриншот окна монитора ресурсов KDE, на котором отображена работа демона Nohang.

На среднем графике видны факты наступления состояния OOM (переполнения памяти) ОЗУ компьютера, на котором производился эксперимент. Оперативная память накачивалась бесполезными пустыми данными с помощью команды:

Осторожно! Выполнение данной команды может привести (и без установленных утилит вроде Nohang — 100% приведёт) к переполнению оперативной памяти устройства и его зависанию, сколько бы ОЗУ в нём не было установлено!

Как видно, после первой попытки своп заполнился на 100% (в качестве свопа использовался раздел zRam) так же, как и ОЗУ, после чего Nohang прибивает процесс tail и оперативная память снова освобождается, возвращаясь к значению свободного места, которое имела до начала эксперимента. Интересно то, что своп остаётся заполненным практически на 100%, но при следующих попытках исчерпать всю доступную ОЗУ это не приводит к зависанию всей системы, и Nohang снова завершает прожорливый процесс tail, освобождаю ОЗУ. По субъективным ощущениям для пользователя, происходит кратковременное подтормаживание системы на пару секунд, после чего контроль над системой возвращается без каких-либо проблем. В общем — сказка!

Установка Nohang в различных дистрибутивах Linux

Так как не все, как я, используют в своей работе Arch Linux, рассмотрим процесс установки Nohang для всех самых популярных дистрибутивов.

Arch Linux, Manjaro Linux

pacaur -S nohang-git

sudo systemctl enable --now nohangDebian GNU/Linux, Ubuntu, Linux Mint

Устанавливаем из Github:

git clone https://github.com/hakavlad/nohang.git

cd nohang

sudo make install-desktop

sudo make systemdЕсли уведомления на рабочем столе не нужны, заменяем «sudo make install-desktop» на «sudo make install»

Fedora, RHEL, openSUSE

sudo dnf copr enable atim/nohang

sudo dnf install nohang

sudo systemctl enable --now nohangНастройка

Все параметры Nohang настраиваются в конфигурационном файле

/etc/nohang/nohang.confВ принципе, всё можно оставить как есть, параметры по-умолчанию там оптимальны для любой конфигурации железа.

Включение оповещений на рабочем столе

Чтобы включить всплывающие оповещения о нехватке ОЗУ и завершении приложений Nohang, нужно в файле конфигурации изменить следующие параметры на значение «True» чтобы получилось вот так:

post_action_gui_notifications = True

low_memory_warnings_enabled = TrueПосле чего сохранить изменения в конфигурационном файле и перезапустить Nohang для применения новой конфигурации:

sudo systemctl restart nohang.serviceПроверка

Проверяем состояние демона Nohang:

sudo systemctl status nohang.serviceСтатус работы должен быть указан зелёным цветом:

Active: active (running)Если так — Nohang запущен и работает нормально, можно приступать к экспериментам.

Сохраняем все несохранённые данные во всех приложениях, делаем резервные копии важных данных!

Это я на всякий случай 😏 Что ж, инициируем процесс накачки оперативной памяти пустыми данными:

И смотрим что из этого получится 😀 По идее, вы можете почувтвовать непродолжительный дискомфорт, проявляющийся в зависании системы на несколько секунд, после чего Nohang должен отработать по tail и управление системы вернётся в ваши руки. А точнее, скорее всего так и произойдёт, что можно будет считать успешным достижением поставленной цели.

Так же можно установить более легковесный менеджер OOM — Earlyoom.